The Man Behind The Fresno Dragway, Autorama, and Legendary Emperor roadster

By Michael Dobrin – Photography By the Author, the Blackie Gejeian Collection & Tim Burman

Haulin’ north on the 99, November 1967. Headed for the last drag race, a Super Stock showdown between “Dandy” Dick Landy in his blueprinted Dodge Hemi and Butch “The California Flash” Leal in his Coronet street Hemi. The race would run at Fresno Dragway in Raisin City, California.

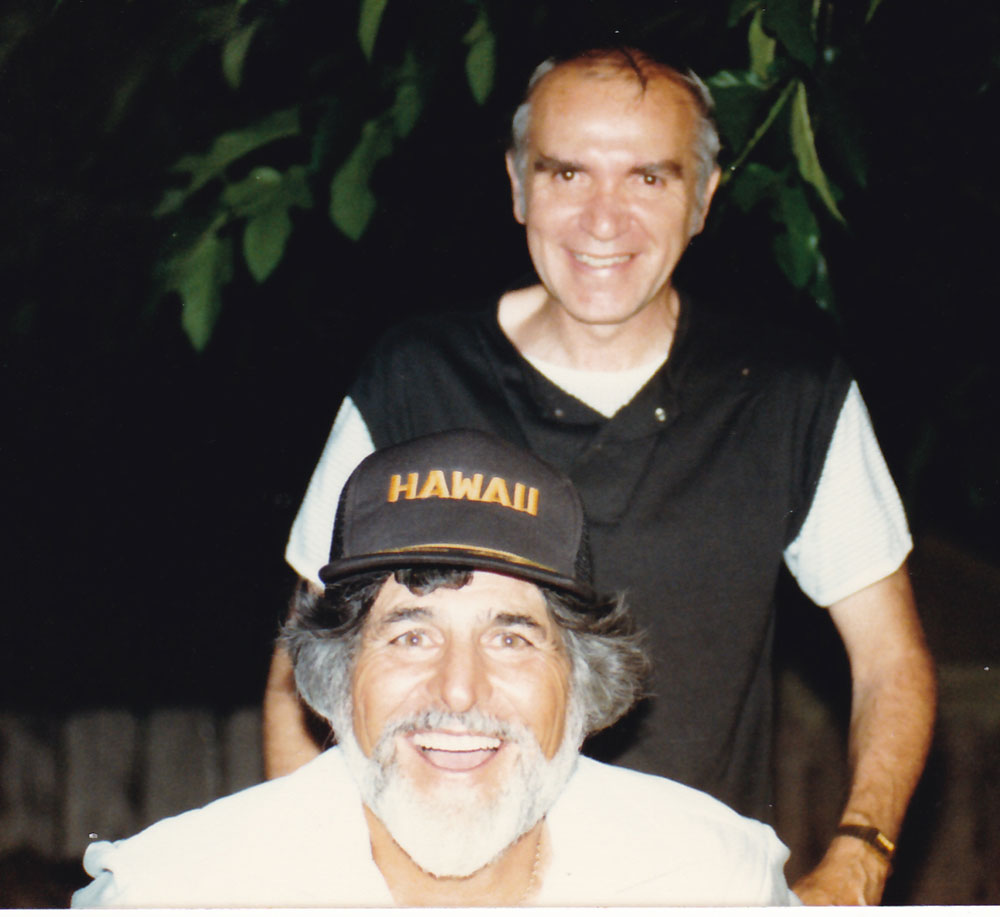

I was ending a long national tour as the advance man for Landy’s Dodge factory racing team, and I had a date with the Dragway promoter, one Michael Gejeian.

Landy handed me his phone number. “Call him Blackie.”

The noonday meeting took place at a rural roadhouse with high ceilings, leather booths, and worn oaken veneers. The place was packed with dozens of working men in working clothes, eating, smoking, playing cards, and drinking red wine out of stubby glasses.

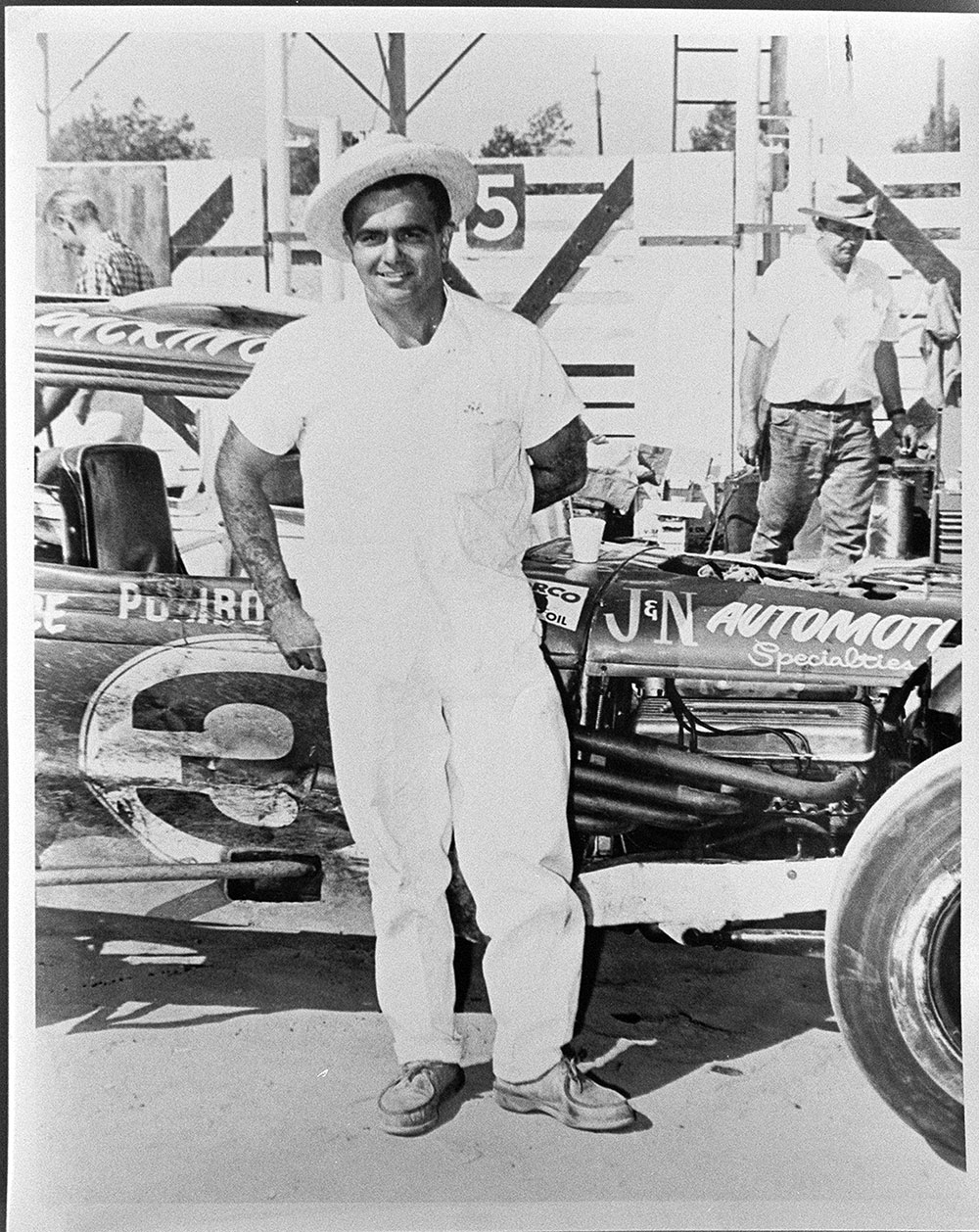

A shimmer of sun cut the dust and a commanding figure walked in; he wore Levis and a torn, mud-streaked T-shirt. His curly, coal-black hair crowned a brow covered with sweat. He was animated; his voice alone commanded the smoky proceedings. He was unlike any promoter I’d met across America. He’d gotten off his tractor and we could do our business tomorrow. Just call. One final impression: he had golden tiger eyes that glowed with ethereal intensity.

When I called, a woman answered. “Is Blackie there?” “Murgadich, he’s not here.” The next day, I began, “So, Murgadich, how’s it goin’?” Oh. Oh. Golden tiger eyes shot a bolt. “You little [expletive], if you ever call me that again, I’ll kill you.” Rule one. Fail to understand Blackie at your own peril. Later, I’d discover that it was Blackie’s mother, Ossanna, who answered, and, yes, she was a prankster. Murgadich (phonetically) is Armenian for “the Baptist.” Her little joke almost got me killed.

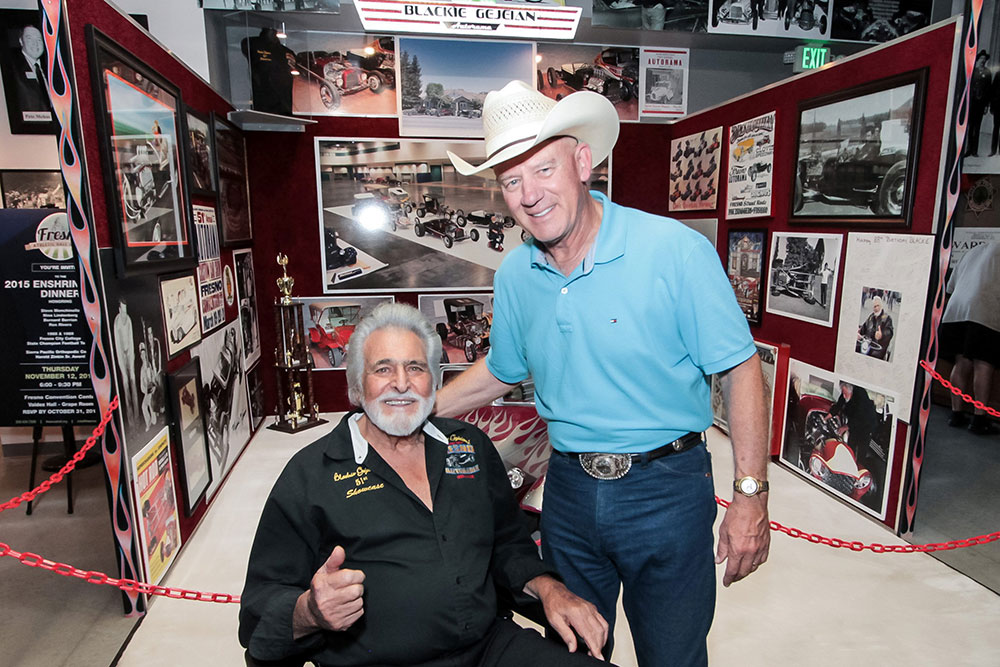

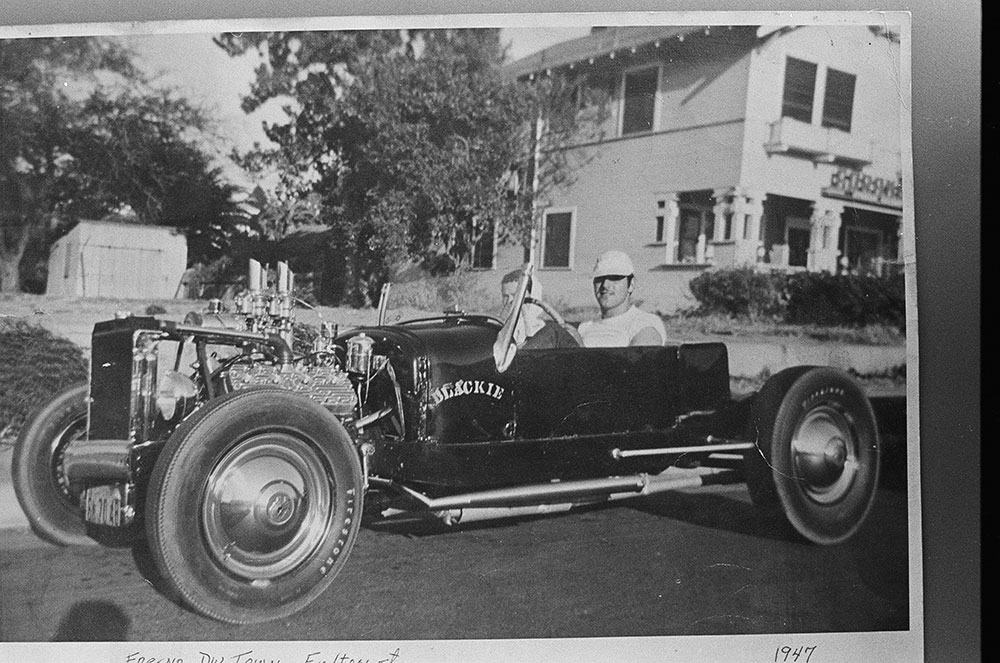

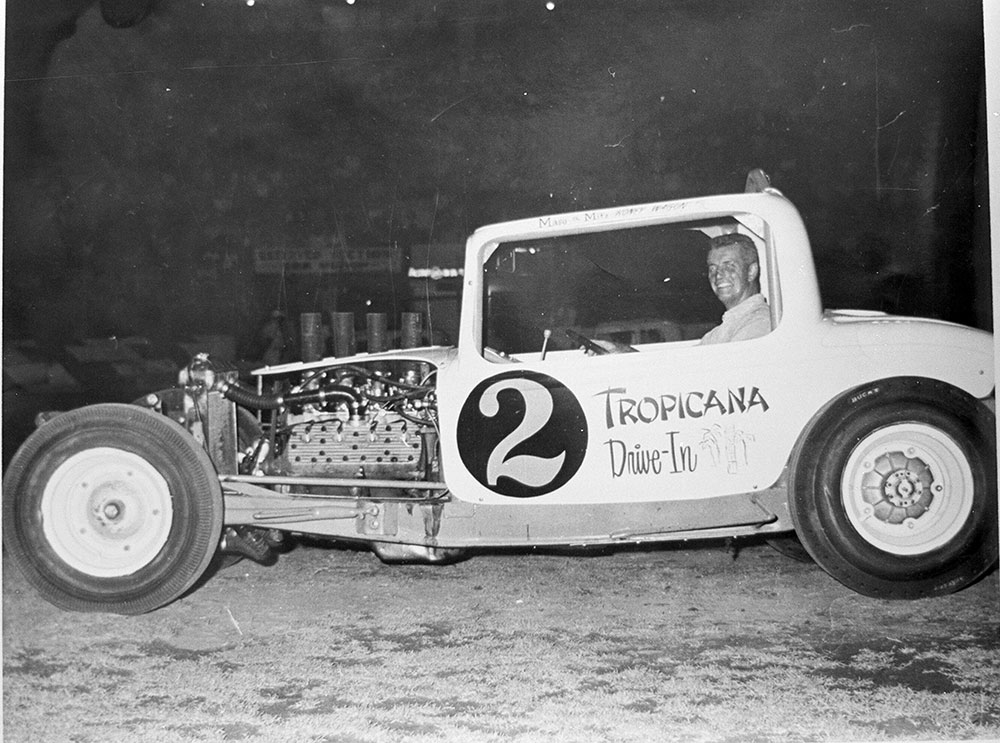

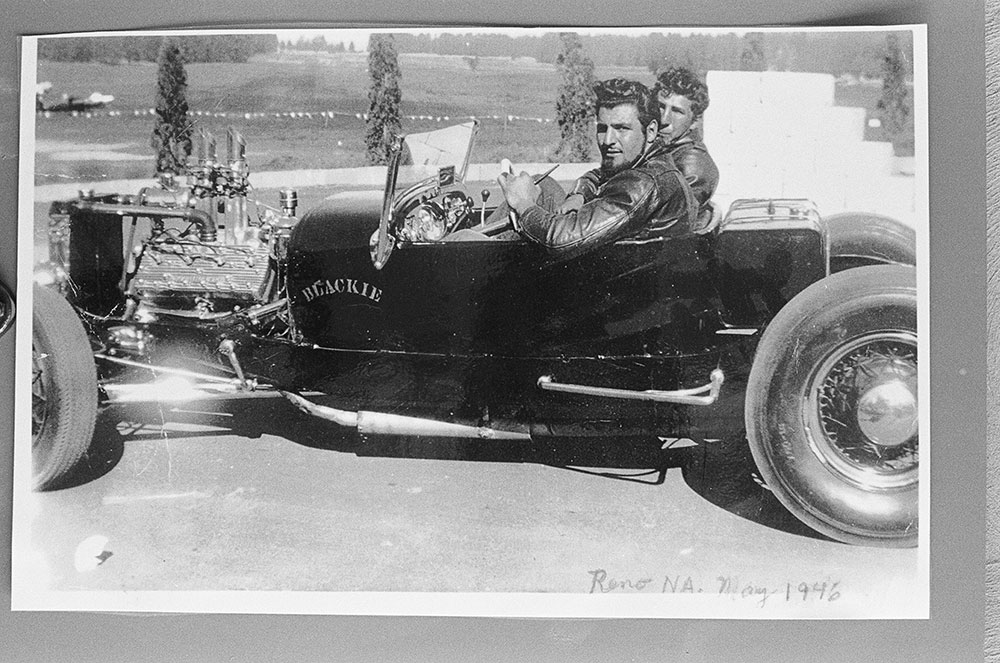

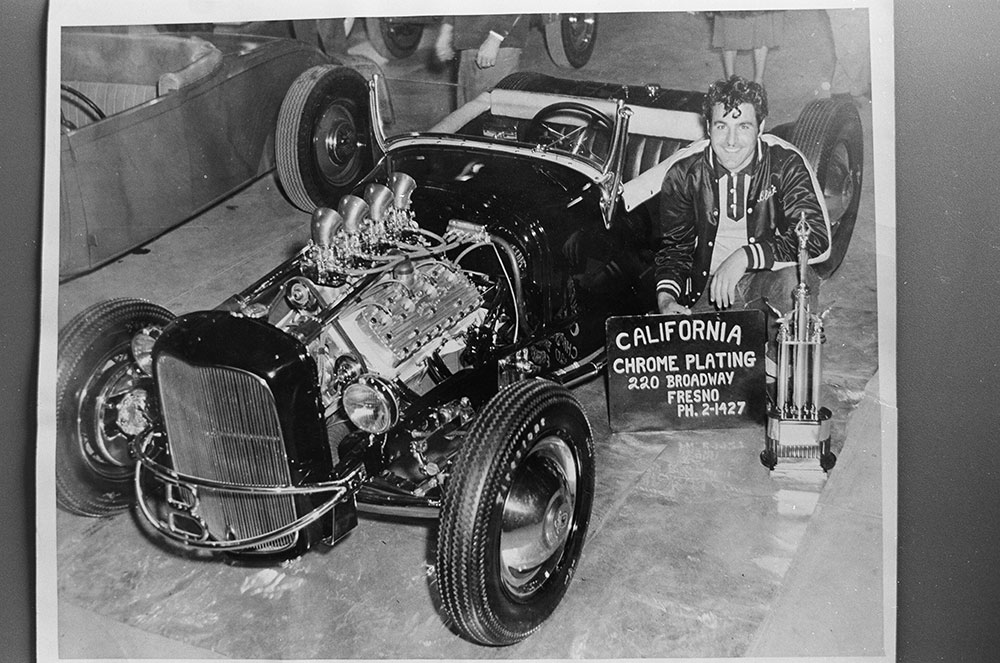

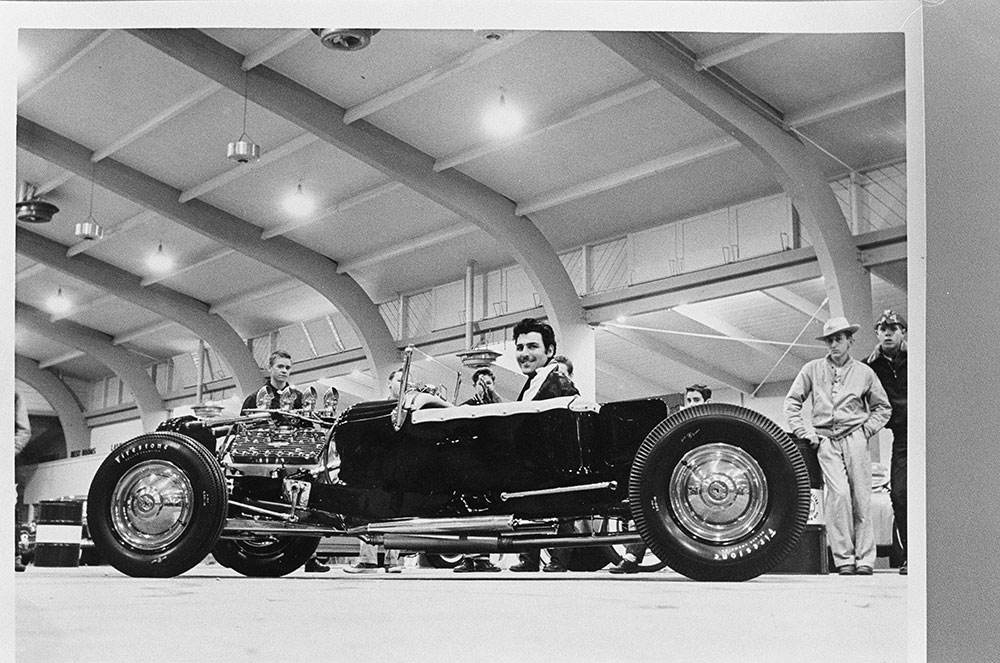

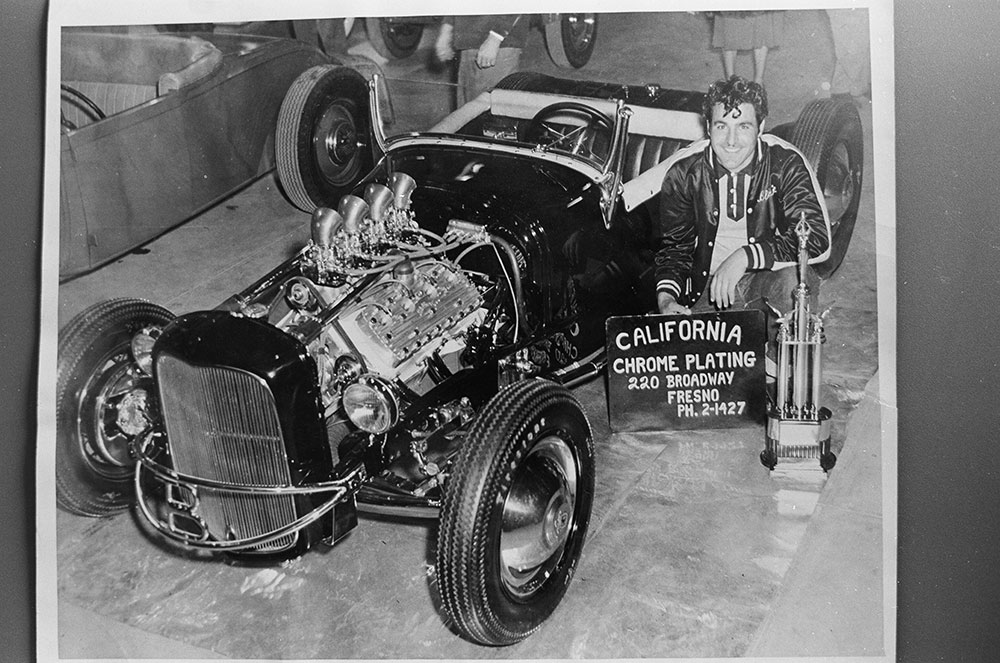

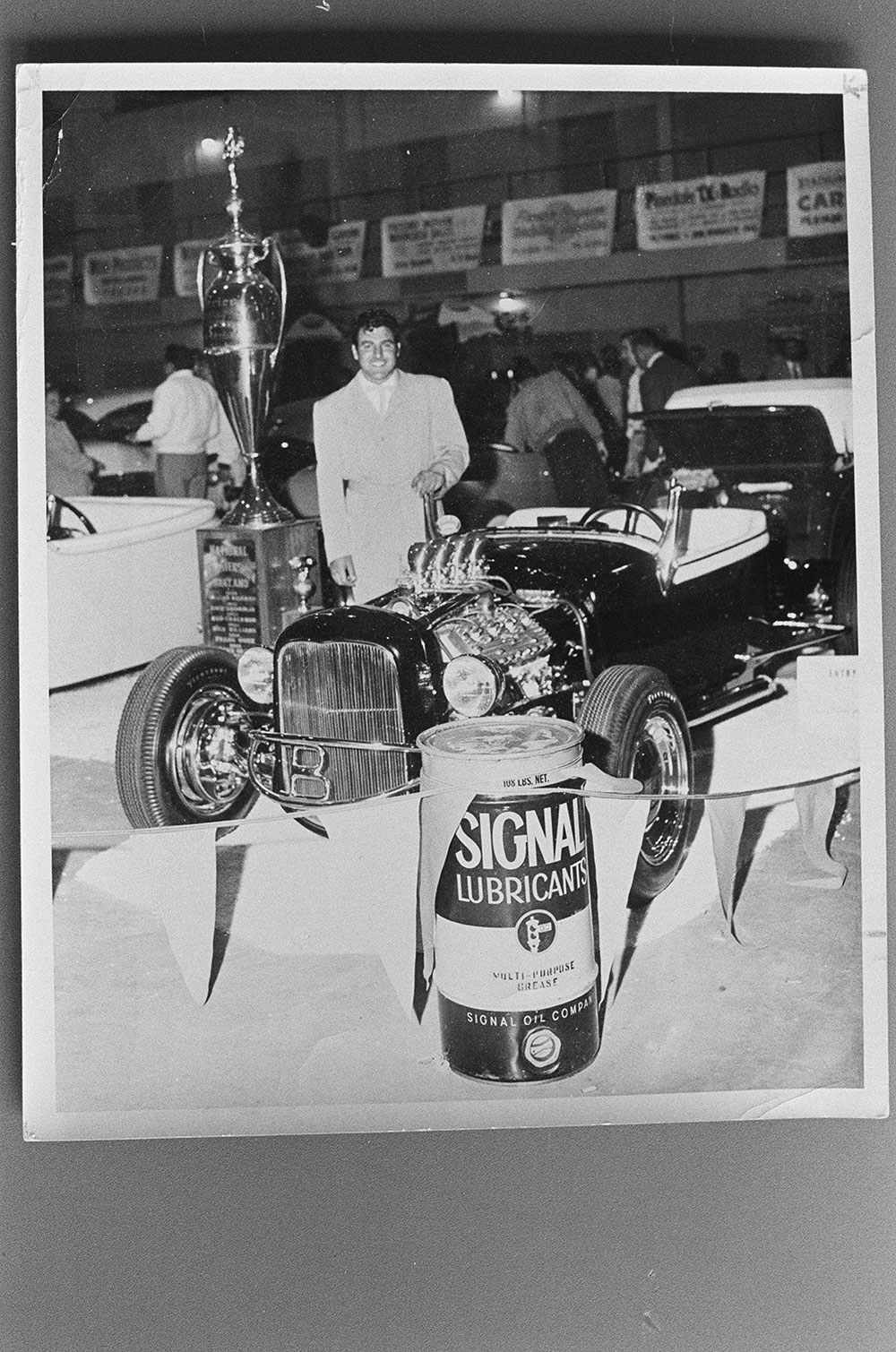

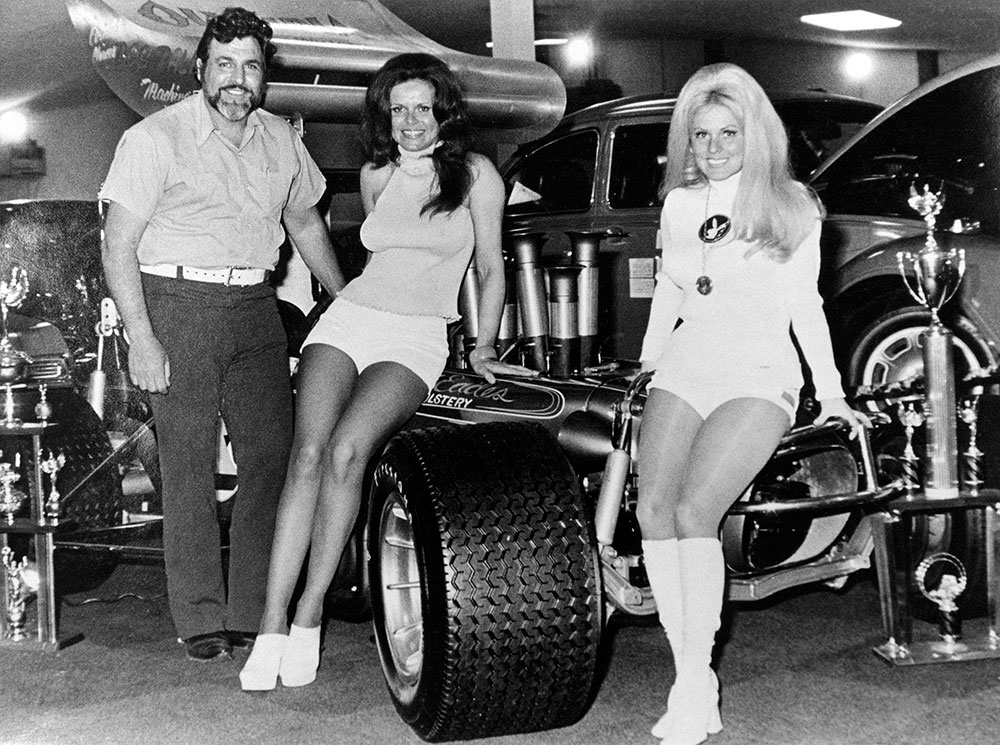

Blackie was a legend, both in his native Fresno and far beyond. For more than 51 years, he produced the Fresno Autorama. It was his show. He scoured the country; he picked the cars, gave the awards, and orchestrated the painterly spectacle. “I was the first showman to color code the cars,” he said. His legacy in Fresno is celebrated by a plaque at the Fresno Convention Center and a permanent exhibit at The Big Fresno Fair. His hand and eye helped shape several landmark show cars, three of which won the coveted America’s Most Beautiful Roadster trophy at the Oakland Grand National Roadster Show: The “Ala Kart” (with Richard Peters and George Barris), only two-time winner (1958/59); the ’29A “Emperor” (with Chuck Krikorian, 1960); and his ’26 Model T Roadster, the “Shish Kebab Special” (1955). The Shish Kebab would stand as a symbol of Blackie’s life of speed, style, and showmanship over seven decades. Chrome undercarriage aside, the T was the real deal: A dead-run hot rod that clocked out many a blacktop racers on Fresno backroads.

Racing History: Alex Xydias The Man Behind The Famous So-Cal Speed Shop

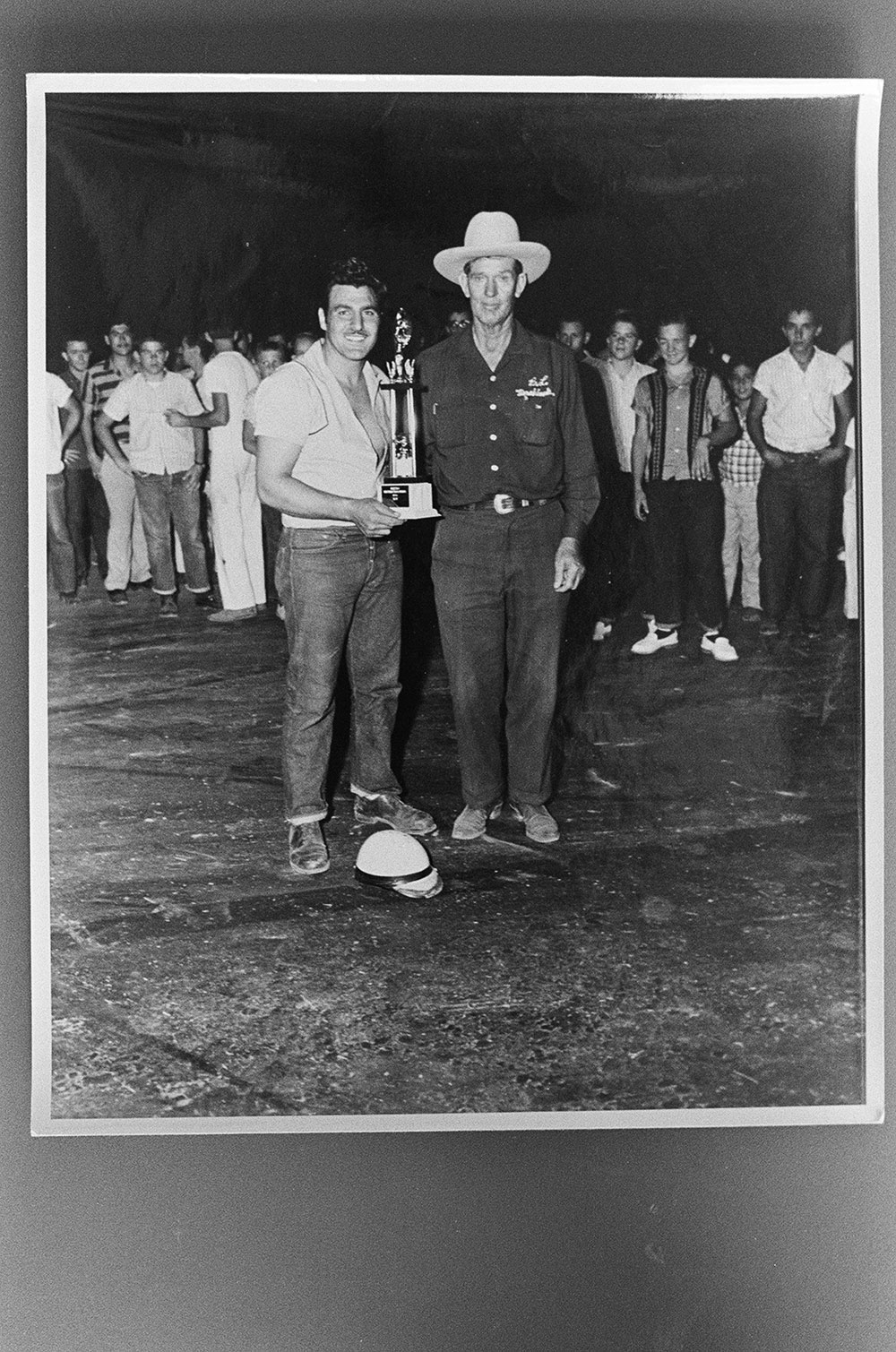

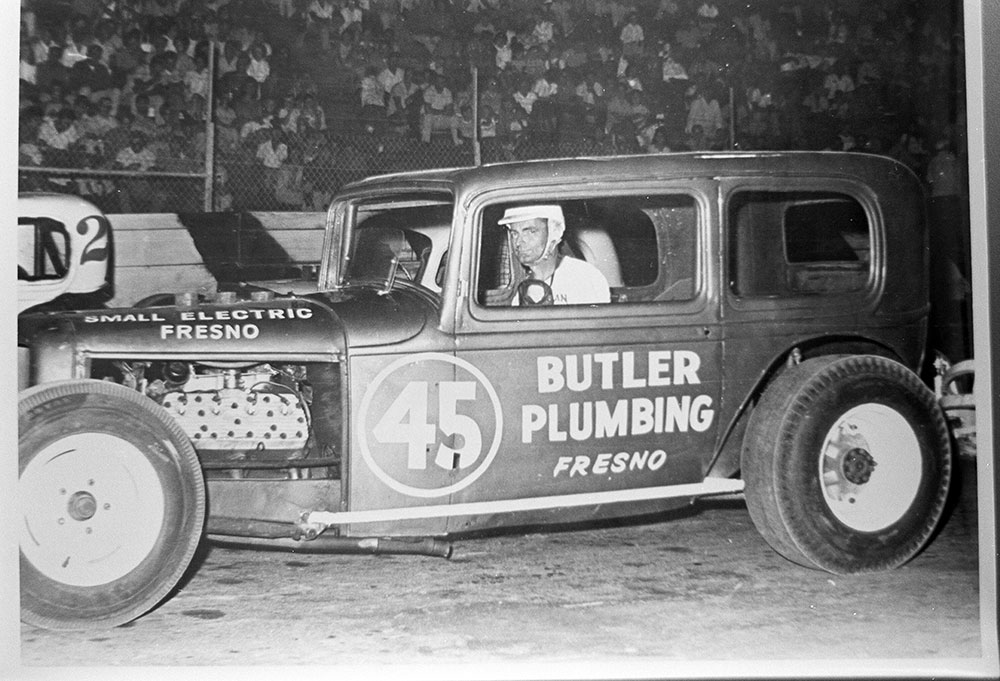

He was a daring and sometimes reckless race car driver whose fiercely competitive spirit in the heyday of Central Valley hardtop racing shaped his sense of showmanship. He learned how to run big events and put the fans first.

He was 90 when his high-revving’ engine finally gave out in September 2016.

Blackie touched thousands and each has a story. There were elements of his life that might shed a timing light on the engine that drove the Blackie legend: his farm, his time racing hardtops, and his Armenian brotherhood in Fresno.

The Gejeian ranch, a 40-plus acre vineyard near Easton, was in the family since 1909, when a first wave of Armenian immigrants came to the Central Valley. His parents fled the Armenian genocide after World War I. The immigrant experience shaped Blackie’s early life. He remembered his large, extended family at the ranch house; grandparents, cousins, uncles, and aunts, and the gatherings on the veranda for music, food, and wine when the heat of the day began to recede. Writer William Saroyan would come out to talk life, people, and Armenian soul.

“He was truly a farmer,” Carol Cusomano of Clovis says. She and her husband, Joe, were top International Show Car Association show car winners; she staged the world class tribute to Blackie at Fresno’s Convention Center in September 2016. In Blackie’s later years, the Cusomanos escorted him to shows, SEMA and rod and custom gatherings.

“On our way to events, he’d talk about the soil, the orchards, the vineyards. He loved the earth,” she recalls.

Eugene Sadoian, “Clean Gene” to Blackie, was a lifelong and steadfast friend. The retired chief federal probation and parole officer, now 87, lives in Las Vegas. He remembers his first encounter at the ranch in 1948.

“So, there I am, meeting the famous Blackie at his headquarters, but even more impressive was his father. Charles wore bib overalls, no shirt, always with a shovel in his hand and no shoes.

“The next time I was out there, Blackie was tearing around like a dirt tracker in his dad’s Model A. He spun and wiped out three rows of vines. Uh oh! Here comes dad with shovel in hand, storming barefoot through the vineyard. Blackie took off and didn’t come home that night.

For a time, Ossanna had a psychic-hypnotist, Hyrkos, living at the ranch. According to Sadoian, his psychic powers seemingly passed to Blackie’s daughter, Diane.

Blackie’s day began at 3 a.m. when he fired his tractor and began tilling the vineyard. Then onto business, his show, track preparation, race car prep, racing. Restart. Seven days a week.

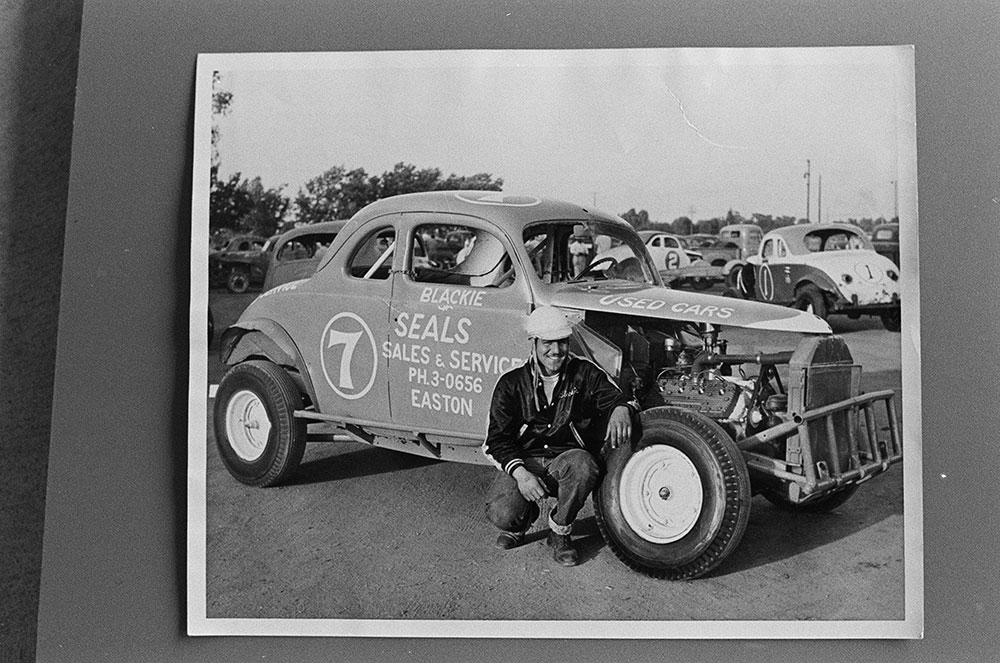

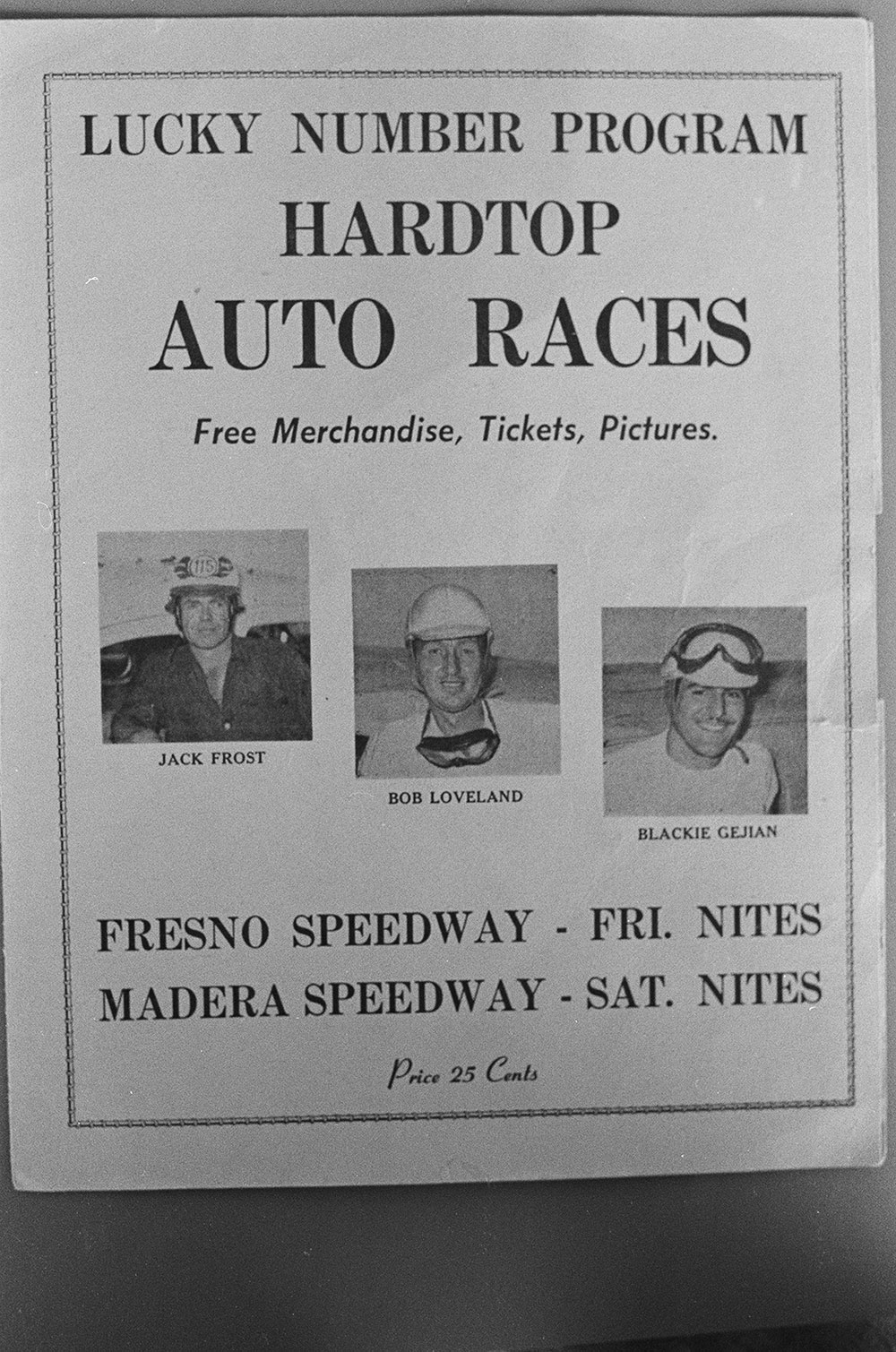

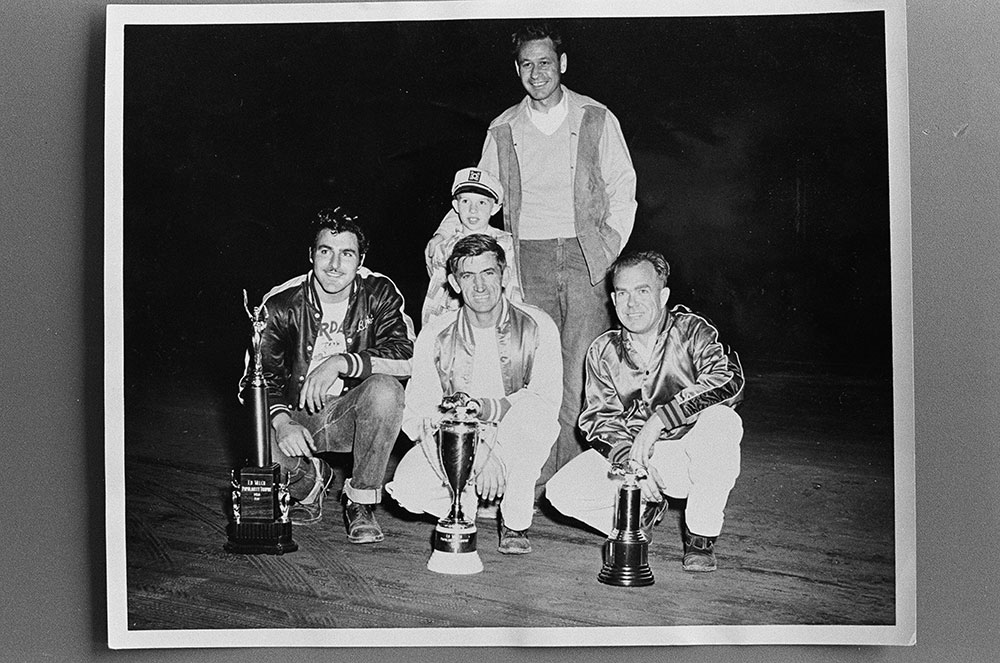

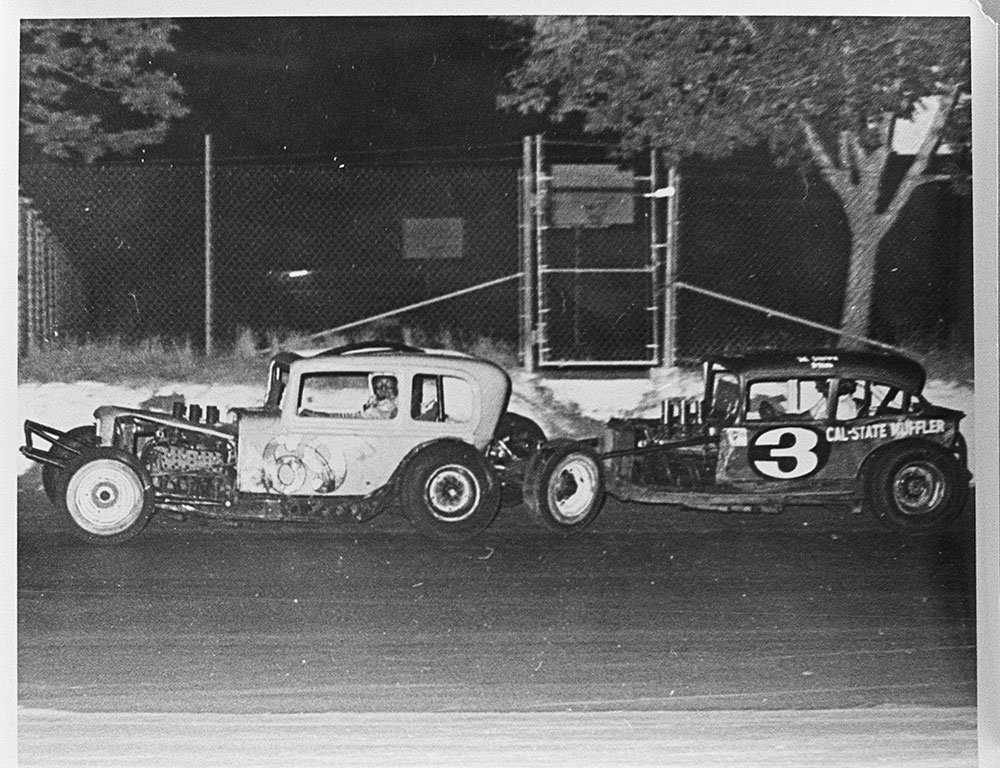

“He came along to rival Billy Vukovich as a favorite son,” recalled late circle track racing promoter Bob Barkhimer. In 1949, “Barky” and fellow midget racer Jerry Piper, organized an intense Central Valley hardtop racing show on half- and quarter-mile dirt and paved tracks from San Jose to Clovis.

“Blackie drove an orange Ford coupe, (he) was a handsome devil with flashing eyes and black, curly hair . . . he had charisma galore, waved his arms all the time, and was excitable on and off the track. The fans loved him.”

Sadoian recalls a lot of those races. “He polarized the crowd. He brought them out to races even if he played the villain. I always worried because as a fastest qualifier, he started at the back. When the flag went down, he’d charge fearlessly through the pack; crash or no crash, he’d win. He put flaring bellows on his tailpipes and the noise alone would fire up the crowds.”

Next we’ll look at Blackie’s growing organizational skills in producing and promoting motor racing events, his grand Fresno show, and his willingness to assist other motoring enthusiasts, all in part driven by his hard charging Armenian motoring brotherhood in Fresno.

Read More: Award Winning Metal Work: 1934 Chevy Roadster

“There’ll never be another Blackie,” Fresno’s late Kenny Takeuchi, the dean of Central Valley track announcer, said. In an earlier interview before his death in 2019 at 92, “Tak” recalled his four decades as track announcer, historian, media manager, and statistician as well as his respect for Blackie’s diligence and attention to detail. “We had a four-track modified circuit. Friday night we’d race at Kearney Bowl, Saturday at San Jose, a Sunday day race at Altamont, and then close the series Sunday night at Clovis.

“We had 60 cars, enough for A, B and C main events,” he said. “Blackie’s biggest fear was that there wouldn’t be enough cars and drivers left after three races; we raced the same cars, pavement, dirt, didn’t matter. Officials from San Jose and Altamont would have to high tail for Clovis. But we were good. We arrived on time and Blackie’s show was well run, well officiated, everyone in and out on time. The track was well prepared when we got there—no waitin’ around.

But when he was upset his voice would carry a mile. That was time to clear out. Blackie was giving with counsel to anyone who loved cars as much as he did. “He was a teacher and mentor for Rick (Perry) and I after we took over the SF and Oakland events after Don’s (Tognotti) [death],” show manager, promoter, announcer, video, and voice impresario George Hague says.

Writer-historian and Pebble Beach judge Ken Gross remembers, “Blackie was unique. He was a perfectionist in every way. I can’t name too many people who had that perseverance, influence, and sheer energy.”

In 1997 Gross guided the Pebble Beach Concours judging committee to a show class for American hot rods and in 2001 Blackie entered the fully restored “Shish Kebab Special.”

“He wanted to win,” Gross recalls, “but got Third. He was hurt, always the quintessential competitor. But he’d taken liberties by reinstating some flaws. He’d even recreated some crooked seams in the T’s original leather.”

NHRA historian and curator Greg Sharp knew Blackie more than four decades. “He was bigger than life. He loved it all, racing, roadsters, shows. He was irrepressible, but he suffered a lot of medial setbacks in later years.”

There is no national or ethnic handle on motorsport excellence. But in Fresno in the late ’40s and ’50s, there was an all-consuming Armenian commitment to speed, the motoring arts, competition, and thriving automotive businesses.

Blackie set the pace on the streets of downtown Fresno. He idolized USAC promoter J.C. Agajanian and was a feted guest at “Aggie’s” 100-mile invitational Open Championship at Ascot Speedway. Ed Iskenderian was born in Cutler over a century ago, but his dad went broke farming and they moved to L.A. Freddie Agabashian, from nearby Parlier, went to Oakland to be nearer the big car action. Harold Bagdasarian left Fresno to orchestrate his own car shows in Sacramento and Oakland.

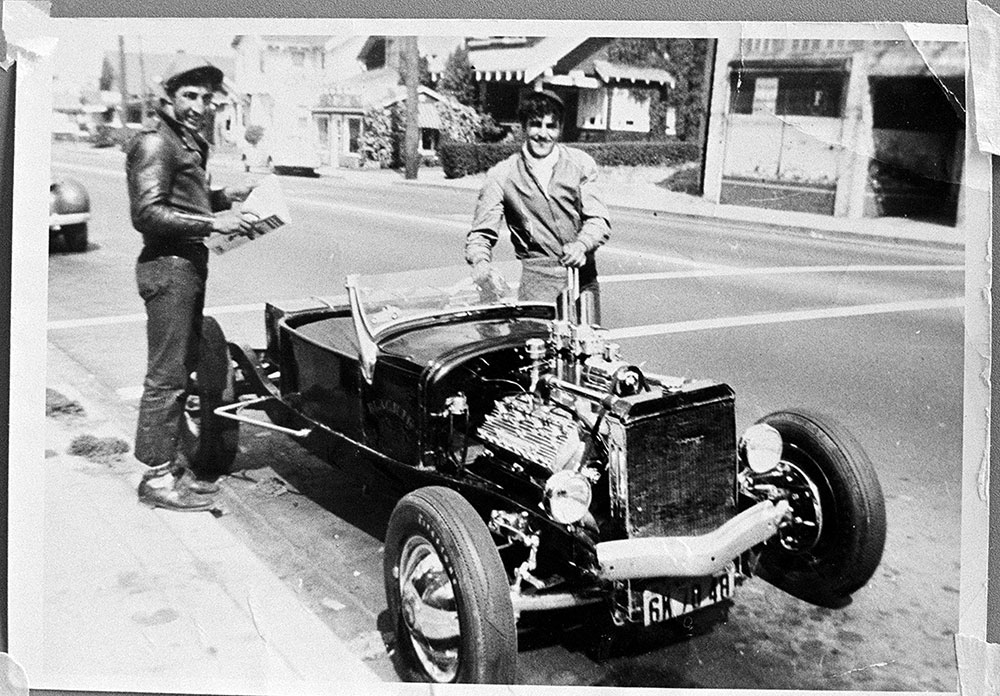

Eugene “Clean Gene” Sadoian remembers the racing brotherhood. “Blackie’s cousin, Richard Shirinian, had a candy orange A roadster, a channeled show and drag car. He bought the body and frame from Paul Soligian, who supplied orange paint for Blackie’s racing hardtops. Smokey Hanonian was the local Bowes Seal Fast distributor and was Blackie’s sponsor as well as a flagman at Clovis and Kearney Bowl. Mike Garabedian painted my ’34 and Blackie’s roadster. Sammy Arakelian was always hanging out at Blackie’s with his severely chopped blue ’36 Ford sedan, chrome dash, blue instruments. Ed “Shrimp” Koomjian ran Eddie’s Speed Shop. Joe Boghosian is now retired. He built most of Dan Gurney’s DOHC Ford engines for winning Coyote teams. His race engines powered everything fast–drag boats included.

Racing History: Record-Breaking Race Team, Filmmaking, and Legacy

“Joe called Blackie sev shun, Armenian for ‘black dog’. There was no word we knew for fox; he just became black dog,” Sadoian says. “Fred DeOrian was Vukie’s mechanic. John Siroonian, owner of Western Wheels, had a beautiful collection of deuces. Won the big trophy at Oakland.”

Why did so many young Armenian men in Fresno get involved with hot cars, performance, and showmanship?

Dr. Barlow Der Mugrdechian, head of Armenian Studies at California State University, Fresno, didn’t have a specific answer about motor racing, but said, “Armenians will take a challenge. They’re bold and daring. It’s a cultural thing. They’ve heard about the old country and built this into their American identity. William Saroyan wrote about their willingness to take chances.”

Blackie took chances—on the tables, on the track, and in life.

“The competitive spirit is in the Armenian DNA,” John Alkire, former CEO of the Big Fresno Fair and now curator of the Fair’s history museum, says. He engineered a permanent exhibit in the museum about Blackie’s life in Fresno. The Gejeian diorama is crowned by a bronze bust of Blackie, one created by Fresno’s Debbie Stevenson.

“This was racing at a different level,” Alkire continues. “They had rough beginnings; they’re survivors. I was the CEO at King Speedway in Hanford (California), and the Armenian drivers were the most competitive, the most aggressive.”

Hoss! Blackie knew thousands but remembered a few names. Hence, you were ‘Hoss.’ “Blackie, what was her name?” “Hoss!” And the golden tiger eyes would crinkle with joy.

When this reporter helped produce the Oakland Museum of California’s “Hot Rods and Customs” exhibition in 1996, Blackie generously loaned his Emperor roadster as a center stage feature car along with other AMBR winners in the museum’s Great Hall—plus, of course, the AMBR trophy itself. Midway through the press gathering at the show’s opening, Blackie sidled up, “Hoss, it’s too quiet in here.” I knew what he was up to and knew there’d be no stopping him. He returned with a battery, hooked it up, and fired the Caddy, open chrome headers, and raw petrol fumes. The roar was deafening; it set off fire alarms downtown. A museum lady came running down the stairs, crying, “Make it stop! Make it stop!”

She never knew, of course, that there was no stop in Blackie’s life. MR