Making the Jump to a Modern Valvetrain in your Big- or Small-Block Chevy

By Evan Perkins – Photography by the Author

It wasn’t long ago that a trick roller camshaft in a small-block Chevy was high-end, drag race tech that looked good in glossy magazine pages but was yet out of reach for the average hot rodder. Boy, how times have changed. These previously exotic grinds have trickled from “can’t get it” to “can’t afford it,” all the way down to “Yeah, my Silverado came with that.” And whether we’re talking classic big- or small-block or late-model LS/LT, roller camshafts are here to stay. Today, they’re a practical, readily-available upgrade to any big- or small-block engine.

Defining a Roller Cam

One of the misnomers that has long plagued the hot rod world is the word roller. While always referring to wheels riding on steel roller bearings (as opposed to bushings or babbitt bearings) the word roller is often applied, misleadingly, to other valvetrain components. You see, the rocker arms that are actuated by the camshaft, lifter, and pushrod can also incorporate roller bearings that reduce friction and increase longevity, but adding a roller rocker arm setup, while important, isn’t near the performance boost as a roller cam. Terms like “roller motor” and “full roller” are tossed around often in bench-racing circles and online ads, but there’s no beating a genuine roller cam.

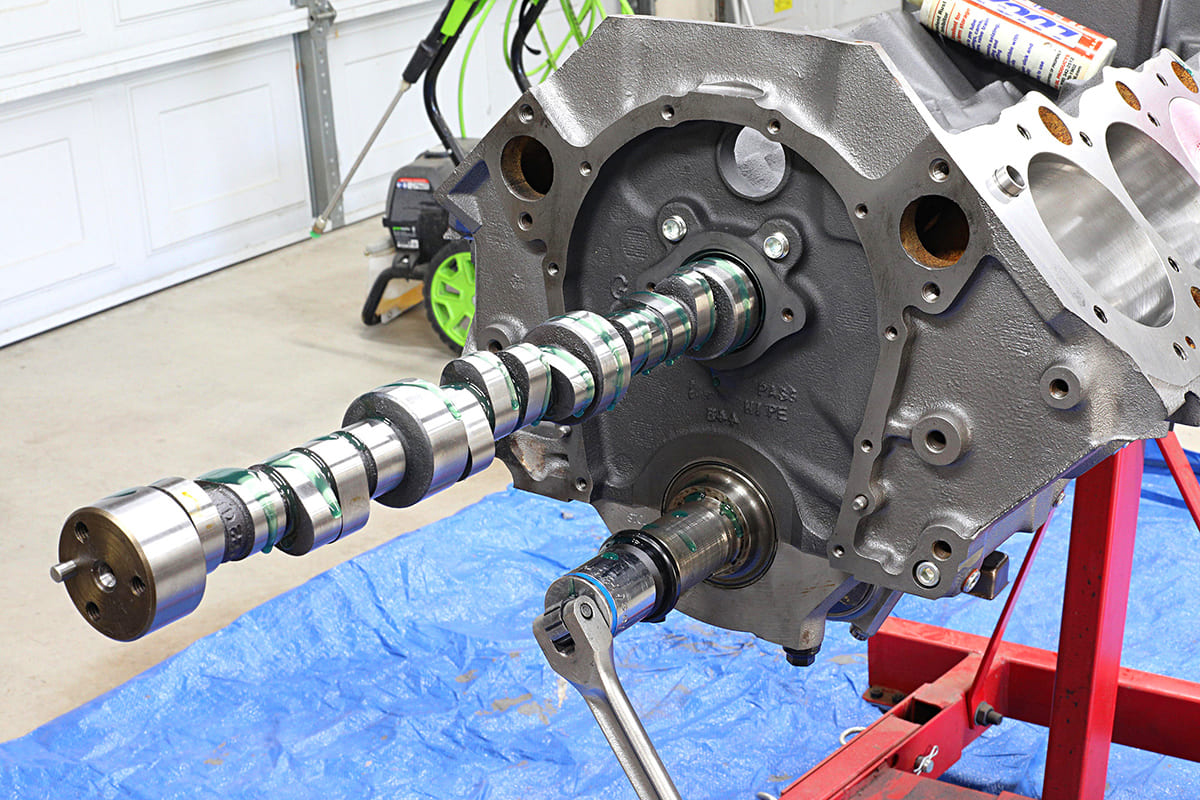

When applied to camshafts, the word roller corresponds to the interface between the cam lobe and lifter. In older engine architectures, the lifter was of a flat tappet style (see last month’s issue), where the crown of the lifter rode directly on the cam lobe with no roller bearing assistance. The lifter had a slight taper to it and touched the lobe only on its outermost edge, which caused the lifter to spin in its bore during engine operation.

This style of camshaft has worked well since the dawn of the internal combustion engine and continues to be widely available for engine builders today. However, when Chevrolet introduced their factory, roller cam–equipped engines in 1987, performance soared to a new level.

While a reduction in friction is always a good thing in an internal engine, the key benefit of its roller cam is its ability to accelerate the lifter up its lobe face much, much quicker than a comparable flat tappet cam. This means that the valve will get to a higher lift where it can flow more air sooner and stay there longer. This is called “area under the curve” and it’s hugely responsible for why a roller cam with a similar duration and lift specs to a flat tappet cam will make more horsepower and torque.

“Hydraulic rollers open the customer up to higher lift and more area under the curve, which is especially good with heads that flow great at higher lift,” Comp Cams valvetrain engineering manager, Billy Godbold, says. “If the customer puts together a good package, especially in terms of a well-matched camshaft and valvesprings, there will be a significant power improvement.”

An added benefit to roller camshafts is that the reduced friction of the roller wheel and the lack of metal-to-metal wear of a flat tappet camshaft contributes to a much longer service life. This style of camshaft is also less dependent on oil type and is much easier and quicker to break in on a fresh build.

Making the Jump to a Roller Camshaft

If you’ve decided your old small- or big-block needs a shot in the arm for some added grunt, or you have a fresh build in the works and are to pull the trigger on a valvetrain setup, here are some things to consider:

Valvesprings

Flat tappet cams require a much softer valvespring package than a roller. When moving to a roller camshaft it is important to match your camshaft and spring. Failure to do so will cause a loss of valve control, commonly referred to valve float, which can occur at surprisingly low rpm. When valve float occurs every part of the valvetrain, from the cam lobe to the valve face, gets absolutely hammered and it’s a surefire way to hurt something, quick!

“Valvesprings always need to be selected around the target lift,” Godbold says. “You never want to run a 0.700-inch lift spring with a 0.600-inch lift cam or a 0.600-inch spring with a 0.500-inch camshaft. Leaving too much room to coil bind is the number two mistake we see with spring installation. The number one is leaving too little, as that causes an even bigger mess. Generally, about 0.060 to 0.120 inch is a good target, but some special applications might like to be a bit out of that window.”

Camshaft Thrust Control

Flat tappet camshafts have their lobes ground with a slight tilt that spins the lifters as well as naturally caused the cam to want to push itself toward the back of the engine. Because roller cam lobes are completely flat, this phenomenon does not occur and the camshaft will actually try and lurch forward, away from the distributor gear, under load and increased engine speed. This causes the ignition timing–remember, the distributor is driven by the gear on the back of the camshaft–to become inconsistent. If too much movement occurs, the lifter wheel can actually ride off the lobe and carnage will ensue.

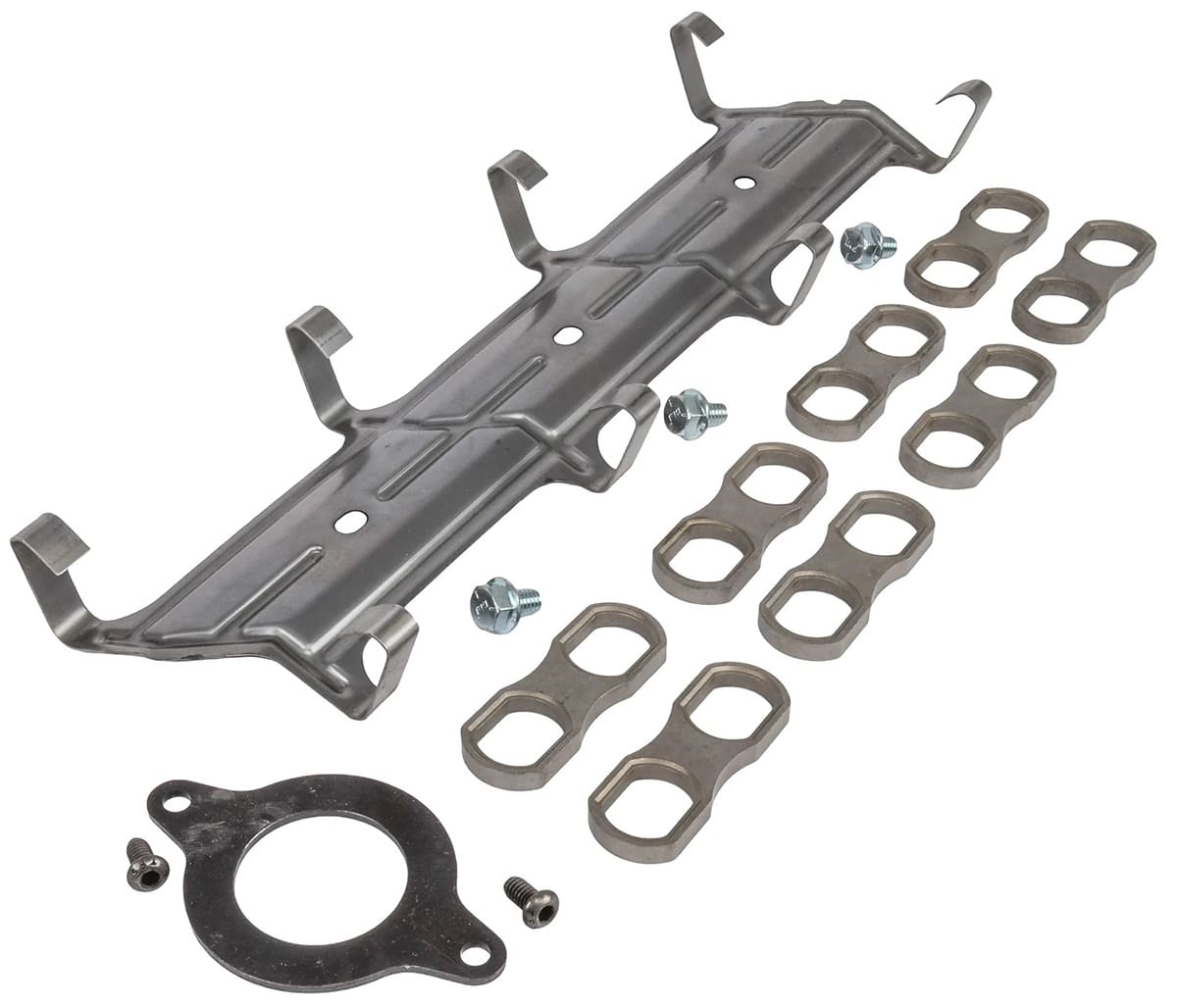

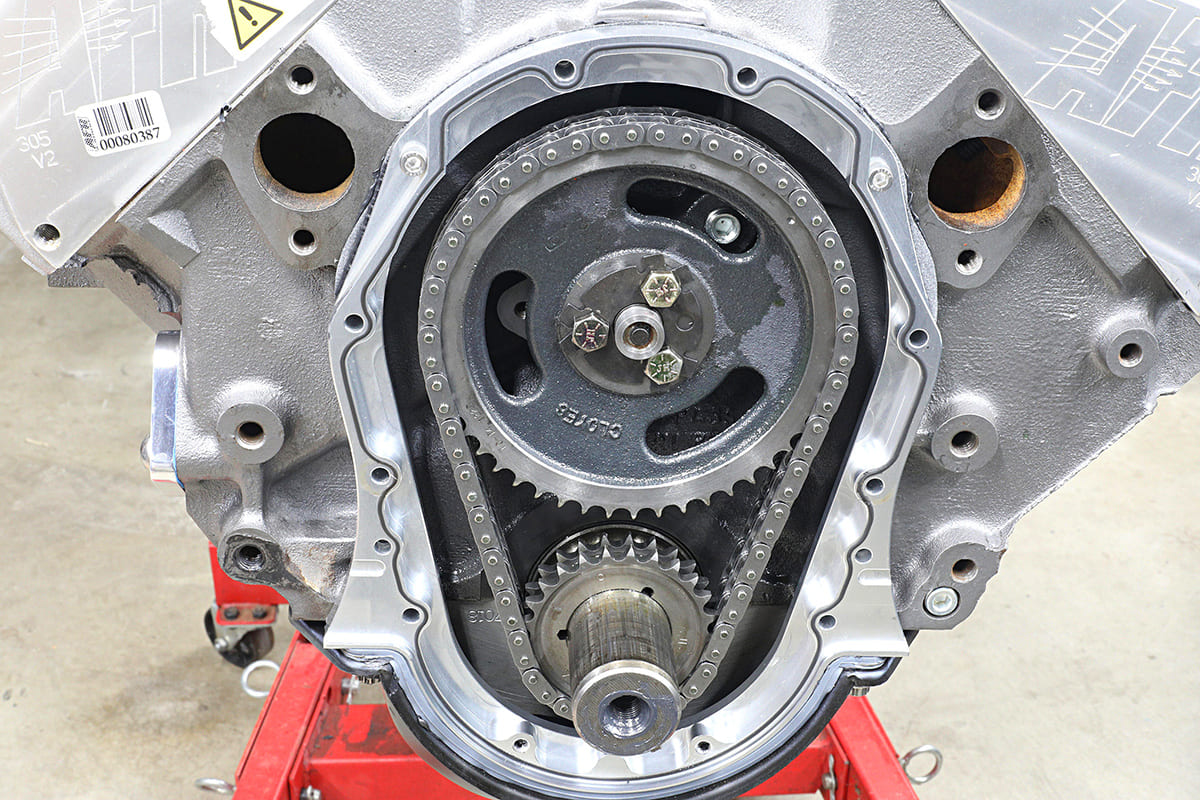

To prevent the camshaft from thrusting forward, there are a few different options, depending on what year of block you have. On older engines, a thrust button, which mounts in the center of the camshaft timing gear, is used to allow only limited camshaft movement before riding against the inside of the timing cover. These buttons are very simple to install and are available in solid styles, such as nylon, or with small Torrington bearings (roller buttons).

“You definitely have to decide on thrust control on an small- or big-block Chevy,” Godbold says. “Generally, a button works great, but there are no bad ways to do this, except maybe a using good roller button and a cheap timing cover.”

If you have a late-model big- or small-block Chevy that was originally fitted with a factory roller cam, you have the option of using a camshaft retainer plate (cam stopper) that rides on a machined step on the nose of the front camshaft bearing journal. Not all cams have this step so if ordering a new one, you’ll need to verify with the manufacturer what year your block is. If the cam does not have this stepped provision, a cam button can easily be substituted.

Distributor Gear Material

Roller camshafts, just like their flat tappet counterparts are available with hydraulic or solid lifters. In certain cases, choosing a cam intended for solid roller lifters will require it to be made out of a more robust steel material. In this situation, certain cam core alloys can be incompatible with a standard vast iron distributor gear. In these cases, a brass or composite distributor gear can be used. Though Godbold points out, this problem isn’t the issue it once was.

“With the wide availability of melonized (nitrided) distributor gears on the market today, the cam gear problem has basically gone away,” Godbold says. “You can run a melonized gear on any camshaft material.”

It’s always a good idea to check your cam card, which should clearly state if a specialty gear is required.

Pushrod Length

The often-forgotten pushrod plays a simple yet vital role in the valvetrain and swapping from a flat tappet cam to a roller cam will affect it all the same. This juncture not only represents a great time to toss any flimsy, stock pushrod and step up to a high-quality alloy, thicker-wall, or larger-diameter performance unit, but you’ll also inevitably need to reevaluate pushrod length. Hydraulic roller lifters, in order to accommodate the extra height of the roller wheel, are often significantly taller than a flat tappet lifter and this change will require a shorter pushrod to accommodate the added height.

With a couple considerations, some attention to detail, and some general understanding, swapping a roller camshaft into your next engine build is worth power, torque, and a newfound appreciation for what your engine can do!

Sidebar: Did You Know?

While there is much technology that trickles backward from the racing world and late-model OEMs, occasionally something just plain works and everyone opts to leave well enough alone. As an example of this, OEM roller-equipped small-block Chevy engines, big-block engines, and LS engines use the same hydraulic lifter from the factory.

Sources

Comp Cams

(800) 999-0853

compcams.com