By Brian Brennan – Photography By Michael Christensen

In my conversation with Howard “Mike” Michels from Stockton, California, he shares a fascinating story about how his lifelong dream transformed into the 1932 Ford Tudor sedan you see before you. It all started back in those high school days. As a freshman, filled with dreams, I purchased my first car: a 1949 Ford convertible, a 5-year-old beauty that set me back just $125. To afford that purchase, I saved every penny from my work on the farm driving tractors, irrigating fields, and dealing with the inevitable muck that comes with barn duties. Each dollar felt like a hard-fought victory, and he felt like he could conquer the world behind the wheel.

While visiting a friend on a sunny afternoon, Mike stumbled upon another 1932 Tudor—a dark primer beauty that seemed to whisper secrets from its past. As he stood close, it softly murmured one word: “ARDUN,” and at that moment, it was love at first sight. He struck a deal and brought it home against all better judgment, filled with excitement yet coming down from the high of that initial rush. The project was a deeply layered endeavor with its fair share of challenges. Mike faced nagging health issues, juggling six other car projects, and mourning the loss of his skilled upholstery man. However, he approached it all with quiet resolve, knowing this was an odyssey of passion.

Mike started with the frame—ASC framerails that would act as the backbone of the build. The foundation was laid precisely under the skilled hands of Squeak Bell from The Kiwi Konnection. The front and rear crossmembers were installed, and he made the decision to lengthen the frame by 2 inches at the firewall. By “Z” cutting the frame to leave the top rail in place for the body mount holes, the bottom portion slid forward 2 inches to maintain the reveal in relation to the future fenders. The gap was filled with a section of frame donated by Jon Hall. Mike completed the boxing and installed a CE center X-member, converting it into a large K-member for a fully powdercoated frame. The rear spreader bar is a solid steel shaft salvaged from an old ring roller. He then welded all the necessary brackets and mounts, including a TCI sway bar. The front axle is an original 1932, lowered by Industrial Chassis. He drilled the holes, tapered them at the outer ends, and sent them out for chroming. Next, he employed split 1932 wishbones, a Durant monoleaf spring, Aldan tube shocks, Borgeson-Vega cross steering, and Lincoln/Buick brakes to finish the front suspension. Ted Ingersoll bent the chromoly tie rod and draglink. Super Bell discs have replaced the Lincoln brakes and a Speedway 1-inch bore master cylinder.

The rear featured a Halibrand V-8 quick-change paired with a Truetrac differential, 3.78 gear, enhanced by the robust grip of Moser 31-spline axles and the sleek touch of Buick-finned aluminum brakes. Aldan coilovers completed the rear setup. Moving ahead, the front axle—a historical piece from 1932—was skillfully dropped by Industrial Chassis. The wheels are Halibrand Smoothies, 15×7 in the rear, and American Rebel Gassers, 15×5.5 in the front to match the smooth lip of the rears. Tires are BFGoodrich P255/70R15 and P155/80R15.

But then came the body. Mike still remembers his dread as sandblasting revealed a horror he could barely believe. The bottom 6 inches of the body were crumbled by rust, a dire reminder that beauty can often be skin deep. Don Brazil stepped in at that point, skillfully running the repairs using Brookville Roadster Subrails as a starting point, welding patch panels, and even fabricating new components when necessary. When he returned the restored sections, a simple note read, “Some assembly required,” burying the reality of what lay ahead under a layer of irony.

Guy Rouchenet then took over, adjusted all the margins, extended the front fenders to fit the frame due to the frame’s lengthening, bobbed the rears, and aligned the bottoms of the fenders with the running boards. He crafted the sleek front framehorn covers and the rear license plate box from this point. Next, he rolled the edges of the opening in the side panels of the Rootlieb-fabricated hood to accommodate the ARDUN valve covers. Larry Westervelt punched the 2-inch louvers in the top hood and interior kick panels. Dan Fink double-opening hinges were used.

The wheels came from Halibrand and American Rebel, while Mike’s upholsterer, Leon Jones, carefully designed the interior plan. Mike began to envision the culmination of all his efforts. Tragically, the journey took a turn when Jones died, causing Mike to set the project aside and dim his passion. Yet, the spark would return as he resumed his search for a new trimmer. Working alongside his wife, they immersed themselves in car shows, examining upholstery jobs and meeting talented craftsmen. After a year of tireless exploration, they discovered Louis Rojas in Stockton whose vision matched Mike’s. The seating features a pair of GM power buckets from a 1990s pickup, covered in Oxblood leather with Navy inserts. The rear bench is a custom-made seat, also covered in Oxblood leather.

One sunny afternoon, we began the painstaking transformation process. Mike had already created a one-piece headliner shell, although it was a tricky fit that required two pieces instead and was covered in Oxblood colored vinyl. Ron Mangus, another upholstery master, would wrap the 1949 Ford banjo-style steering wheel in luxurious navy blue leather while addressing the wiring and finishing touches. The original ashtrays and sunvisors returned to the vehicle, each honoring the history he cherished.

Mike replaced all the interior wood with a kit from Bogus Bob. Unfortunately, it didn’t fit properly, which was frustrating and required many adjustments. Bob Pundt donated the correct door latch mechanism. Pundt and Mike bought a pair of reproduction running boards from a limited production run. The top features 1-inch Styrofoam bats placed between the bows for insulation, topped with 1/8-inch plywood molded to create the compound curve of the top. On top of this is a custom-cut one-piece Koolmat, followed by 1/8-inch closed-cell foam, and finally, the original-style vinyl top. Mike shaped the reproduction tack strips using a buck he had made for his five-window. The radio and Sirius antennas are concealed beneath the top. The entire body is sound-deadened with Dynamat and insulated with Koolmat.

The electrical system’s complexity was my next puzzle to solve. An original 1932 locking ignition switch added a nostalgic touch, while the Centech panel and relays brought the car into the 21st century. With the clever placement of components in hidden spaces, Mike achieved a clean aesthetic without sacrificing function. The lighting—Sylvania performance headlights housed in nostalgic King Bee buckets—paired beautifully with Harley-Davidson “Tombstone” taillights.

Mike embraced technology by integrating a sound system that felt nearly futuristic, powered by a 600-watt amplifier. With the Pioneer head unit at the helm—offering Sirius radio, CD access, Bluetooth, and subwoofers tucked into the rear seat riser—he created a space that blended nostalgia with modern comfort. Old Air provided heat and A/C, ensuring that style came with comfort. The original dashboard features Classic Instruments electric and Stewart-Warner mechanical gauges. Other interior features include cruise control, an alarm, electric wipers, and a power cowl vent. Polished stainless fasteners gleamed throughout, each a testament to the labor of love involved.

Mike was enveloped in a cocoon of creativity as the car began to take shape, harmonizing the old with the new. The Midnight Blue paint was applied using PPG’s Shop Line basecoat/clearcoat. Mike upgraded his painting equipment to a 3M Accuspray system to achieve the smoothest finish possible. Herb Martinez laid down the stripes; also note the valve covers. With a hint of pride, he shares the story that he painted it all in his barn, pouring his heart and sweat into each stroke.

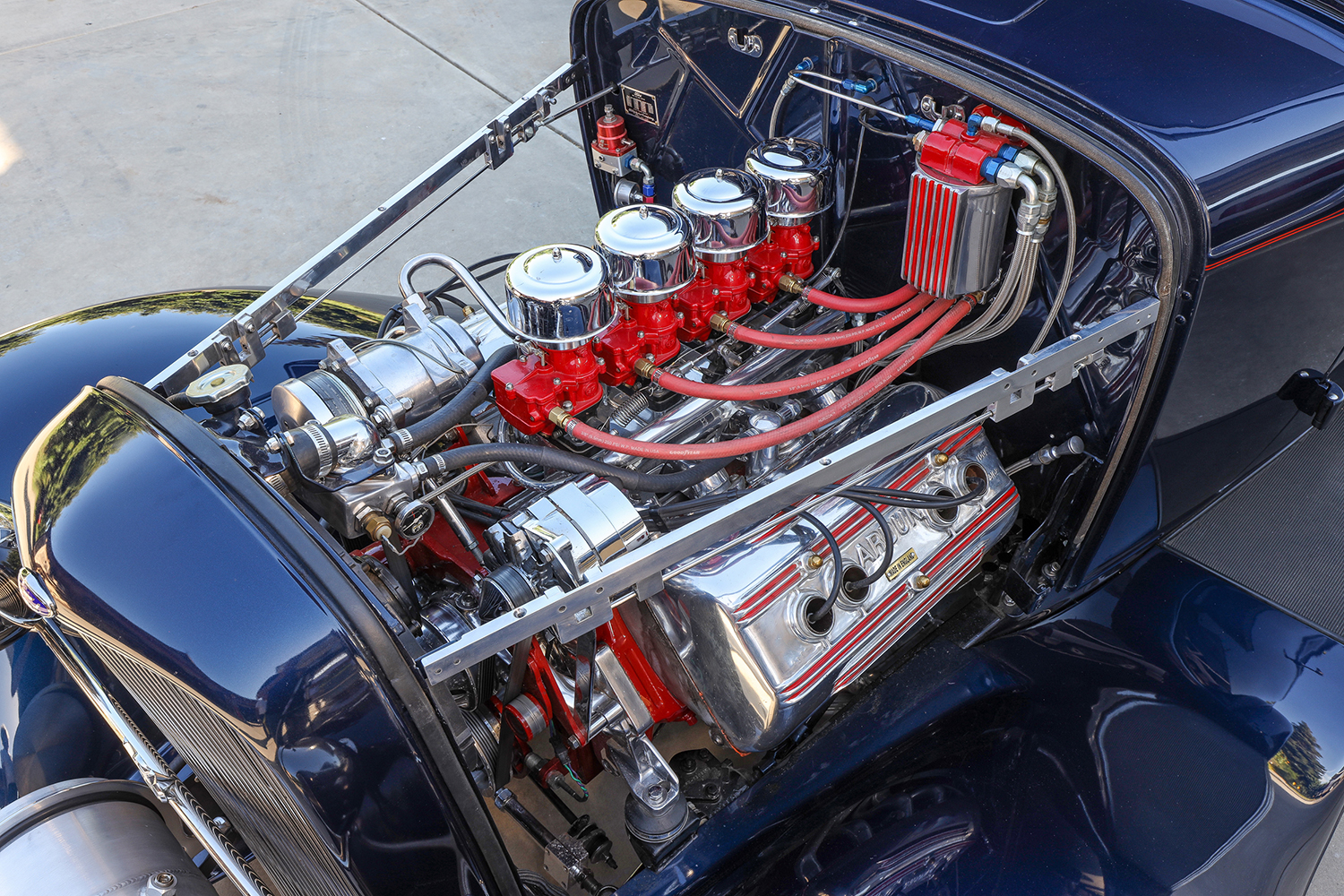

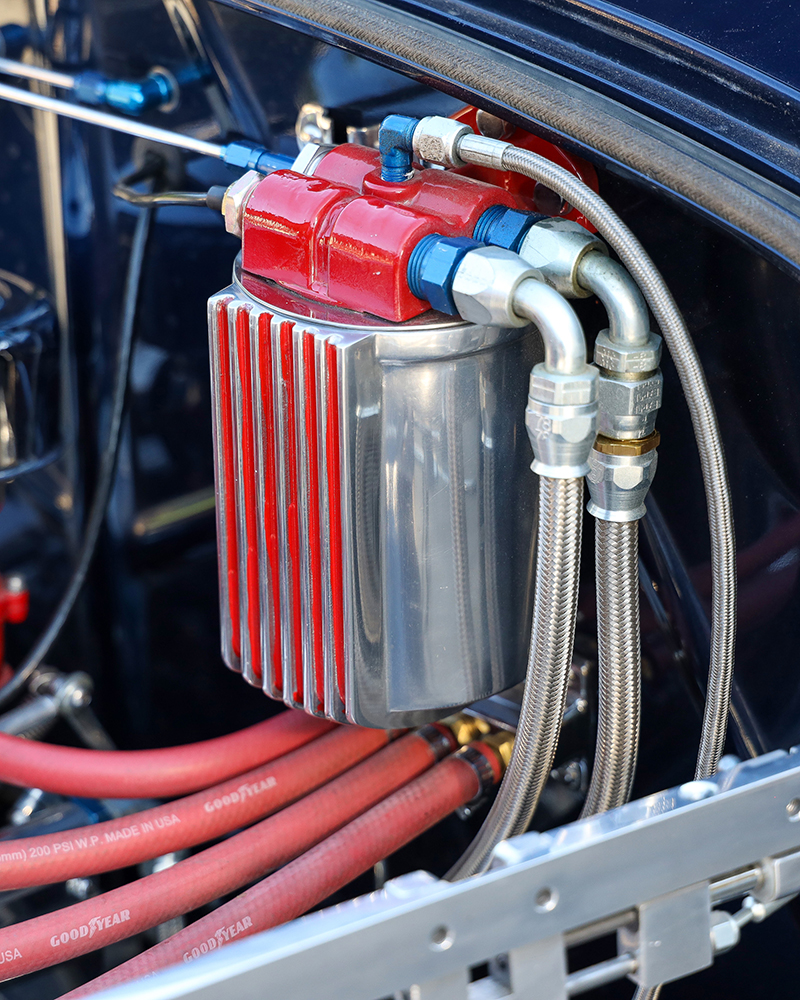

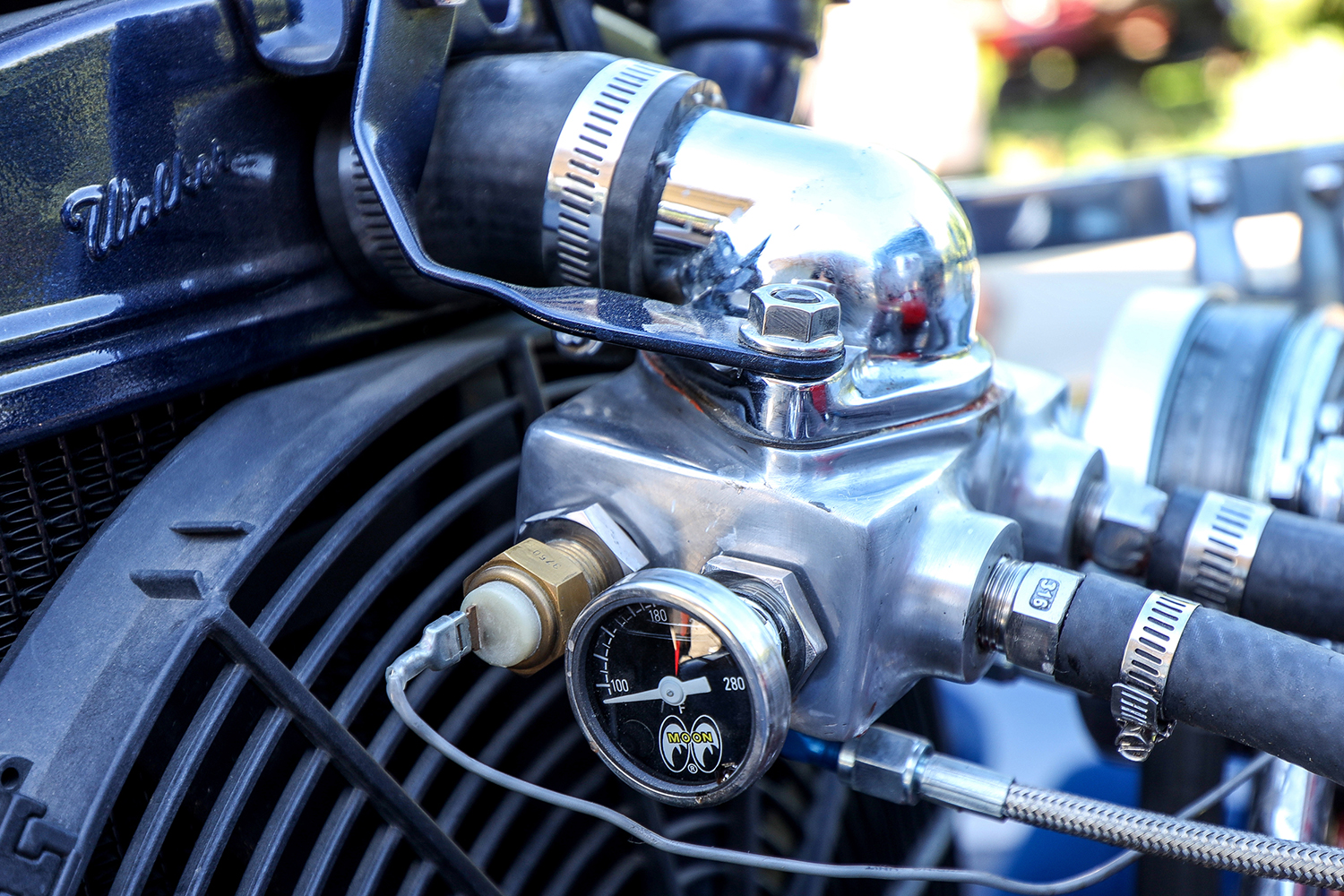

The centerpiece of this hot rod is the ARDUN-equipped cylinder head outfitted Flathead. Based on a 239-inch iron block from 1949, it has been bored and stroked to 275 ci. Additional block modifications include ARP hardware, filled exhaust ports, and improved oil flow. From here, Ross 9.5:1 pistons were dropped into place while the assembly was balanced at B&R Automotive. The name in hot-rodding history and a guru of the Flathead power club is Cotton Werksman, who designed the cam grind, and then Howard Cams cut the profile. The intake is an Austin 4×2 manifold modified to accept a FAST EFI system based on a FAST Sportsman ECU. Sour S&H air cleaners are used, and a Walbro fuel pump supplies the gas. The ignition is based on a 1949 Merc with an MSD crank trigger, 6A box, Blaster coil, and plug wires found on a Chrysler Hemi. The exhaust system was fabricated by Danny Frietas from a 1-1/2-inch header tub, dumping it into a 2-1/4-inch exhaust tubing inline with Borla stainless steel mufflers and tips made in Mike’s garage. Other engine accessories include a reverse flow water pump, a SPAL electric fan, a GM alternator, a Powermaster starter, and a pair of Optima 6V batteries. Linked to the V-8 is an S-10 T5 five-speed that utilizes a Weber aluminum flywheel.

Mike explains, “As I take it out for a drive, the engine purring beneath the hood, I feel the character of every part—the frame, the interior, the paint—come alive like a symphony of steel and artistry. I can almost hear echoes of that sweet rock and roll from my teenage years, resonating through the chassis of what I built, a dream sculpted into reality.” He also takes the time to acknowledge his machinist, the late Bob Skibo, without whom this project couldn’t have happened.

Check out this story in our digital edition here.