By Brian Brennan – Photography By the Author, Matt Stone & the Ed Iskenderian Collection

Ed “Isky” Iskenderian, who died on February 3, 2026, at the age 104, was a true hot rod pioneer known for speed, craftsmanship, and endless curiosity. Born in 1921, Isky grew up in Southern California during the early, hungry days after the Depression, when ambitious young people repurposed whatever they could to chase the thrill of speed. He once recalled that Model Ts and As—cheap, plentiful, and slow—started as raw material for ambitious kids who wanted more but had little money. “We were kids in the postwar era,” he said, “and we bought used cars for $5 or $10 and tried to figure out how to make them go faster without spending what we didn’t have.”

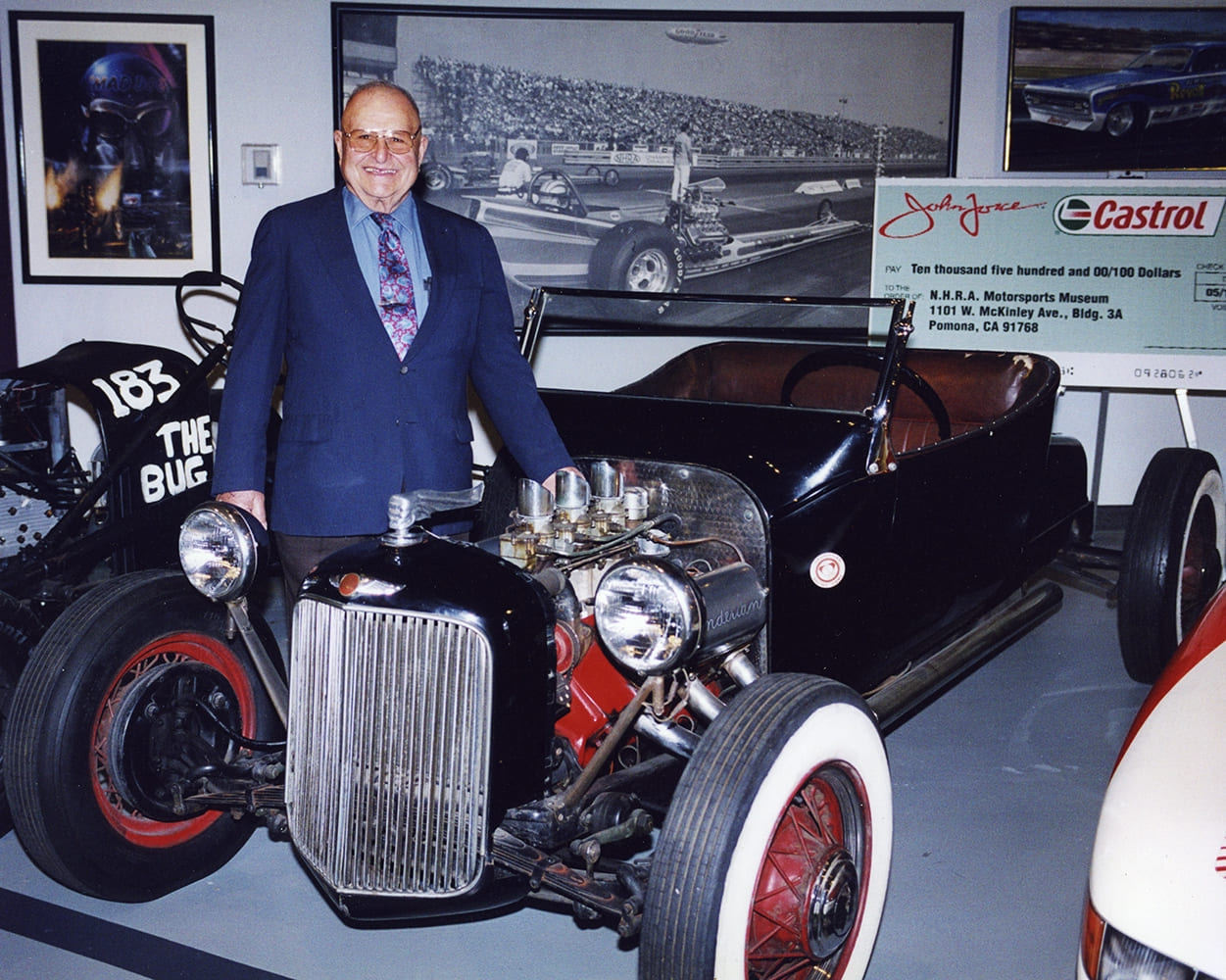

If Isky’s legend is anchored in a single car, it is the roadster that bears his name—the Isky roadster. Its evolution began with a car owned by his lifelong friend John Athan, but the real transformation came from Isky’s hands and mind. Built on late 1920s Essex framerails, the car combined a 1923 Model T body with a Ford B Flathead engine, initially tuned and modified in ways that reflected a teenager’s relentless experimentation. The chassis was upgraded with a 1932 Ford front axle and brakes, and the driving experience was electrified by a then-cutting-edge mix of components from around the automotive world. A distinctive Auburn instrument panel and a two-piece Pontiac grille shell—sourced from junkyards and rebuilt into a unique, aerodynamic front end—gave the car its unmistakable look.

Isky’s early innovations went beyond just the bodywork. He combined a mix of speed parts and homebuilt solutions: a Franklin front axle and air-cooled Franklin steering, a Ruckstell two-speed rearend, and Western Auto Center “air-cooled” tires that were more about brand-name bravado than actual cooling. He experimented with multiple V-8s, ultimately choosing a 1932 Ford Flathead with a three-speed transmission as the core of the roadster’s performance. The engine was a focal point: Isky designed and tested various intake manifolds and carburetor setups, from a homemade four-carburetor intake to later combinations using Navarro and Edelbrock parts. Throughout these trials, his approach mixed practical engineering with a sense of artistry—shown in the hand-fabricated aluminum valve covers bearing his name in a cursive script, crafted with help from his friend Athan.

The roadster’s performance was about more than just speed—it served as a vehicle for learning. Isky’s road trip to Mexico in 1940, before his wartime service, highlighted the car’s durability and the driver’s composure under difficult road conditions. An “eyes wide open” moment during a test run near the Muroc Dry Lakes emphasized the dangers inherent in early hot rodding, but Isky’s calmness under pressure helped him survive and continue improving the machine.

Isky recalls the somewhat tense ride, one that makes you pucker up; he and Athan took it to the Muroc Dry Lakes to test the new engine and some modifications. When installing the 1932 Ford axle and brakes previously, Athan chose to modify the axle and frame to accommodate semi-elliptical springs instead of the stock transverse-leaf setup. Athan created a set of pad-like mounting brackets to adapt these springs to his frame and axle, but they were brazed onto the front of the car rather than welded with more robust steel-to-steel fusing. Before their trip to the dry lakes, Isky noticed that some of the brazing had started to crack, but “hadn’t spread too far.”

However, during a test run on a service road running parallel to the Muroc dry lake speed course, the front axle broke off. Isky was driving the car, wearing a borrowed “helmet” (again remember this was probably a military surplus open-face canvas or leather lid, with no thought of seatbelts, rollbars, fire suit, or other safety gear). Luckily, Isky was able to keep the car under control with minimal damage, and neither of the young occupants was hurt. It could have been Isky’s last ride, a thought Isky dismisses by saying, “Perhaps the man upstairs might have thought he needed a camshaft someday, so I was spared.”

By now, you might be curious about what kind of camshaft this car has used all these years. Interestingly, the story of its camshaft and this car itself helped lead to Isky entering the cam grinding business professionally. For a while, he used a camshaft made by his friend and mentor, the great Ed Winfield, but later switched to one of his earliest Isky Racing Cams designs. And it all worked out, too.

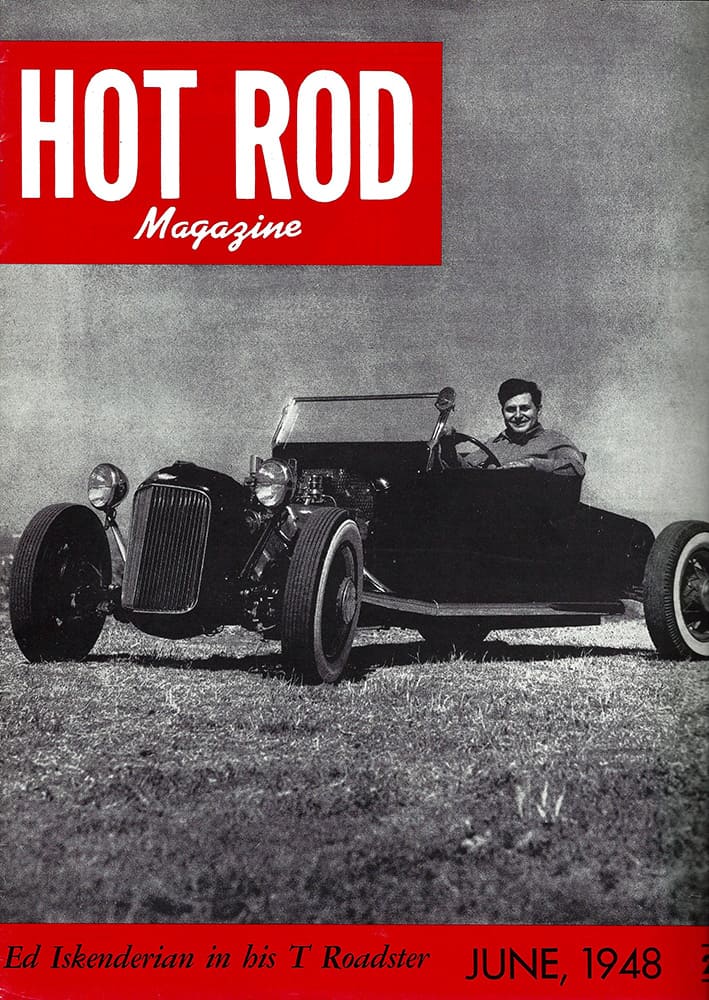

The car eventually reached speeds over 120 mph, as indicated by an engraved timing plate on the dashboard. Its fame grew: Hot Rod magazine named it “Hot Rod of the Month” and featured it on the cover in June 1948, solidifying Isky’s reputation as a notable builder and racer.

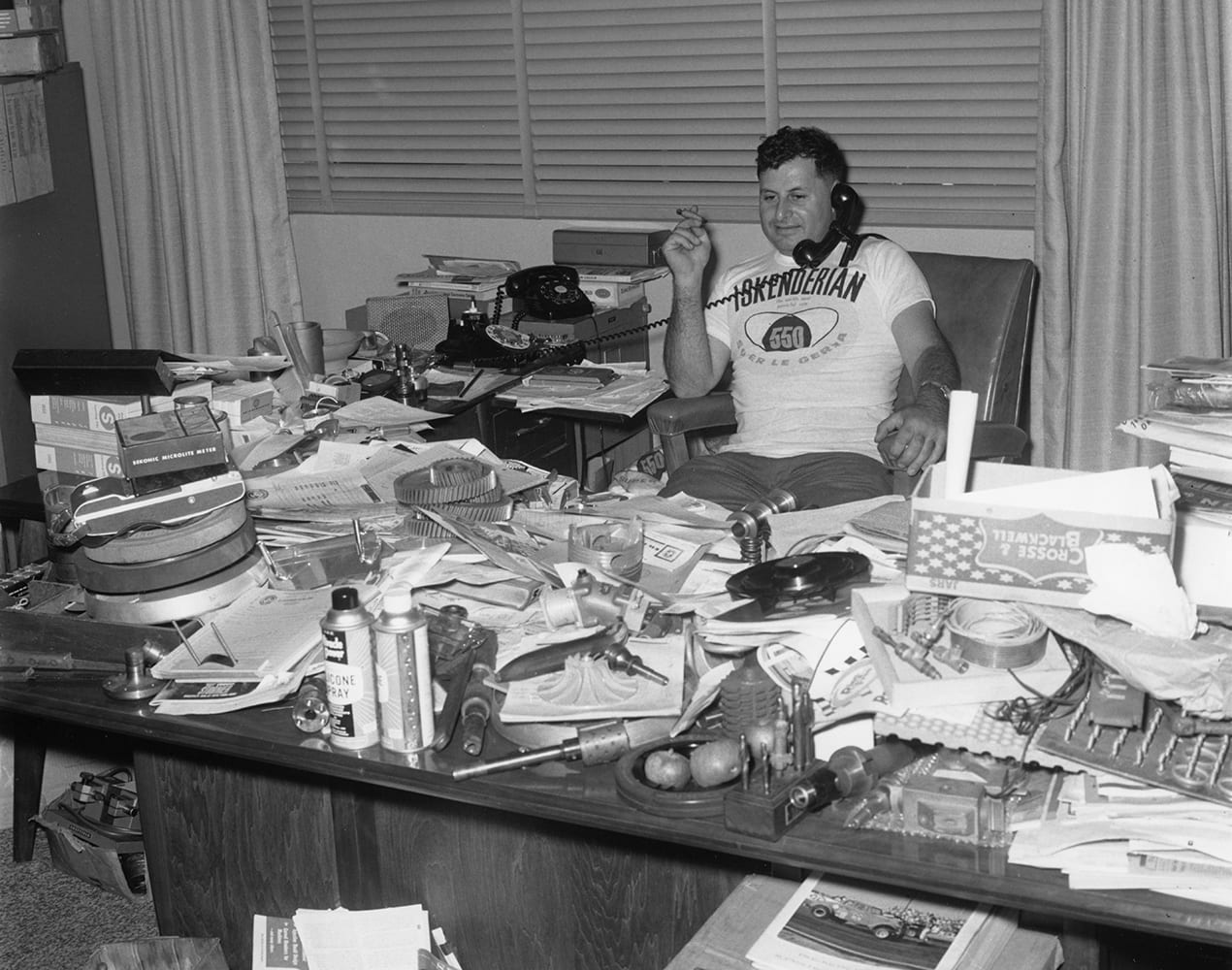

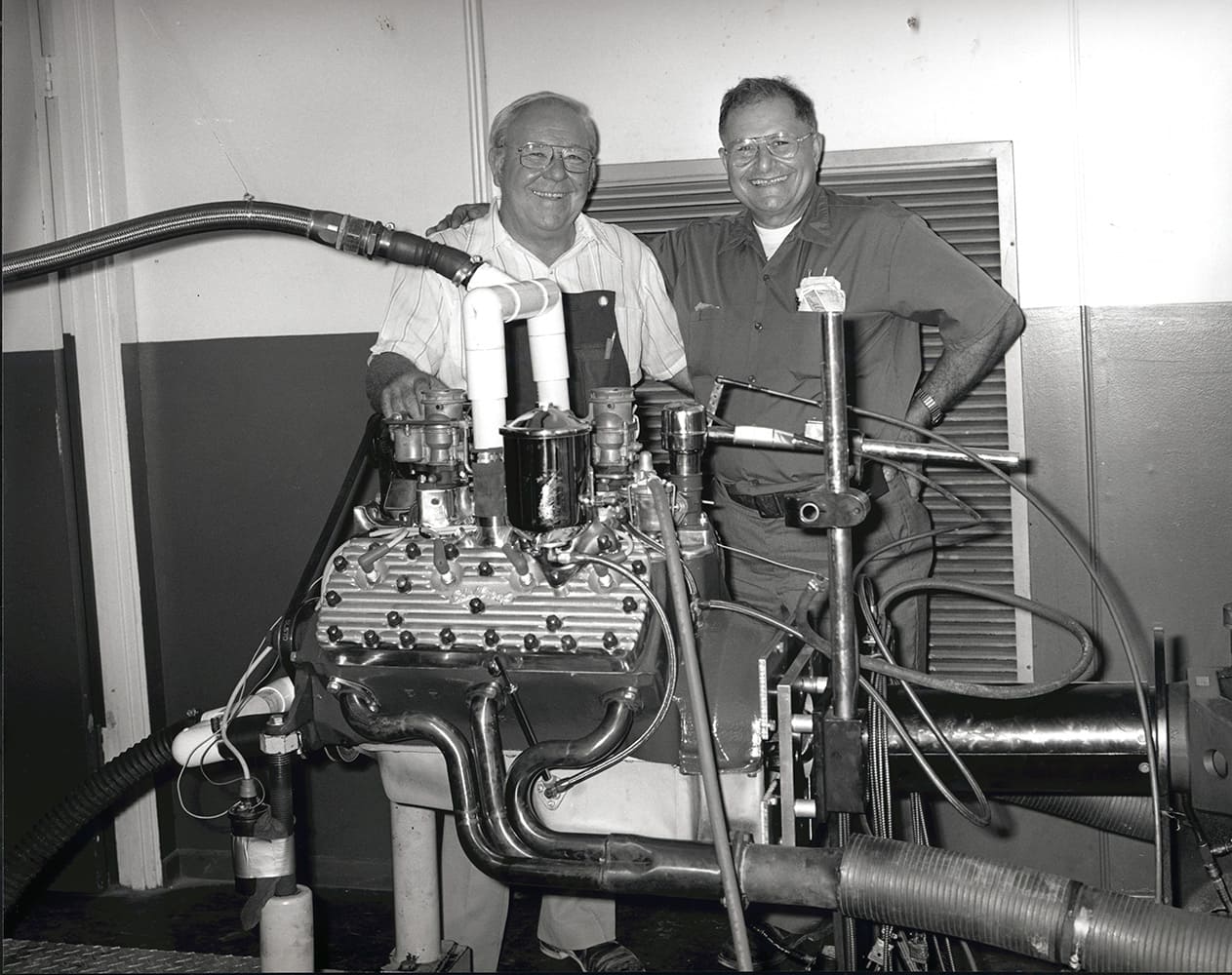

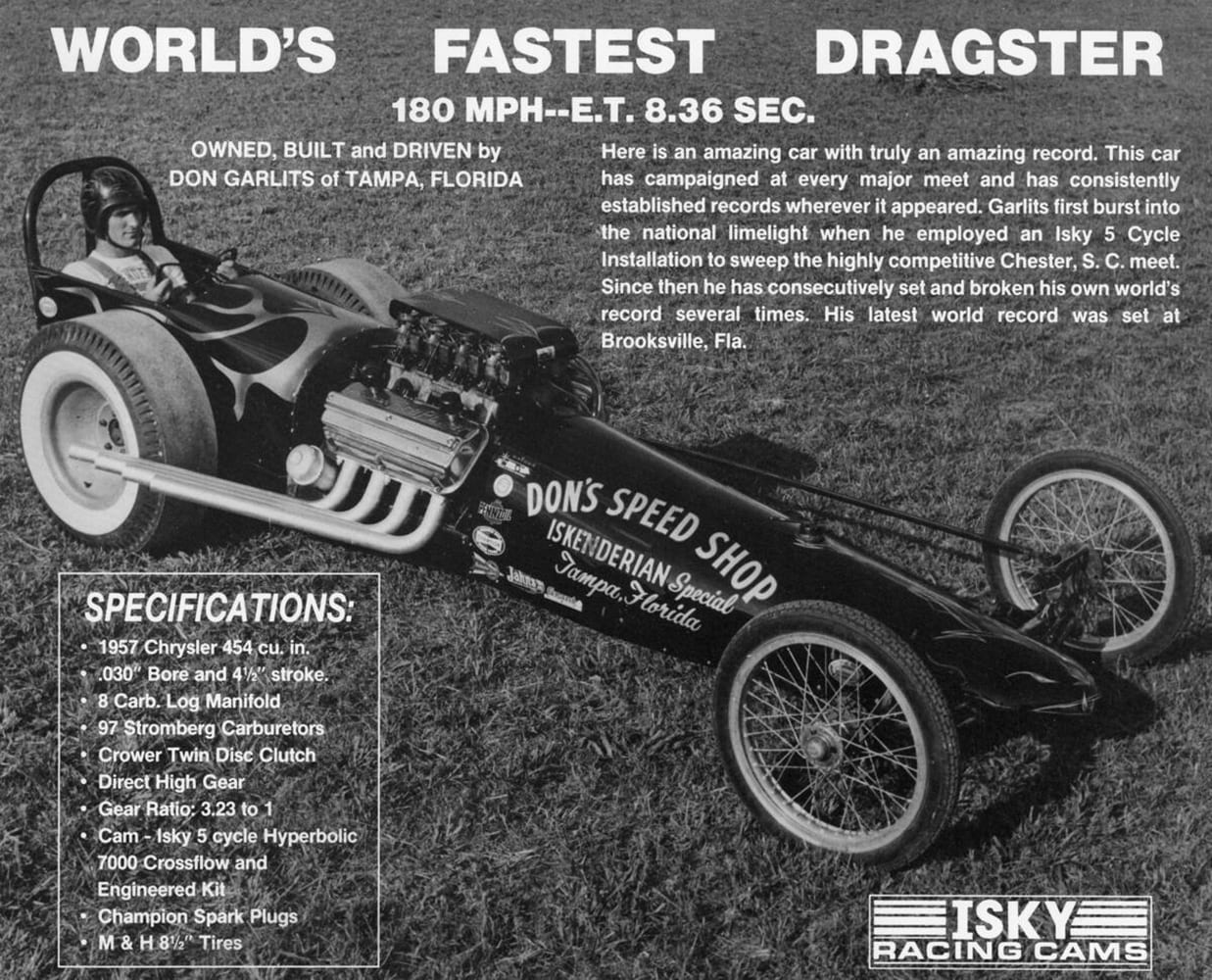

Iskenderian’s life’s work went well beyond his own car. He started Isky Racing Cams, a business built from his curiosity about why engines perform the way they do and how to improve them. Early work with Ed Winfield and his developing cam designs made Isky a key player in the American speed parts scene. His camshaft company became a proving ground, helping many hot rodders and racers push engines to higher rpm and achieve more reliable power. Isky’s entrepreneurial spirit matched his technical talent: by the mid ’50s, he was managing a growing business while raising a family, expanding his influence from backyard tinkering to a respected name in the industry.

There is so much more to say about Isky and his life, but we would need many more pages. You can find a more in-depth look at Isky, his life, his hot rod, and Isky Cams in the two-part series written by Matt Stone for Modern Rodding that appeared in the Feb. and Mar. ’21 issues.