An LS Engine Swap is More Than Just That

By Ryan Manson – Photography by the Author

Engine swaps have been happening long before the first 265ci V-8 rolled off GM’s production line. It would be hard to argue that an engine has been swapped into more cars than the venerable small-block Chevy, but its baby brother, the LS-series engine, has got to be pulling a healthy spot in Second Place. Poke your head under the hood of any Tri-Five, Camaro, Chevelle, or other classic Chevy at the local cruise-in and you’re likely to be face to face with the same engine that powers your neighbor’s contemporary Silverado. The LS swap has become commonplace, and for good reason.

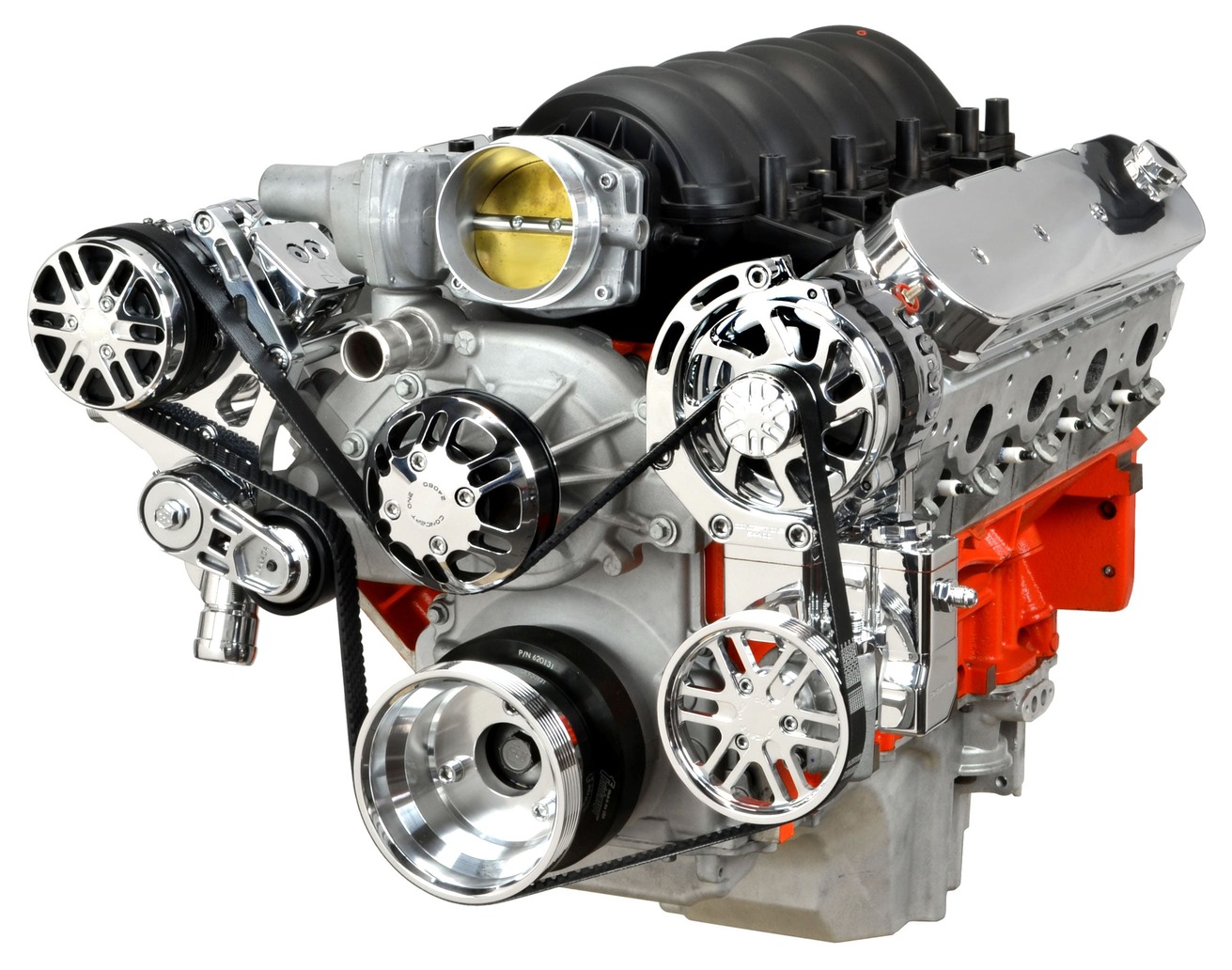

For starters, the LS-series engine is similar in size, with the old small-block being slightly longer due to the extended snout of the water pump to facilitate a mechanical cooling fan. The LS, in comparison, is a few inches wider due to its cylinder head design. Its shorter length, in addition to the lack of a distributor to foul the firewall, makes placing an LS engine a more variable affair. Additional clearance at the radiator side for accessory or electric fan clearance can easily be accomplished since the bellhousing area of the block can be slid further rearward into the firewall thanks to the additional clearance provided by the aforementioned lack of distributor.

Another physical benefit provided by the LS-series engines are weight. While materials varied throughout the years, a fully dressed LS engine with an aluminum block, cylinder heads, and composite intake manifold could yield a weight that is tens if not hundreds of pounds less than a first-gen iron small-block. A modest weight reduction over the front axle centerline can result in a more balanced distribution of weight and an overall better-handling car. That’s a huge step in the right direction when accompanied by similar improvements in the brakes and suspension department to turn that heavy Chevy into a canyon-carving cruiser.

More Reading: Assembly of Chevrolet Performance’s 1,004hp ZZ632

Size matters aside, the performance aspect of the LS engine family is truly the elephant in the room. Producing power numbers from the factory floor that meet or exceed the highest tuned, tightly wound ticking time bombs from the ’60s, GM’s engineers pushed the design elements of the LS engine as far as their computers would allow, resulting in not only some of the highest performing small-blocks to date, but some very efficient ones to boot. Thirty years ago, a true, naturally aspirated, 400-rwhp small-block Chevy-equipped muscle car was not a very common sight to see cruising the streets of Small-Town USA. Today, an LS engine built with a decent set of heads, cam, and intake not making 400 hp might be considered an anomaly. And while that vintage stroker spit and snarled while it struggled to stay together, that modern LS engine hums along like a Swiss watch, quietly waiting to unleash its massive power.

And yet while not everyone wants a 600hp, fire-breathing LS engine, performance isn’t the only reason one might choose to make the swap upgrade. Over forty years of technological improvements have been made between the introduction of the first Gen-I small-block and the LS-series engines. Basic similarities in design aside, the modern LS engine has less in common to that original 265 than it does to a Flathead Ford. Computer-controlled ignition and fuel systems result in an extremely efficient, reliable power package. While technically more complex in leaps and bounds when compared to a traditional small-block Chevy, the number of moving parts on an LS engine that are prone to failure are, in conjunction, far fewer. The typical EFI system on an LS engine is much simpler, as far as the moving part is concerned, than a carburetor.

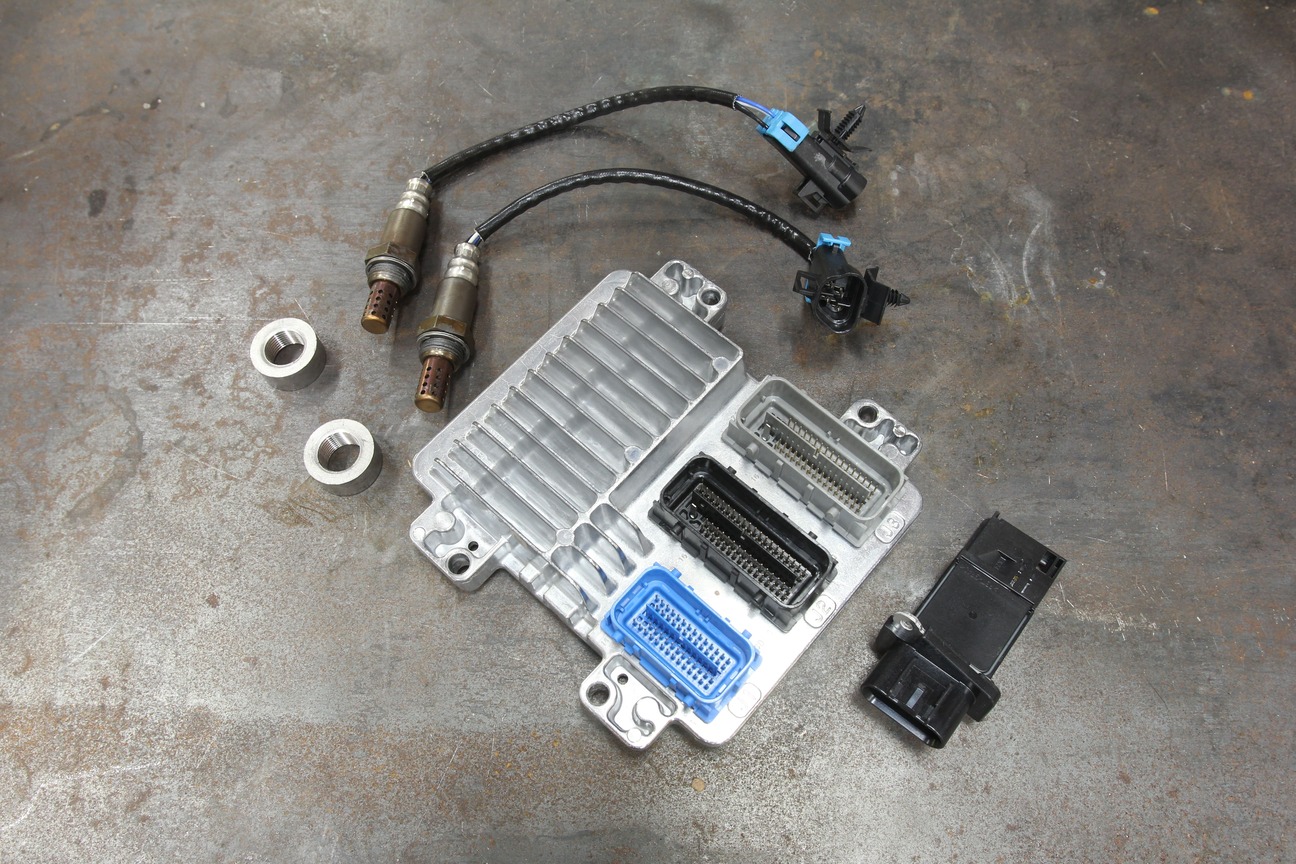

The ignition system is similarly as simple. Comparing the components involved, the LS uses a crank and cam position sensor to send engine information to the engine control unit (ECU), which then transmits that info to each cylinder’s ignition coil, firing that particular spark plug. There are literally zero moving parts in the LS ignition system, aside from the camshaft sensor trigger and crankshaft reluctor wheels, which are part of their respective components. Contrast that to all the ignition components found on a traditional small-block that can be prone to failure and are considered consumable (distributor cap, rotor, points, condenser, and so on) and it’s easy to see that while the LS system is far more complex, technologically, it’s also physically far simpler. This results in a much more reliable powerplant that requires far less owner participation. For those of us who prefer to spend more time behind the wheel than underhood, the reliability that comes with an LS swap is hard to beat.

The efficiency of the LS engine is another benefit that comes with the 40-plus years’ worth of technological improvements. Incorporating a computer-controlled fuel and ignition system results in a much more efficient combustion system, where the ECU can make instantaneous changes to the tune to keep the engine in an ideal state. This results in improved fuel economy, oftentimes into 20-mpg territory, something that old small-block could only dream of. Coupling that with an overdrive trans, whether it’s a manual or an automatic, only further helps promote the LS’s ability to master its efficiency.

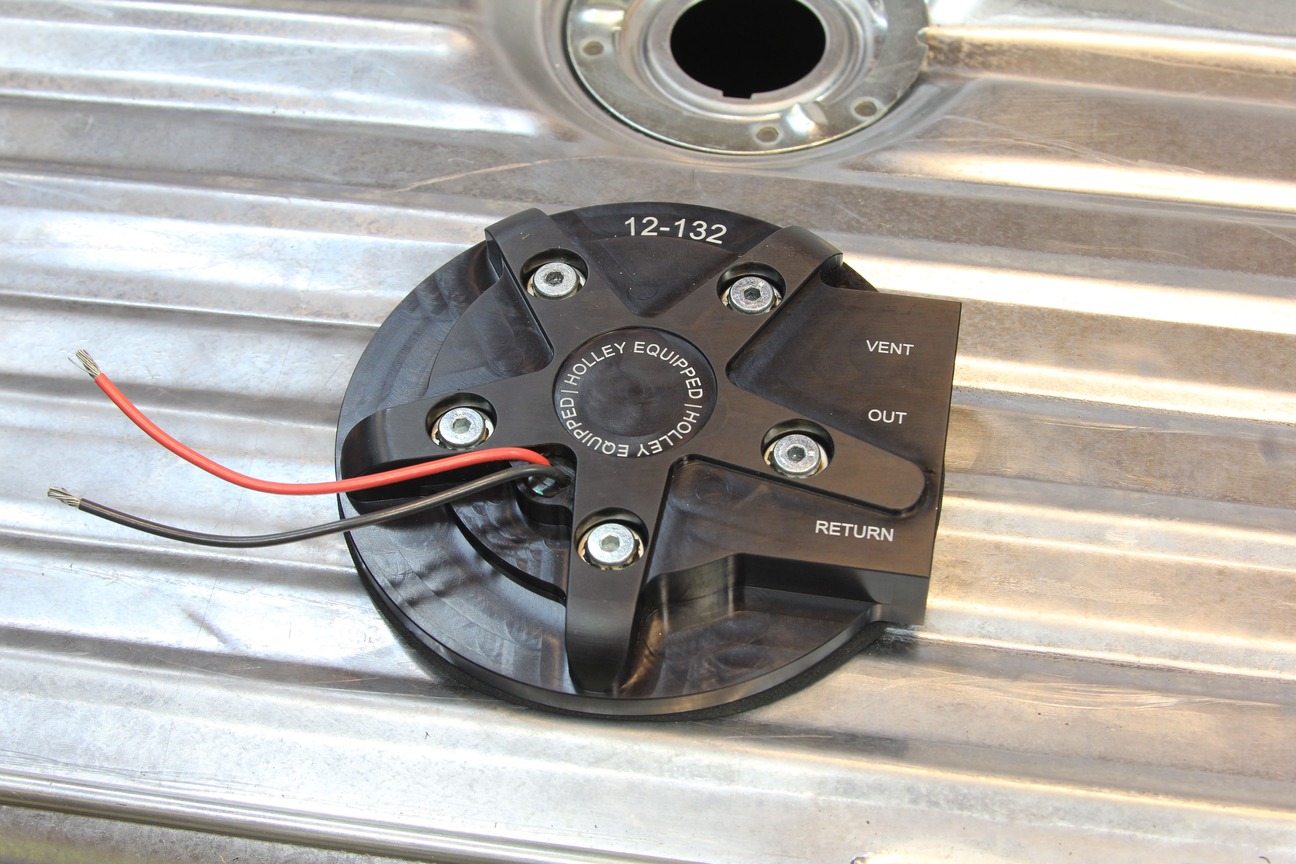

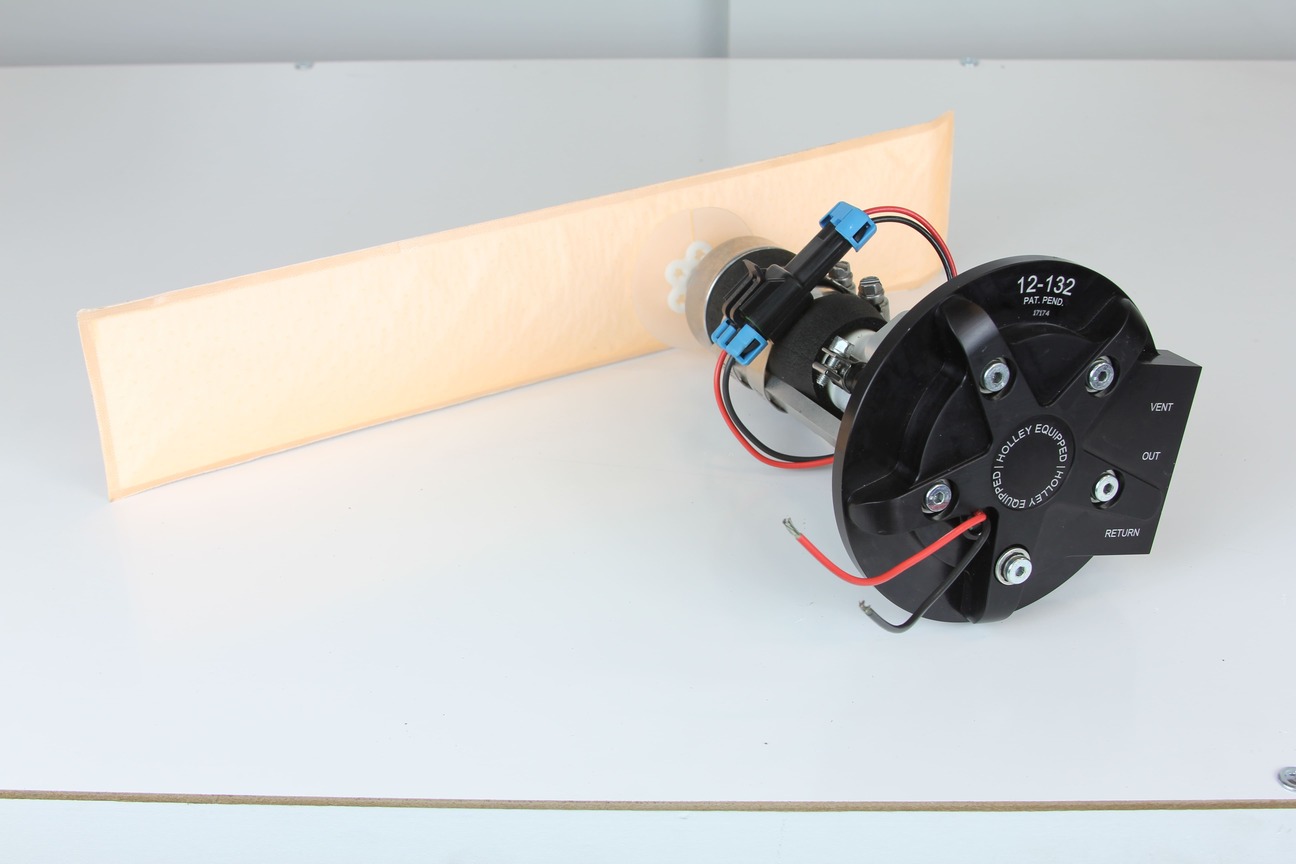

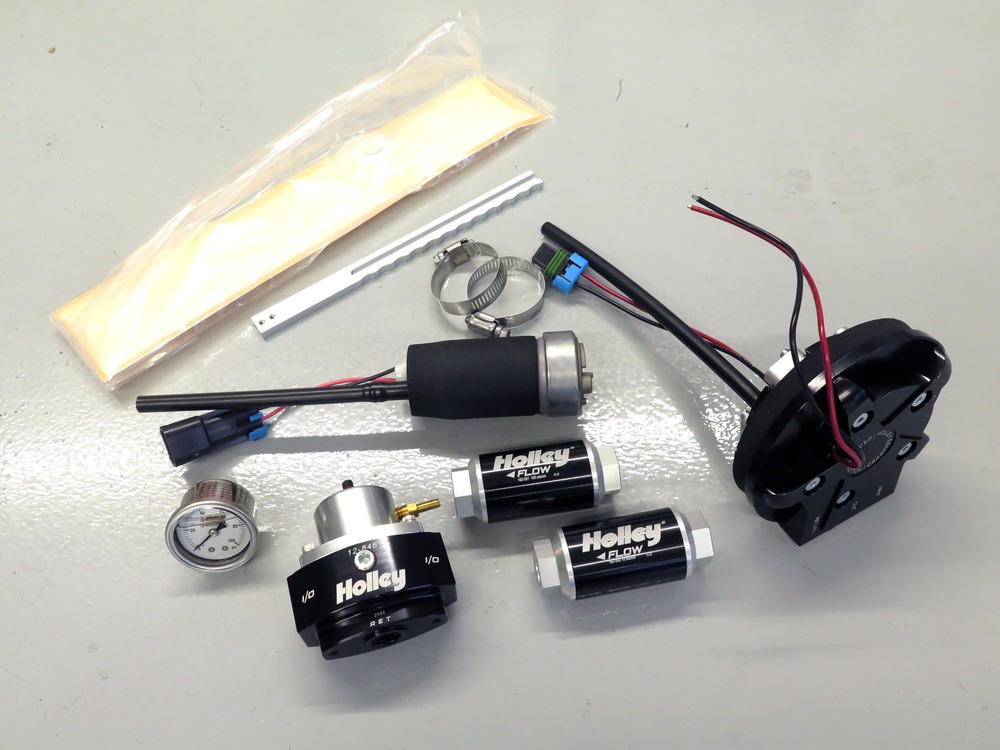

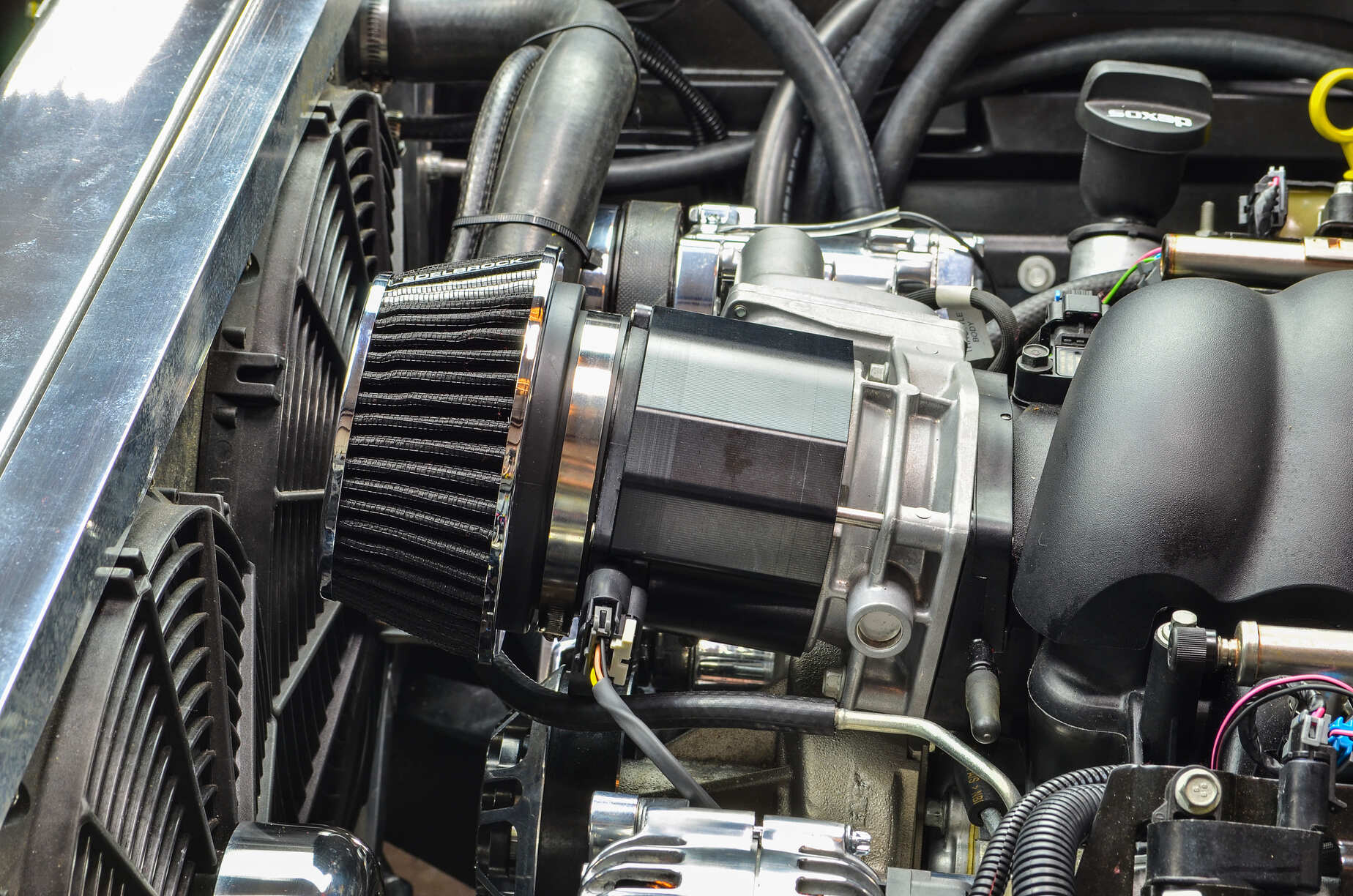

On the face of it, an LS swap seems like a slam dunk to gain reliable power in a compact package, but there are a few things to consider. For one, the addition of sensitive electrical components, such as the ECU, requires a charging system that is in peak performance. A charging state below 12 V will yield in unhappy electrical components, resulting in some unsavory situations. EFI fueling needs are also different than that of the traditional, mechanically fed, carbureted system. Coolant hose locations can also vary enough to warrant a radiator upgrade, especially when swapping from a six-cylinder application. Speaking of cooling, the typical LS engine swap will require the addition of an electric fan, which means sourcing said fan, shroud, and mounting source, as well as the necessary electrical support (additional wires, relay). Mounting that LS engine can be as simple as purchasing a pair of adapters to mate the new engine to existing V-8 mounts and moving, modifying, or purchasing a transmission mount.

Check it out: Automotive Specialists Updates the Classic 409 for a New Millennium

Likewise, getting that LS engine in place could be as complex as fabricating new mounts from scratch. Many LS engines utilize a relatively deep pan that can foul the front crossmember of many classic Chevys, requiring a new, LS-swap oil pan. The difference between the new LS exhaust collector and the old also means modifications to the exhaust will be needed, if not a completely new system. Driveshaft lengths will also vary, depending upon the original equipment, likely required an upgrade there as well. And while we’re speaking of upgrades, that old rearend might need to be addressed if a significant increase in power is expected.

Here at Clampdown Competition, we’re gearing up to perform an LS swap on a ’57 Chevy Handyman using an LS3 Connect & Cruise from Chevrolet Performance Parts, so while all of these requirements are fresh in mind, we thought we’d take a look at some of the things to consider when contemplating such an undertaking. Like they say, knowledge is power and when it comes to performing an engine swap as drastic as an LS changeout, there are a lot of things that need to be known before making such a commitment.

ACP

Sources

Chevrolet Performance Parts

chevrolet.com/performance-parts

Clampdown Competition

clampdowncomp.com

Classic Performance Products (CPP)

(800) 522-8309

classicperform.com

Concept One Pulley Systems

(866) 532-6594

c1pulleys.com

DeWitts Aluminum Radiators

(517) 548-0600

dewitts.com

Holley Performance Products

(866) 464-6553

holley.com

Speedway Motors

(855) 313-9173

speedwaymotors.com/allchevyperformance