By Jeff Smith – Images by the Author

There are a tremendous number of variables to consider when it comes to choosing a camshaft. This makes a story like this difficult to assemble because we just don’t have the space to take all the details into account. A 160-page book might do the job, but we will nevertheless take our best shot.

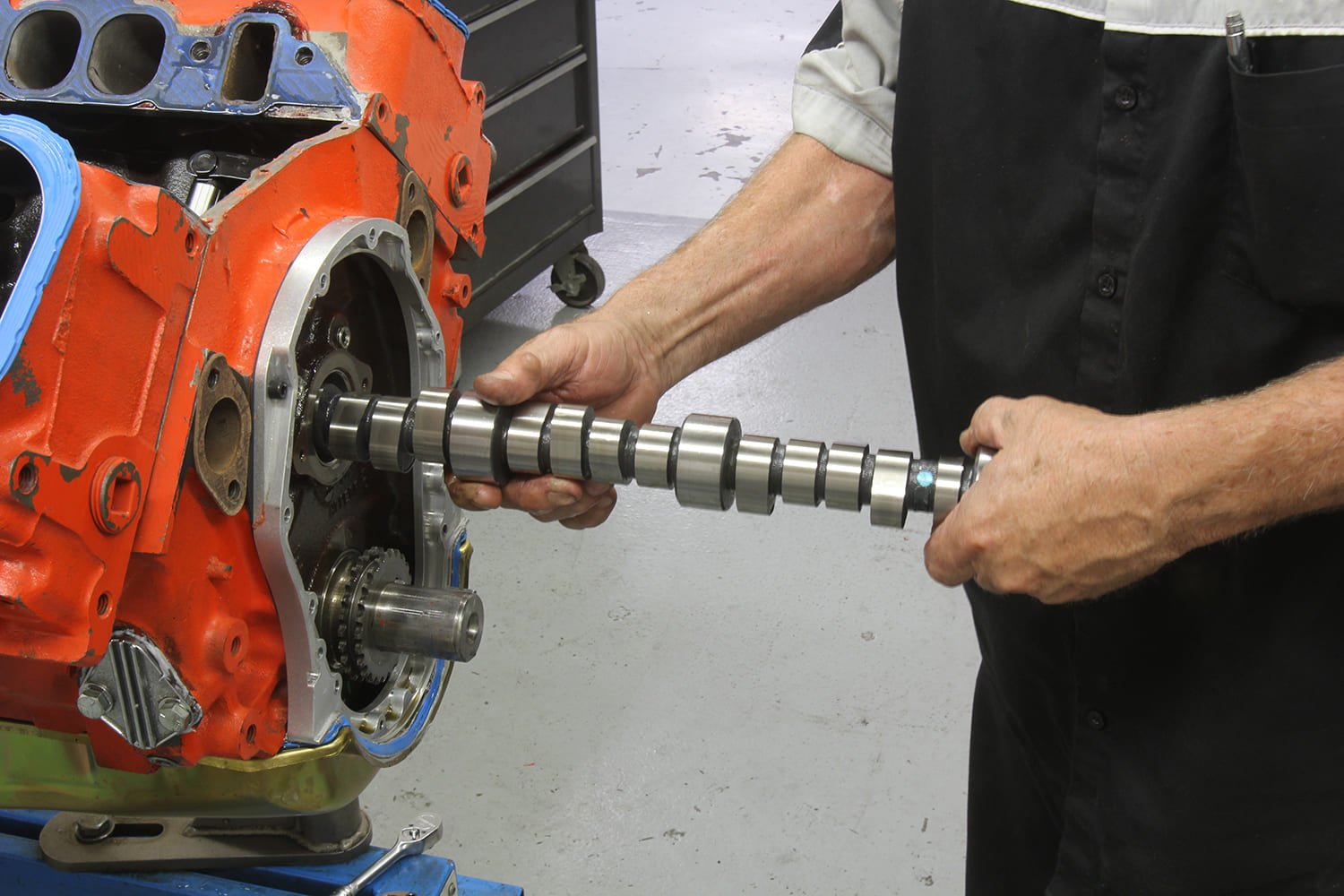

For the sake of brevity, this story will address choosing a streetable, flat-tappet hydraulic camshaft for the classic small-block Chevy. Many of the variables for this selection will carry over to other Chevy engines like the inline-six, big-block, and even LS engine but we’ll focus just on the small-block for this story. Plus, if you choose to go the hydraulic roller cam route, the same cam timing variables also apply. In order to whittle away at the complexities, we’ve created a simple chart that lists the most important items in order of importance. We’ve placed usage at the top of the list since that is the fundamental application that will direct the rest of the decisions. So, let’s dig in.

Frankly, enthusiasts often base their cam choice on how they want the engine to sound at idle. That gnarly, tunnel-rammed, Pro Stock sound is very popular. We get it—there’s a certain allure to how those engines sound. But frankly, Pro Stock engines are 17:1 compression ratio monsters with long duration cams sporting tons of overlap intended to make power between 8,500 and 10,500 rpm. Simply put, these are not street engine parameters.

If something close to that sound is what you want, then low-speed throttle response and driveability is something you must be willing to give up. Engines with big lumpy cams demand richer idle mixtures, offer very low manifold idle vacuum so power brakes will not function, part-throttle carburetor tuning becomes problematic, and generally the engine will run like a pig below 3,500 rpm.

If you are one of those bottom-of-the-page camshaft selection guys, have at it. This story will focus on the rest of the world that just wants a nice-running small-block they can drive on the street and enjoy the feeling of strong overall power.

So, for the remainder of this story, we will focus on street-driven engines that will be used in a 3,300-pound or heavier car with an automatic with a mild converter and sporting roughly 3.55:1 with 26-inch-tall tires. All of this falls under the usage category since this is a relatively typical application for street-driven Chevrolets.

The next position on our variables chart is displacement. This is important because of the difference in stroke. When choosing a camshaft, a 283 is a decidedly different animal compared to a 383- or 400ci small-block. While the bore sizes are different, the real key is stroke. A longer stroke tends to add inertia to an engine at idle so that the same camshaft will run much differently at low engine speeds when used in a 3.00-inch stroke 283 compared to a 3.75-inch stroke 383.

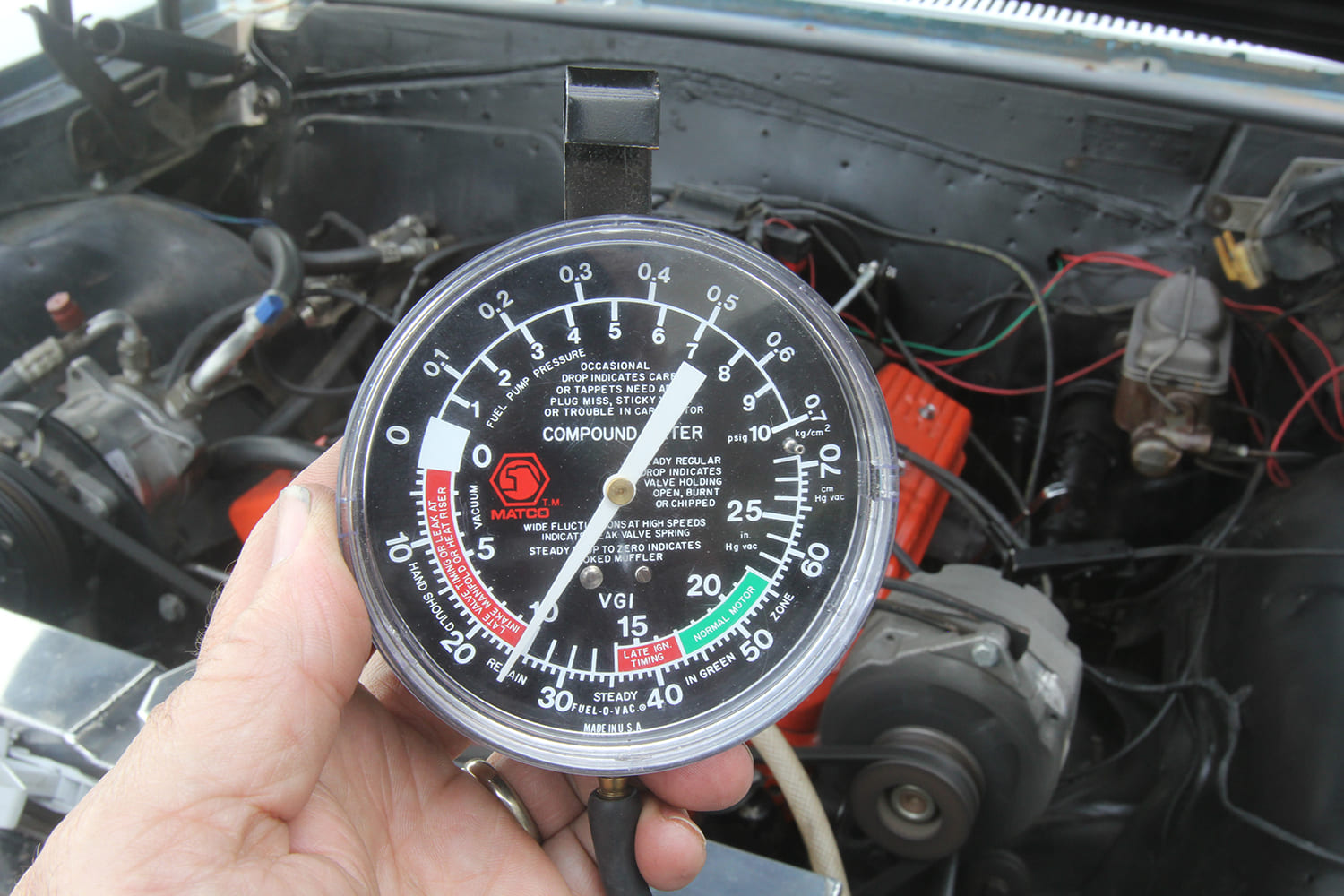

A common description for this situation is that a given cam will be “bigger” in a small displacement engine like a 283 or 302 compared to a 400ci engine. The most significant difference will be in idle quality. Stock engines tend to idle around 17 to 18 inches of manifold vacuum. Adding camshaft duration generally decreases idle vacuum mainly because of the increase in valve overlap. This is defined as the amount of time, measured in crankshaft rotation degrees, when both the exhaust valve and the intake valve are open at the same time.

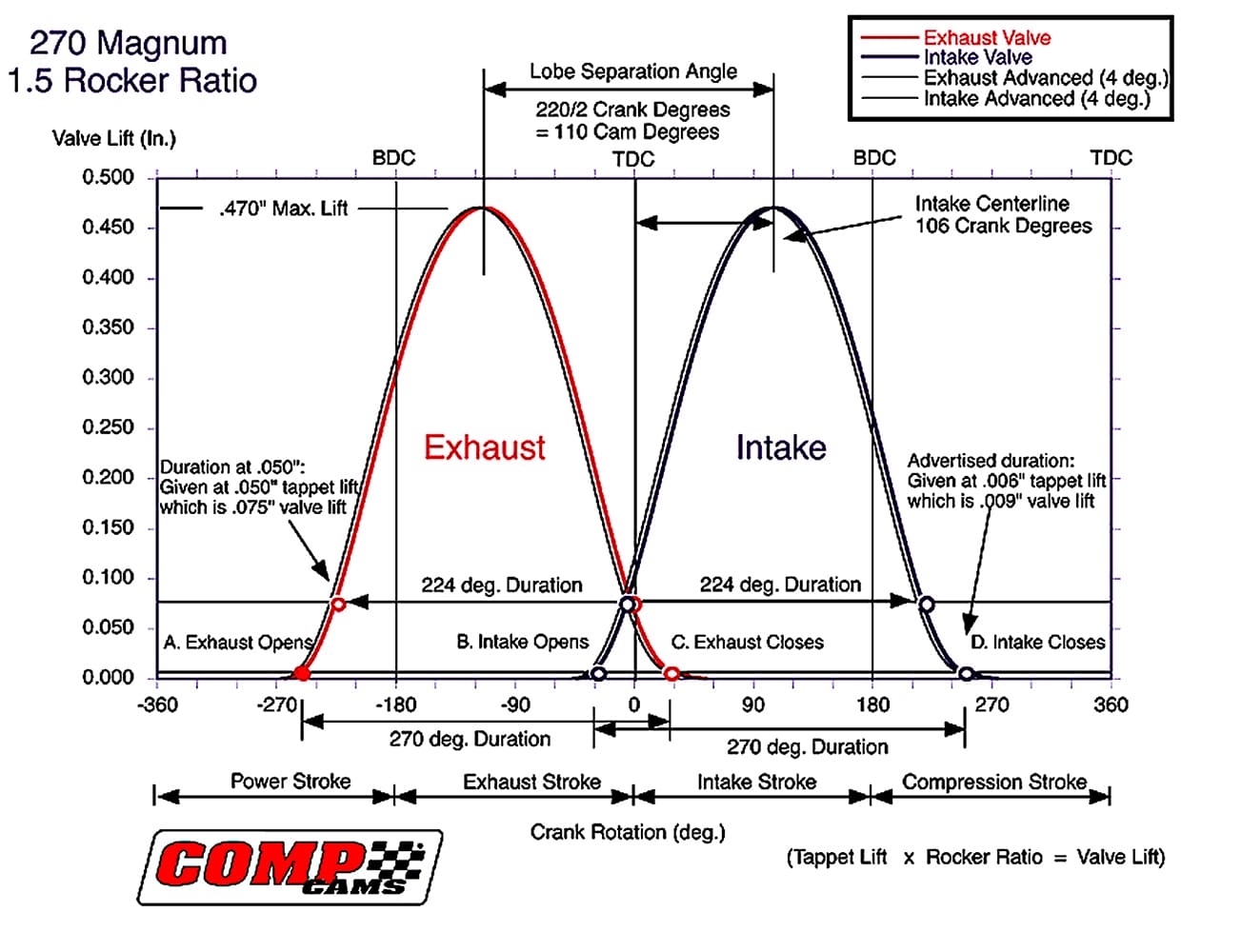

Here is where we begin to discuss how a camshaft operates. A certain amount of valve overlap is essential to making additional power. The “Camfather” Ed Iskenderian called this the Fifth Cycle of engine operation. Assuming all other cam specs remain the same, adding duration to either the intake or exhaust lobe (or both) will automatically increase overlap.

Overlap is usually defined on a cam card as something called lobe separation angle or LSA. This spec is in cam degrees rather than crankshaft degrees but is an indication of the size of the overlap area. This overlap is defined as the number of degrees separating intake opening (IO) from exhaust closing (EC). You can see this amount of overlap when looking at the Comp illustration that shows both the exhaust and intake lobe shapes. The overlap is the small triangle area formed by the exhaust closing point and the intake opening.

A performance camshaft with added duration will tend to bring both the intake and exhaust lobes closer together. This is defined by the LSA. As an example, a stock camshaft may offer an LSA of 114 to 116 degrees while a performance camshaft will bring the lobes closer together with an LSA of 110 degrees. By tightening the LSA, this increases the area of the little triangle of valve overlap, which will decrease idle vacuum. The advantage to increasing overlap is the engine will generally make more midrange and top-end horsepower.

Increased duration generally pushes the power curve upward in the engine rpm operating range. So, a longer duration camshaft like 236 degrees of duration (at 0.050-inch tappet lift) will push the peak horsepower point upward from a smaller cam’s peak of perhaps 5,800 rpm to closer to 6,300 to 6,500 rpm. This higher peak horsepower point also comes with the sacrifice of lower rpm torque.

You can think of the effect of a longer duration camshaft as functioning much like a teeter-totter. We will use the engine’s peak torque as the pivot point for the teeter-totter. A shorter duration cam will make more power on the lower rpm side of the pivot point. If all we do is add a longer duration camshaft, this will slightly move the peak toque point upward in the engine’s operating curve and also tilt the curve to improve power above peak torque while lowering torque below the pivot point.

We will also quickly touch on intake closing point as another important cam position. Intake closing is generally considered the most important of the four main valve events. The later the intake closing point, the more time (in degrees of crankshaft rotation) at higher engine speeds the cylinder has to fill the cylinder. This improves power at higher engine speeds but also contributes to loss of power below peak torque. This can easily be seen in the comparison of the torque curves of the three camshafts.

Based on these factors, the key is to choose a camshaft with more duration than a stock cam but also one that won’t sacrifice power in the operating range where the engine spends most of its time. Here’s an interesting little test. We used a dragstrip simulation program called Quarter Mile Pro that we loaded with a 450hp small-block in a 3,600-pound Chevelle with a TH350 trans and a 3.55:1 rear gear to estimate a quarter-mile time at 12.29 at 112 mph. The program also revealed that the engine spent 90 percent of that 12.29-second elapsed time operating below 5,000 rpm!

There are plenty of enthusiasts who will argue this next point. But the reality is that reducing power below 4,000 rpm with a longer duration camshaft (while slightly improving power above 5,000) will likely slow the car on the dragstrip. The reality is that the bigger camshaft will not help this particular car to run quicker. While the peak horsepower has improved, the simulation reveals that the engine spends less than 10 percent of its time at those higher engine speeds. This means that the limited time at high rpm with improved power offers a very limited opportunity to help accelerate the car.

Torque is a key factor in acceleration. So, if you are looking for a camshaft that will make good power in the midrange where most street engines live both on the street and on the dragstrip, then a cam with a little less duration than a bottom-of-the-page cam is the better choice.

Now that we’ve established some theory to support our cam selection, let’s dive into the cam timing details. Again, we will focus on a typical, mild 355ci small-block with 10:1 compression or less, decent heads, with headers and a non-restrictive exhaust system in a street car with an automatic and a mild converter. Since we want to also have decent idle vacuum of at least 13 inches of mercury (Hg), we will want to keep the duration conservative.

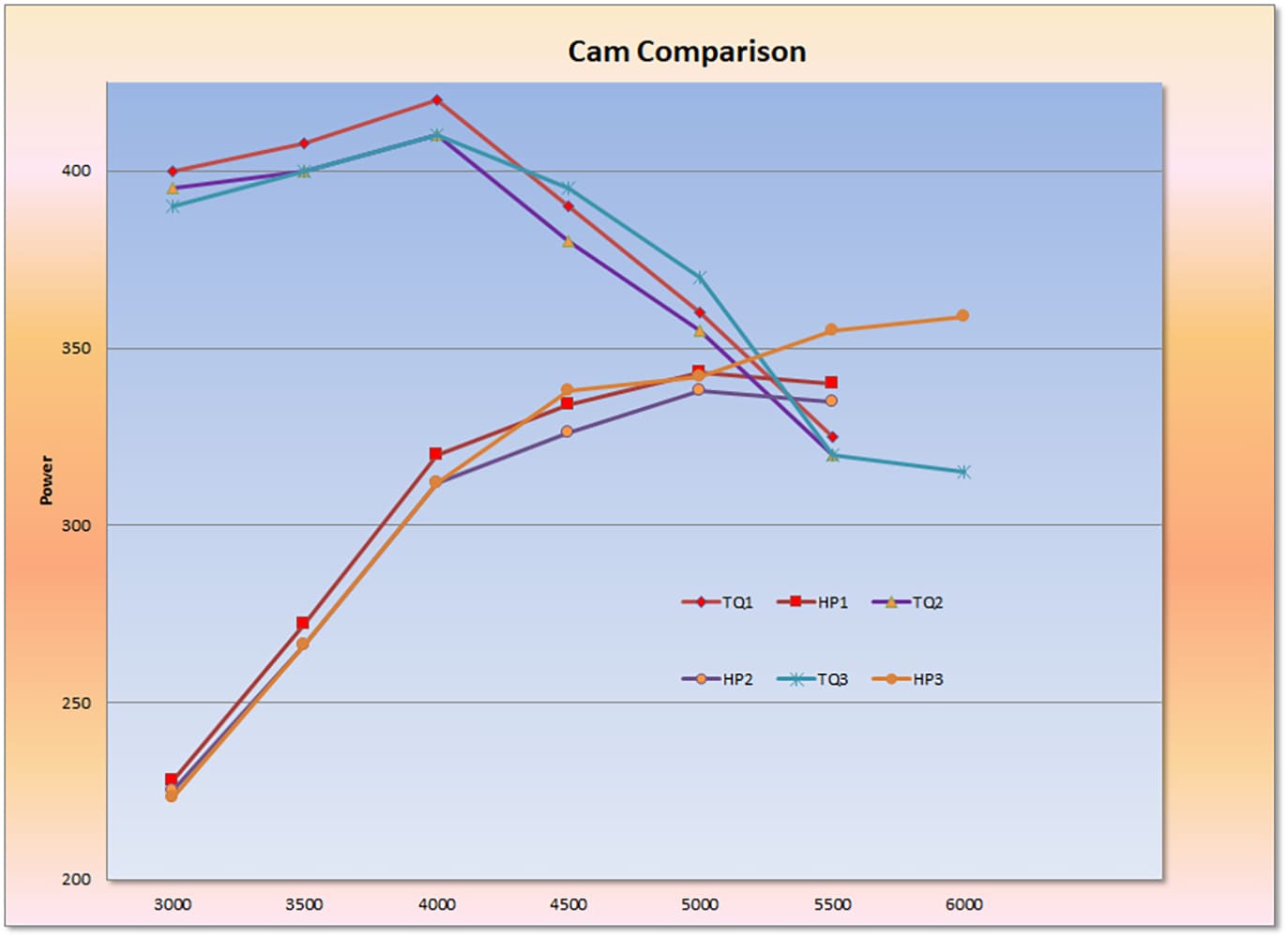

In the accompanying chart, we’ve listed three cams. We used Comp Xtreme Energy flat-tappet hydraulic cams to make the comparisons. Plus, Comp actually performed dyno tests comparing these three cams. If you’ve already skipped ahead then you know, ironically, that the smallest 262 cam outperformed the middle 268 cam and also made the most torque.

As we would expect, the cam with the longest duration made the most peak horsepower but also lost a small amount of torque between 3,000 and 4,000, compared to the small cam. The biggest cam was also better than the midsized cam above 4,000 rpm. It’s worth noting that if the test engine had been equipped with a taller dual plane intake manifold, like a Performer RPM instead of the Performer, and/or if the engine had benefited from better cylinder heads, both the middle 268 and the larger 272 cams would have greatly outperformed the smaller cam.

This brings up an important point. Engine performance is the summation of all the engine’s components. Choosing a big cam won’t necessarily make more power if the other components like compression, cylinder head flow, exhaust, and intake systems are not properly paired to perform in harmony with the cam timing. In other words, stuffing a big cam into a near-stock small-block will likely perform very badly throughout the entire rpm band.

Comp’s dyno testing revealed that the smallest cam made more torque and horsepower than the middle cam, despite the fact that common sense would dictate that the 268 cam should have made more power. That’s why matching all the components is an important part of building a performance engine. This test reinforces that point; even if the differences are small, they are certainly valid.

We’ve covered a tremendous amount of material here in this short discourse. There’s much more to this story than we can cover here but this should offer some insight into choosing the right camshaft for any street-driven small-block. ACP

Check out this story in our digital edition here.

Variables involved with choosing a cam: usage, displacement, manifold vacuum, intake closing point

Camshaft Terms

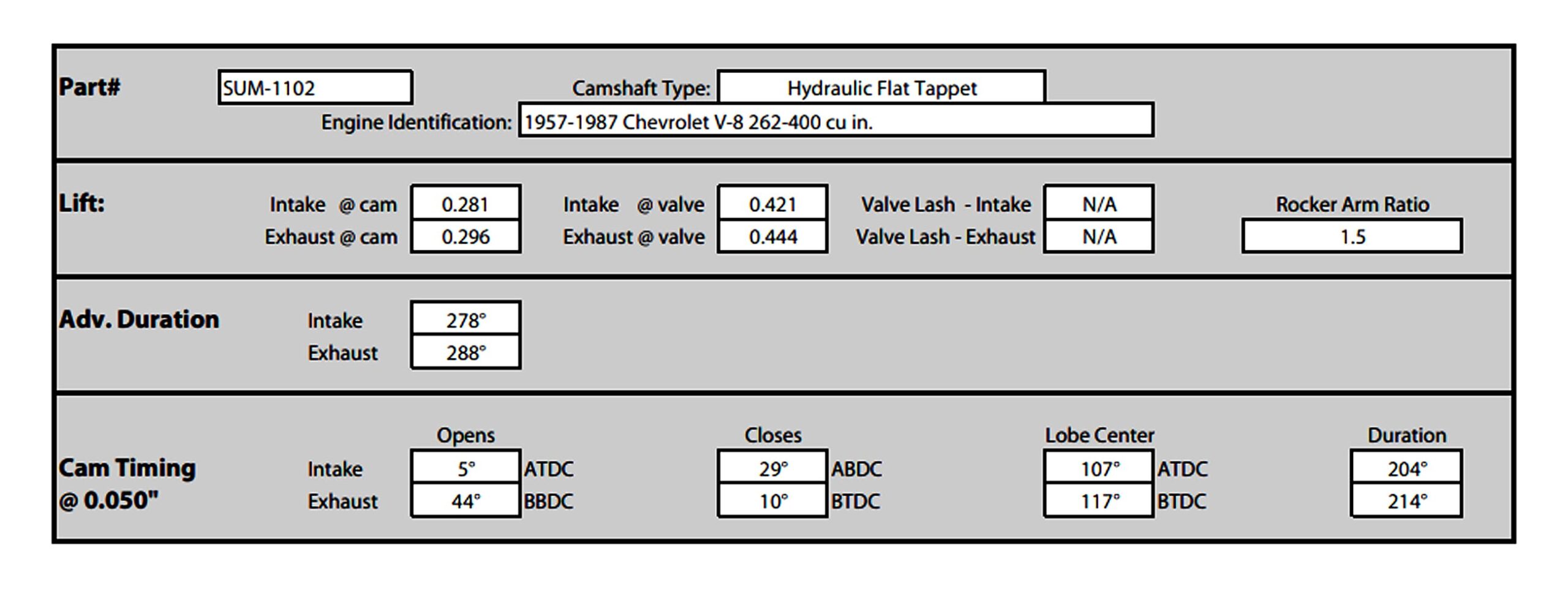

If you are not familiar with the camshaft terms used in this story, these definitions should help you interpret the numbers printed on a cam card:

Lift: This is the amount of valve lift generated by the combination of the lobe lift multiplied by the rocker arm ration. As an example, a lobe lift of 0.330 inch multiplied by a small-block 1.5:1 rocker ration will generate 0.495-inch valve lift.

Duration: This is defined as the amount of time each valve is off its seat and measured in crankshaft degrees. There are two specs. The first is advertised duration usually spec’d with 0.004 to perhaps 0.006 inch of lobe lift. This number will always be greater than the 0.050-inch lift spec. As an example, a cam with advertised duration of 268 degrees will measure duration at 0.050-inch tappet lift of 218 degrees. Because different cam companies use different advertised duration numbers, duration at 0.050 inch is generally used to compare cams from different companies.

Intake Centerline: This is the position of the centerline of the intake lobe for Number One cylinder as defined in crankshaft degrees after top dead center (ATDC).

Lobe Separation Angle (LSA): This is the distance in cam degrees between the intake lobe and exhaust lobe centerlines. As an example, if the intake centerline is 109 degrees and the exhaust centerline is 117 degrees, adding them together and dividing by 2 will create an LSA of 113 degrees. If the LSA and intake centerline are the same number, the cam is ground “straight up” or without advance. But in the above case, the intake centerline is 109 but the LSA is 113 degrees, which means the cam was ground with the intake lobes advanced 4 degrees.

Valve Adjustment: If the numbers on your cam card are listed as 0.000 inch for intake and exhaust this means the camshaft is to be used with hydraulic lifters. If the numbers are 0.020 inch for example, then the cam is ground to be used with mechanical lifters that require the stated amount of clearance between the rocker arm and valve tip with the lobe on its base circle.

Three Cam Cards

All opening and closing points listed below are at advertised duration—0.006-inch tappet lift.

IO = Intake Opening EO = Exhaust Opening

IC = Intake Closing EC = Exhaust Closing

| XE 262 | |||||

| Cam | Adv. Lobe Sep. | Dur. Intake 0.050 | Valve Lift | Angle | Dur. Centerline |

| Comp Xtreme PN 12-238-2 | |||||

| Intake | 262 | 218 | 0.462 | 110 | 106 |

| Exhaust | 270 | 224 | 0.469 | ||

| IO | 25 BTDC | IC | 57 ABDC | Intake ground | 4 degrees advanced |

| EO | 69 BBDC | EC | 21 ATDC | 46 degrees of overlap | |

| (25 IO + 21 EC = 46 degrees) |

| XE268 | |||||

| Cam | Adv. Lope Sep. | Dur. Intake 0.050 | Valve Lift | Angle | Dur. Centerline |

| Comp Xtreme PN 12-242-2 | |||||

| Intake | 268 | 224 | 0.477 | 110 | 106 |

| Exhaust | 280 | 230 | 0.480 | ||

| IO | 26 BTDC | IC | 61 ABDC | Intake ground | 4 degrees advanced |

| EO | 72 BBDC | EC | 27 ATDC | 53 degrees overlap |

| XE274 | |||||

| Cam | Adv. Lobe Sep. | Dur. Intake 0.050 | Valve Lift | Angle | Dur. Centerline |

| Comp Xtreme PN 12-246-3 | |||||

| Intake | 274 | 230 | 0.487 | 110 | 106 |

| Exhaust | 286 | 236 | 0.490 | ||

| IO | 30 BTDC | IC | 64 ABDC | Intake ground | 4 degrees advance |

| EO | 76 BBDC | EC | 30 ATDC | 60 degrees of overlap |

| Intake Closing (IC) Point | |

| Cam | Degrees ABDC (After Bottom Dead Center) |

| XE 262 | 57 |

| XE 268 | 61 |

| XE 274 | 64 |

Power Chart

Comp dyno tested all three of the XE cams on the same 357ci small-block Chevy equipped with Dart S/R heads, Edelbrock Performer dual plane intake, 750-cfm Holley carb, and 1 5/8-inch headers. Note that the smaller XE 262 outperformed the larger XE268 in both torque and horsepower. To be fair, if the engine had been equipped with a Performer RPM intake and/or better heads, the larger XE 268 cam would have made more torque and horsepower than the smaller cam. This emphasizes how engines respond to the entire package and not necessarily to just one component.

| Cam | Torque | HP | Idle Vacuum @ 800 rpm |

| XE 262 | 415 lb-ft @ 3,700 | 348 @ 5,300 | 17.5” Hg |

| XE 268 | 413 lb-ft @ 3,800 | 342 @ 5,000 | 15” Hg |

| XE274 | 410 lb-ft @ 3,900 | 369 @ 5,900 | 11” Hg |