The Early Days of Racing, Speed Shops & the Performance Industry

By Greg Sharp – Photography Courtesy of the Greg Sharp Collection

It would be easy to just list his vast number of accomplishments and still have a plenty long story. But it wouldn’t tell you about the man. By the time you read this, he will have celebrated his 99th birthday. And he’s still vital, charming, witty, kind, and the very definition of a class act as he ever was. He can fit in virtually any situation or crowd. He was on the ground floor of the speed shop business as well as trade shows. He’s been a racer, a retailer, an editor, a promoter, and a filmmaker, and has done it all with style.

If you were fortunate enough to be around Alex Xydias and his close friend of seven decades Wally Parks you would soon see they were two of a kind. Both were real gentlemen who still had no problem busting the chops of the other. “Can we go now or are you going to sign autographs all night?” was one of the more common jabs.

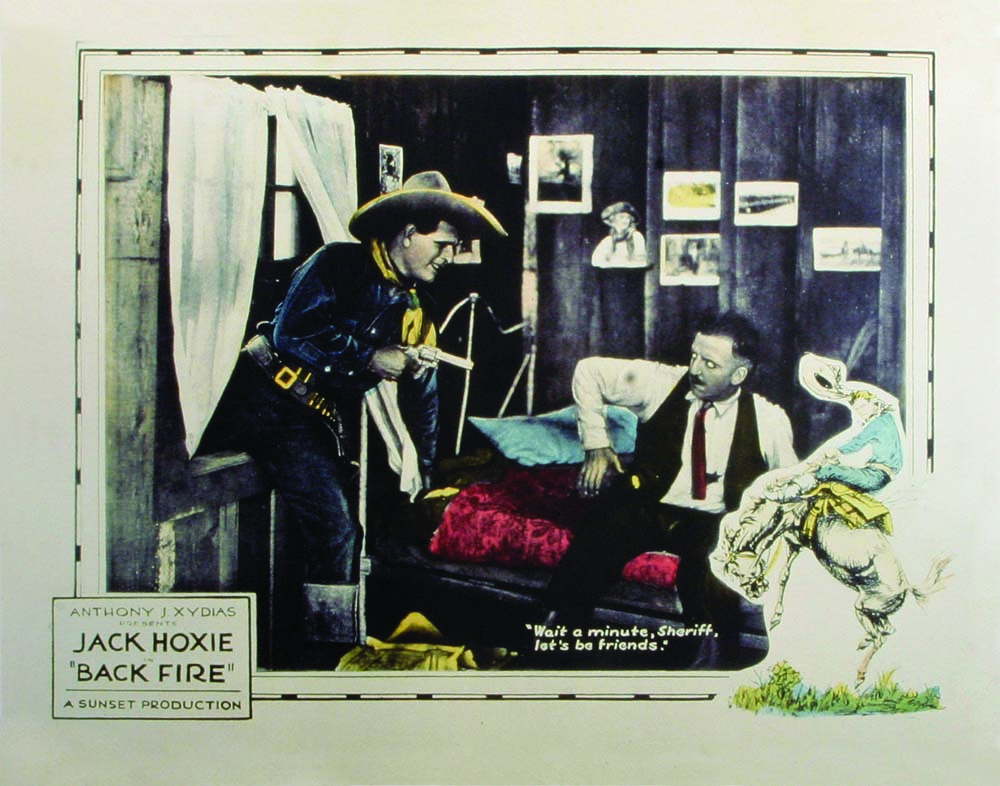

Alexander Basil Xydias literally grew up in Hollywood. His father Anthony was a Greek immigrant who raised himself up from running a small theater in Mississippi that catered to World War I soldiers in nearby Camp Selby but by the early ’20s had moved to Hollywood and became a movie producer under the title Sunset Productions. By 1928, young Alex lived in a big house on Crescent Heights Boulevard complete with a maid and a new Auburn or Cord in the driveway. Sunset Productions made dozens of movies, many of them westerns starring silent film hero Jack Hoxie. Then, a year before the Depression, it all came apart. Anthony developed prostate cancer. He survived, but his recovery took so long that he completely missed the conversion to talking pictures. His business failed and with it his marriage.

It’s tough being a single parent any time, but especially so for a single mother during the Depression. Alex’s mother rented out rooms and became a fortune teller (Madam X). Young Alex went from a life of opulence to peddling magazines and newspapers on the streets of Hollywood. But it wasn’t as disastrous for him as you might think. He was still young and the Depression had affected nearly everyone.

His mother did well enough to send Alex and his sister, Carolyn, by bus or train to stay with her brothers and sisters in Mississippi for the summers. It was a culture shock to be sure but Alex remembers it as some of the greatest times he ever had. He worked with his cousins to make enough money for a cold root beer in the afternoons and even picked cotton for 25 cents per hundred pounds! It was certainly a long way from Crescent Heights Boulevard in Hollywood.

Alex went to Laurel Elementary then graduated from Bancroft Junior High with Judy Garland and Jason Robards. He went to Fairfax High School with Mickey Rooney (who was rarely in class) and Ricardo Montalbán (long before Fantasy Island and “rich Corinthian leather”). The other great thing about Fairfax High was it was kitty-corner from pioneer customizer Jimmy Summers’ shop and just a couple of blocks north of Gilmore Stadium where Midget car racing reigned supreme.

While riding his bicycle around Hollywood running errands for his mom, he was sent to a market on La Brea to buy a sack of potatoes. Coincidentally he happened on a gas station and repair shop at La Brea and Oakwood. They had Midget race cars in the back shop and Alex was fascinated watching the Midget cars being maintained. Years later he would learn that the Brea Wood Garage was operated by Vic Edelbrock. Little could young Alex have imagined how much the Edelbrock name would be involved in his future.

Read More: Ford Never Had This in Mind When Designing the 1971 Ford Ranchero

By the late ’30s Alex had a job working in a gas station and became fascinated with the souped-up cars and hot rod roadsters (they weren’t yet known as hot rods) that came by the station. He got his first car, a blue $65 1929 roadster before he even had a driver’s license. He still remembers his embarrassment when his mother had to drive it home. Once he was licensed, he drove it to Fairfax but had to push-start it every day because he didn’t have the $1.50 for a new battery. He took auto shop at school and tried to learn everything he could to keep his roadster on the road. After graduation, he was making $10 a week at the station. But a job at a defense plant in Vernon working on 105mm artillery pieces paid $23 a week so he stepped up from a 1929 roadster to a black 1934 Ford 3-Window Coupe. With dual pipes and Porter mufflers, he could really make noise going down Yucca Street toward Hollywood Boulevard in low gear.

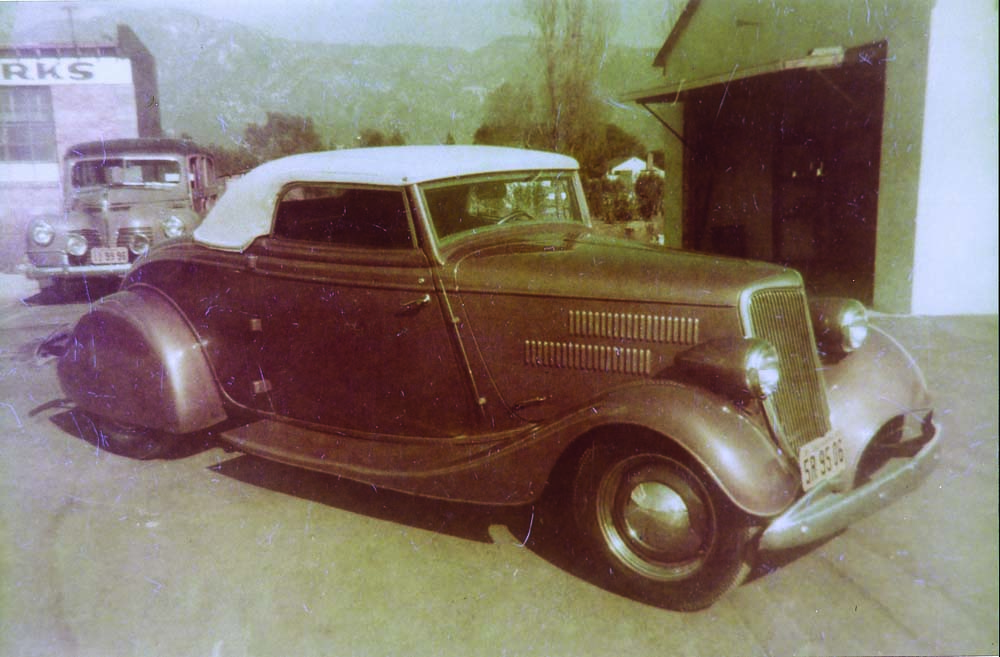

Until he couldn’t. Too many noisy trips down Yucca flattened the crank and loosened the rod bearings. Rather than fix it he got a lead on a customized 1934 Ford Cabriolet in the basement parking lot of the swanky Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard. He bought it from the mother of the owner who was probably in the service. It was unfinished when Alex bought it in 1942, but before long he had it painted metallic blue and drove down to 4910 South Vermont Avenue to have a black Carson Top installed.

Among other things, it had solid hood sides with 40 louvers on each side, chopped windshield, and side windows, and front fenders smoothed and extended down the length of the doors in place of running boards. Later it was painted a rich gold and became known as the “Jewel.” But the real highlight was the rear fenders that were solid and resembled the wheel pants of streamlined airplanes of the ’30s.

Coming full circle to his high school days, the work was done by Jimmy Summers. So how did you change the tires? Wingnuts were installed inside the trunk and Alex had some of the first “puncture-proof” tires and never had a flat. Finishing touches were La Salle headlights, 1939 Ford teardrop taillights, and 1940 Olds bumpers.

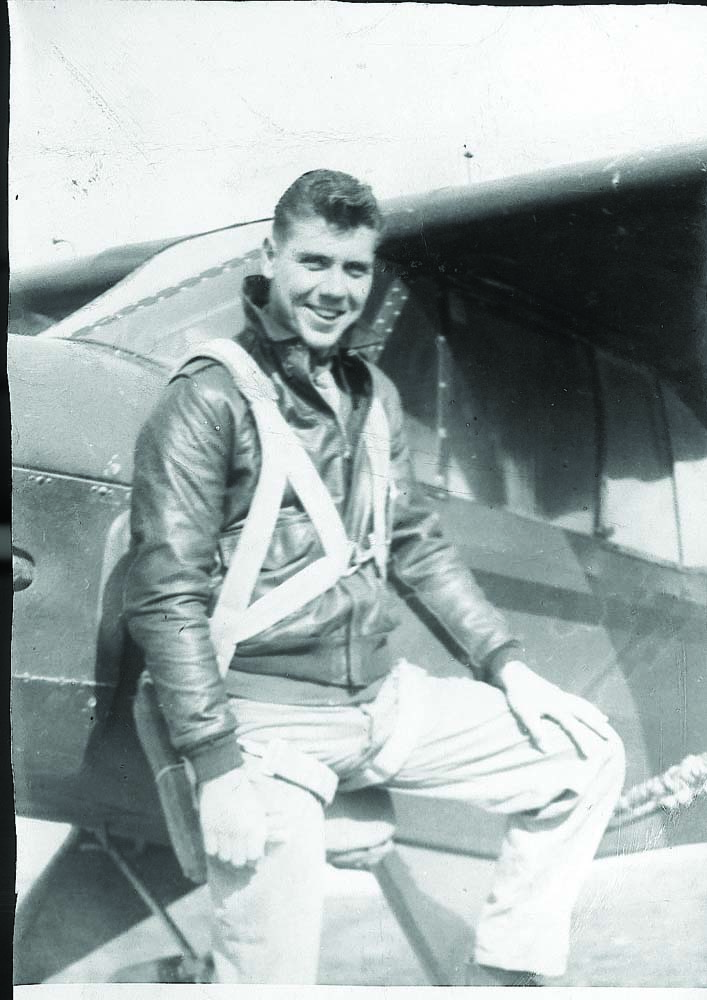

Then World War II reared its very ugly head. Alex wanted to be an airplane mechanic and enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He worked on P-40s and B-25s and spent much of the war as a flight engineer and top turret gunner on B-17s. He never saw combat, but jokingly suggested that he is sure it was because “the Germans heard I was coming and surrendered!”

But why a speed shop? Thinking of what they would do when they got back to civilian life and talking about cars was a major activity of off-duty GIs. Alex, like so many, had learned to use pretty sophisticated tools and equipment. He had briefly experienced the dry lakes racing scene before the war and some street racing when home on leave. He kept up with what the other racers did during the war with Veda Orr’s newsletter.

Veda’s husband, Karl, owned one of the few speed shops around out on Washington Place in Culver City. Alex just liked the sound of the words “speed shop.” Southern California had a magical name even then but was too cumbersome for a title, so he came up with the abbreviated So-Cal.

The day he mustered out of the service on March 3, 1946, using $100 borrowed from his mother, Alex opened So-Cal Speed Shop at 1806 North Olive Avenue in Burbank, California. (Hollywood seemed too sophisticated to Alex for a speed shop but Burbank had aircraft plants and movie studios where young guys home from the war made enough money to spend on their hot rods). He had no idea how it was going to work, but he was willing to take a risk. He couldn’t afford to stock expensive items like heads and manifolds, so he started off with goodies like chrome acorn nuts, carburetor stacks, and Sta-Lube oil.

Some months he barely made $100, but the government offered a supplement for vets who went into business for themselves. Plus, there was the “52-20.” Vets were given $20 a week for a year to help them get re-established. A young ex-sailor named Keith Baldwin cruised by in his 1939 Mercury coupe, saw the “Speed Equipment” sign, and stopped in. Alex gave him a quarter discount on a $1.25 chrome stack and the pair immediately hit it off and became best friends. Alex remembers Baldwin’s intelligence and honesty and said he couldn’t have made it without him.

Sometimes the pair just lifted weights waiting for customers. Early on Alex was in the wheel business. No, not aluminum or mags. Those were still a decade or more away. But guys wanted to run steel wheels instead of the spokes on their hot rods and Alex bought every steelie he could get from Ford dealers and sold them almost as fast as he got them in.

As Alex’s one-year lease was running out, he again took a risk. He bought a pre-fab 20×20-foot garage from Sears and Roebuck. So many returning hot rodders were in the building trades that it was no problem at all getting the garage built on a lot at 1104 South Victory Boulevard. Once more, Alex’s intuition paid off. He reasoned that if he put the garage on the back of the lot, he’d eventually be able to add a showroom and sales counter at the front.

Read More: Firing Up – Drivin’ Tunes

At first, they didn’t even have a bathroom (they used the one in the drive-in restaurant across the street). Once he added the showroom on the front there was a bathroom, but it soon gave way to the Kong Ignition “division” of So-Cal when Alex took over Jackson’s business so Kong could fight in the Korean War.

Alex tried to recruit Baldwin, his first customer, to come work for him, but Baldwin had a good job with Ford. Instead, his first hire was tall, lanky, and opinionated Doane Spencer. It soon became clear that Spencer’s talents as a fabricator were without peers. After all, his Deuce roadster is one of the most iconic hot rods in history. When Alex was finally able to hire Baldwin, he said it changed everything. “We were finally able to build racing engines and become a real speed shop rather than a parts store.”

When Hot Rod magazine began in 1948, Alex being conservative as he was, held off buying an ad for a couple of months. When the ads finally appeared in Hot Rod the shop began to take off. He published a 25 cent catalog with the legend “Only the Best in Speed Equipment” and orders began to roll in. He recalls the fun of taking the mail home and pouring quarters all over his apartment. Another customer, Dick Flint was hired as a one-man shipping department. Flint recalled thinking they had really arrived when they got their own So-Cal–imprinted packing tape. Ironically, two of So-Cal’s earliest employees, Spencer and Flint, built roadsters that, more than five decades later, were featured at the prestigious Pebble Beach Concours d’ Elegance and sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction.

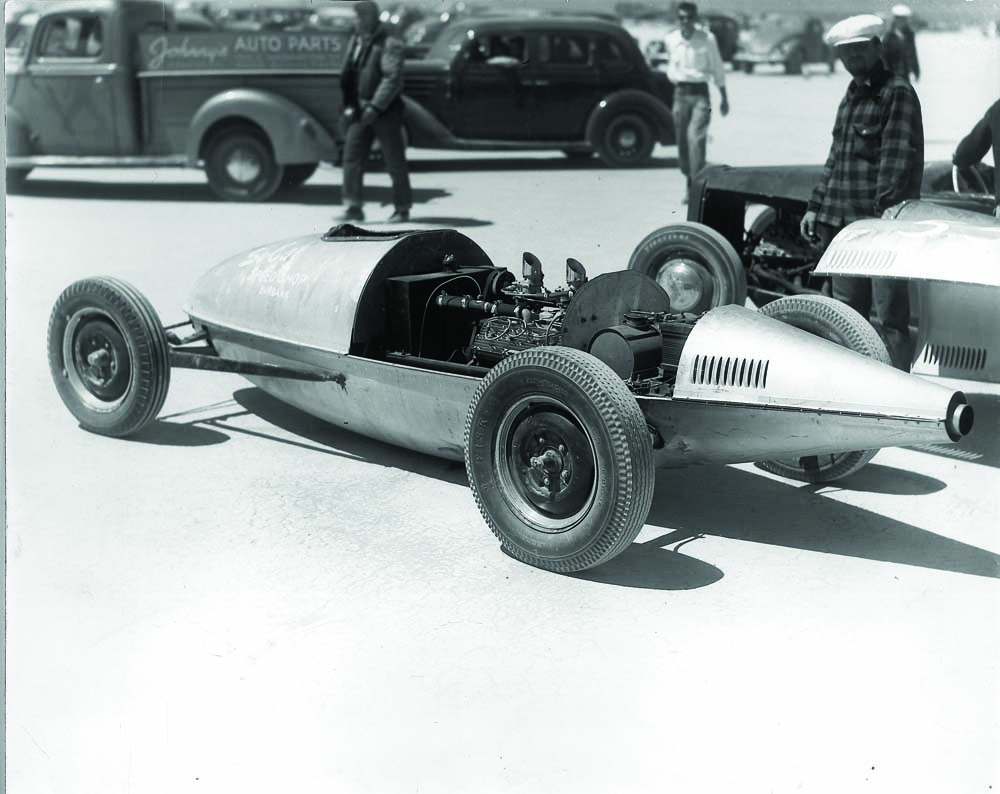

Once more, Alex’s instincts kicked in. He reasoned that if you’re going to have a speed shop you should have a race car to promote it. Alex was an admirer of Bob Rufi since he became the first dry lakes racer to exceed 140 mph in 1940. Rufi’s car was only powered by a little four-cylinder Chevy topped with an Olds four-port head, but the speed came from the streamlining of a tiny teardrop-shaped body. After the war, Bill Burke started building cars from the surplus belly or wing tanks. He was inspired by seeing them unloaded in the South Pacific and a little measuring determined that they were big enough to hold an engine and driver. In all, he built 13 original tanks based on Model T frames. With a war surplus fuel tank for a body, a pretty inexpensive, pretty fast race car could be built.

Back when he first became a fan of Midget racing, Alex had been attracted to the little Ford engines known as the V8-60. And who better to build one than Bobby Meeks the man responsible for the Edelbrock Midgets. The little engine was bored and stroked to 156 ci, placing it right in the middle of SCTA’s Class A. In April 1948, a brand-new untested race car handled by a brand-new untested driver made its way across the barren El Mirage Dry Lakebed. The “break-in” run was a smooth but less-than-impressive 87 mph.

But it was a start, and driver and race car went home in one piece. Before the 1948 season was over, the little V-8 pushed the tank to a best speed of 132.93 mph and raised the A/Streamliner (tanks were not yet known as lakesters) record to 130.155 mph and scored 1,300 points (more than any other member) for Alex’s Glendale Sidewinders club.

Furthering the shop’s image, the car was painted in what was to become the familiar So-Cal scallop in white and Pontiac “Trumpet Gold,” the same as Alex’s “Jewel” customized 1934 Cabriolet. Not just fast but also pretty. Its performance and appearance earned it the cover of the Jan. ’49 issue of Hot Rod magazine as Hot Rod of the Month complete with a Rex Burnett cutaway drawing. After the appearance in Hot Rod, business got even better, with orders coming in from all over the country.

With the lakebed surface often breaking up badly, the racers began to look for other suitable venues. Wally Parks (soon to become Hot Rod editor), Robert E. Petersen (publisher of Hot Rod), and Lee Ryan, a Petersen advisor, traveled to Salt Lake City to ask permission for hot rodders to use the Bonneville Salt Flats. When they got back to SoCal (the area) hot rodders were anxious to run on the flat, nearly endless surface. Alex realized it was something very special as it previously had only been used for land speed record attempts and was to be taken advantage of. Dean Batchelor, a So-Cal customer since the second day of business and the first racer to letter So-Cal Speed Shop on his 1932 roadster, began to have an idea about building a streamliner. It was decided that Batchelor would sell his 1932 roadster to raise some capital and Alex would take the body off the tank.

Batchelor attended Chouinard Art Institute and worked at Lockheed Aircraft in Burbank. Up to this time, land speed record cars (mostly British) were huge and usually powered by multiple aircraft engines. Batchelor felt a small streamliner like the MG Ex-135 was the way to go. He had also studied the big German Auto Union and Mercedes record cars. The engine would be the same record-holding V8-60 but the tread was narrowed to lessen the frontal area.

The completed chassis was taken to Valley Custom in Burbank where Neil Emory, one of the finest early custom craftsmen, was beginning to work with aluminum (the headrest on Alex’s tank was one of his first projects) and agreed to work on the streamliner. To keep costs down, the car was designed as a flattened oval with no compound curves between the front and rear bulkheads. Emory would fabricate the complex nose and tail working at night, and Alex, Batchelor, and their friends would do the rest. Their heart was in the project so they just kept working until it was right.

Early test runs at El Mirage ranged from an easy 135.54 maiden run to 142.40 mph with a two-way SCTA record run of 138.74 mph. Keep in mind this was accomplished over 70 years ago with a 156ci Flathead Ford. When the first Bonneville Nationals were held in August, the SO-CAL Speed Shop Special resplendent in white and gold was the star of the meet.

The Oct. ’49 issue of Hot Rod magazine put it this way:

“The first running of the Bonneville National Speed Trials was assured of success when the team of Alex Xydias and Dean Batchelor assisted by Bobby Meeks fired their So-Cal Special Streamliner through the 5-mile course at a speed of 187.89 mph. Running the car with its usual Edelbrock-equipped Ford-60 engine through the early days of the weeklong meet, the boys came out on Thursday and set an average speed of 156.39 mph on the two runs in opposite directions.”

Read More: 1950 Ford F-1: Iconic Style With 4BT Diesel Power

Edelbrock employees Meeks and Don Towle told Edelbrock how impressed they were with the car at dry lakes meets. Alex, of course, had been an Edelbrock dealer for some time and it was suggested that an Edelbrock-built Mercury should be tried in the car. This at first panicked Batchelor because he was sure the Merc would have at least a hundred more horsepower than the little 60 the car was designed around. But he eventually warmed up to the idea.

Hot Rod continues:

“Then, rushing the car back to Wendover 6-1/2 miles from the course, the team switched to an Edelbrock-built Mercury engine of Class C dimensions and returned the same day to continue running.

The first trial run with the C engine netted a warm-up speed of 154.90, which assured them of the balance and handling of the car.

Naysayers immediately concluded, ’That thing won’t go any faster with a Merc than it did with the 60—that’s as fast as a Streamliner will go.’”

On Friday morning, Batchelor made a full-throttle pass while Meeks waited for the speed at the timing stand. After what seemed like hours with no announcement of the speed, Meeks inquired about the delay and was told Batchelor had gone off the chart. Times had only been calculated to 180 mph and Batchelor had exceeded that so the exact speed would have to be calculated by hand.

Immediately the critics were silenced and the crowd around the timing stand wondered had he gone 181 or 201? The answer was 185.95 mph or over 20 mph faster than any car had ever gone in dry lakes competition! Alex hadn’t driven the car since it was a belly tank and later in the day buzzed the course at 187.89 mph to reaffirm the earlier feat.

Hot Rod continued:

“By far the most outstanding car, not only in performance but also in its striking appearance as well, the little flat streamliner was the smoothest-running machine on the course. Never in all its runs was a waiver or bobble noticed. In the traps on the record run, at close to 190 mph, both front tires lost their treads. The car continued on its way straight down the course and was brought to a smooth stop by driver Dean Batchelor. The ribbed racing-type tires, guaranteed only up to a speed of 175 mph were completely bald and came through the run with perfect carcasses intact.

The run, fortunately, proved that Indianapolis-type racing tires are the only qualified equipment for extreme high-speed runs. However, nobody, least of all Alex and Batchelor, expected to reach the speeds that they attained. Running for records on Saturday the car turned 193.54 on the north run and returned at 185.95 for a Bonneville record average speed of 189.475 mph.”

The performance earned Alex and Batchelor the Tooele (Utah) Chamber of Commerce award for the Best Designed Car as well as the Grant Piston Ring Trophy for Top Speed of the Meet and Diametric Balancing award for top two-way average. (The coveted Hot Rod magazine trophy for Top One-Way Speed of the Meet was not created until 1950 and So-Cal’s 1949 speed was added retroactively). Amazingly, the two records by the So-Cal Special were the two fastest of the meet. No other entries made a two-way run as fast as the little V8-60, much less the Merc! In just 10 months, Alex and So-Cal scored their second Hot Rod cover. Ads from Edelbrock and, of course, So-Cal celebrated their achievements.

After Bonneville, the ‘liner fitted with larger 6.00×16 Indy tires and new wheel housings, made two more lakes meets with the Merc installed, setting an El Mirage record of 174.33 (178.92 mph one way) and then a month later turned a 180-mph two-way average.

At the first lakes meet of the season in May 1950 with the V8-60 back in place, Batchelor made a run of 152.28 mph. Later, on a return record run with a heavy crosswind, the car got broadside to the course, barrel-rolled once, landed back on its wheels and spun to a stop.

Later, Batchelor recalled:

“I had the wheel turned to the left, compensating for the crosswind coming from the left. The wind let off, I’m already corrected and all of a sudden it’s going around. I turned the wheels the other way and the car kept going sideways until it got broadside to the course. The right-side exhaust pipe dug into the ground and flipped it over a complete 360 and landed on the wheels … I missed several chances to do myself in. We had no rollbar and no shoulder harness. If the car had landed upside down, I’d have lost my head, and if I hadn’t kept my feet up, I’d have lost both legs. I quit driving right there.”

The belly pan had been riveted on in normal aircraft practice and tore loose in mid-air. Fortunately, Batchelor drove with his feet wedged against the front cross member (all controls were hand-operated), which miraculously kept them in the car. Fortunately, it landed so hard that it broke both front motor mounts, shearing the Kong ignition and stopping the engine. Batchelor was knocked unconscious, but his only injury was a severe cut over the left eye caused when his head was thrown forward on impact and his war surplus goggles went up under the helmet.

For the rest of his life, he was distinguished by a left eyebrow, perhaps a 1/2-inch higher than the right. He went on to design two more outstanding Streamliners, the Hill-Davis (City of Burbank) and the Shadoff Special.

Read More: Pieced Together ‘34 Ford Highboy Coupe

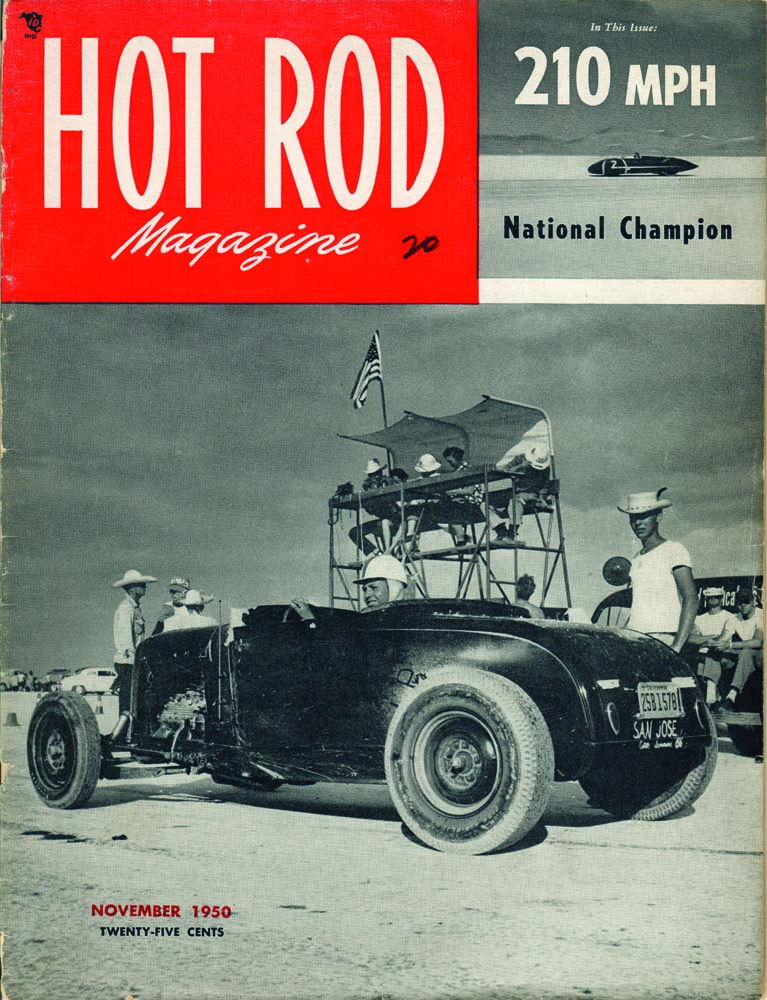

The rest of the summer was spent repairing the badly damaged ‘liner and preparation for Bonneville. The job took so long that there wasn’t time left to paint, so the primer coat was color sanded and waxed and the numeral “2” hand-painted by now-former driver Batchelor. Bill Dailey, a friend of Alex’s, and Ray Charbonneau, a friend of Batchelor’s, both wanted to drive the car after Batchelor’s retirement, so it was agreed that they would trade-off. Once again, the So-Cal Special was fastest in the land with a one-way run of 210.8962 and a two-way Class C record of 208.927 mph, eclipsing Ray Keech’s 32-year-old record.

Alex and Batchelor had again won the Hot Rod Magazine Top Speed trophy—but just barely. The Kenz “Twin-Ford Special” from Denver (later the Kenz and Leslie Special) was actually first to the highly coveted 200-mph mark, accomplishing the feat on a two-way D/Streamliner record run of 206.504 mph. The Kenz fastest one-way speed was 210.773 mph. At the end of the week, So-Cal was fastest–less than a quarter-mile per hour! It was simply the fastest hot rod in the world.

In February 1951, Alex and Batchelor were invited to participate in the NASCAR Speed Trials at Daytona Beach, Florida. A poster for the accompanying show advertised the little Streamliner as the “Fastest Car Ever Built in America.” Batchelor couldn’t get time off from Lockheed so Alex, Keith Baldwin, and Bill Dailey made the trip. Hot Rod magazine offered modest sponsorship. Alex later joked with Petersen that his sponsorship money “ran out at about Blythe” (a distance of 230 miles from Burbank).

In any case, the ‘liner was lettered and the team posed for photos along the Los Angeles River bank showing off the new signage as well as the full plexiglass canopy that had been added. East Coast-based Speed Age magazine was by then in its fifth year of publication and firmly entrenched with NASCAR.

When they heard a Hot Rod magazine Special was coming to Daytona, they protested the appearance on their turf–er, (sand) so strongly that NASCAR officials insisted Hot Rod be painted over with SO-CAL except for the left side, which would be toward the water and away from the spectators. Politics even reared its ugly head seven decades ago.

Although the full canopy gave additional streamlining, the roughness of the beach held the early efforts to 122 mph. On the fourth day Dailey’d had enough of tiptoeing across the beach and really got on the gas, at an estimated 150 mph plus, a soft spot in the sand and/or a crosswind took over and the car flipped, went end over end for 1,000 feet, and was destroyed. Dailey barely escaped with his life and suffered a broken shoulder, a fractured skull, and a severe concussion. He remained in a coma for nearly a month but survived.

Ironically, Russ Catlin, Speed Age feature editor, also reporting in the Daytona News Journal, wrote, “I saw in a matter of a split seconds the complete demolishment of the most beautiful speed creation ever built in America.” The only photos of the wreck were shot and published by Don O’Reilly, Speed Age’s editor and publisher. The car that l had less than two years before had revolutionized the concept of amateur speed trials was no more.

The engine, with its three carbs broken off, was returned to Edelbrock; the tires were sold to Northern Californian Al Dal Porto for his beautiful modified roadster and the quickchange was sold to Ray Brown and Mal Hooper. What was left was sold to a junkman for $4.

In 2011 Detroit hot rodder, Ridler winner, and incredible fabricator Dan Webb, with the assistance of his daughter, Ashley, son-in-law Corey Taulbert, and metal man extraordinaire Craig Naff, built an exact replica of the streamliner that was the hit of that year’s SEMA show and rightfully won Ford Racing’s Heritage Award. MR

(Editor’s note: Next month we will bring you the “rest of the story” and we are confident you will find it truly amazing. —B.B.)