Bobby Alloway Lets Us Take a Peek at What’s Coming

By Gerry Burger – Photography by Toby Caldwell

For some reason I am always interested in that first car. Bobby Alloway’s first car was a 1956 Ford “post car.” It was quickly replaced with a 1965 Plymouth Sport Fury with a 426 wedge underhood, followed by a 1970 AAR ’Cuda . He enjoyed these muscle cars and still has a great appreciation for the muscle car era, but in the early ’80s he was drawn back to the classic Ford hot rods, particularly the Model 40, 1933 and 1934 Fords. After some changes at his “day job” he decided to open a hot rod shop in Louisville, Tennessee; this was in 1992. And the rest, as they say, is history—but history doesn’t happen overnight.

(photos 35)

Over the past 40 years or so there have been several milestone cars/hot rods that put Alloway “on the map.” There was the super-slick 1933 Vicky that won the Ridler in 1985, and then 10 years later when Alloway’s own flamed three-window coupe and Tom Clark’s matching flamed roadster visually and figuratively set the street rod world aflame. First impressions are often indelible. The image of those two black flamed hot rods roaming the country together forever cemented the Alloway image for me and many others. Say Bobby Alloway and black with flames comes to mind. That vision would be short-selling Alloway and the entire crew at Alloway’s Hot Rod shop, as they build diverse makes, models, and years of hot rods. Like most shops, cars of the ’50s and ’60s are now fair game, and cars such as Kathy Lange’s Street Rod of the Year–winning 1958 Edsel prove the point. Currently, there are three Chevy El Caminos under construction in the shop (one 1959 and a pair of ’70s) along with a C2 Corvette, and while the body styles may range from a Deuce roadster to a 1958 Impala, they all have some common traits. First and foremost is quality; every car to leave the shop is built to an incredibly high standard. Second is functionality. Alloway-built cars can take to the open road. Third is the whole wheel/tire combination and that wicked stance that defines the “Alloway look.” Just the fact that the “Alloway look” exists is a testimony to the man and his shop.

So how does one achieve that iconic look? Well, it would be nice if there was a formula or more modern terms, like “there’s an app for that,” but unfortunately neither exist. As for the stance, it is a bit of a conspiracy. It often begins with the car and a set of wheels sighted from 55 away. The suspension has been removed from the stock chassis and the car is rolled outside with dollies under the stock frame. The wheels are then tucked up under the body and floorjacks raise and lower the front and rear of the car while Alloway gives it the eyeball from about 50 feet away. Once again, no need for calculators, lasers, or levels, just one man working the jack while Alloway provides directions, “come up a little in back, no not that much, down a little,” then to the front, “drop it down a bit, go a little more.” The process continues until the final order comes, “that’s it, right there.” Having witnessed this process for the abovementioned Edsel, it is a very simple process that requires one important tool: a great eye.

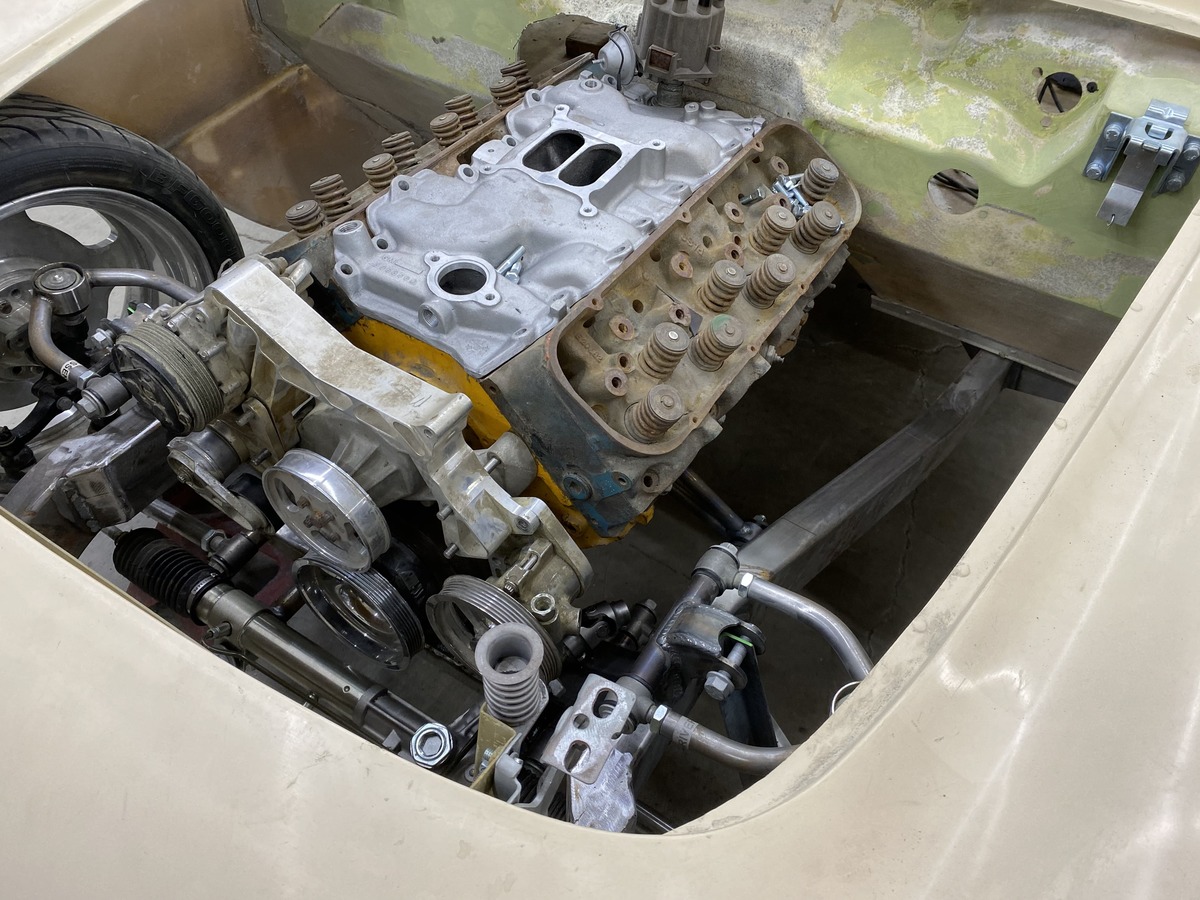

With the wheel/tire combo and stance set it is finally time to take critical measurements, and this is where the conspiracy comes into play. These critical measurements are generally sent off to co-conspirator Art Morrison for a completely new chassis, including engine and tranny measurements.

Speaking of engines, part of the Alloway image was built around the big-block Chevy motor. It was the engine of choice for many of his cars. Today you can find engines ranging from a Coyote in an Edsel, a Cammer motor in a 1961 Ford, and so diversity continues underhood.

As for body modifications there is a heavy dose of respect built into all Alloway cars. Respect for the original design. Recognizing the beauty in the original car is key to making subtle modifications that actually improve the look, always conscious that the goal is to improve the look rather than change the look. For that reason, there are no changes made simply for the sake of change, and often when asked why a certain body modification was performed the answer is this simple: “I thought it would look better that way.” Top chops and other modifications are done much like the stance, tweaking things until you find the sweet spot. Often the best modifications are the ones most difficult to see, like a recontoured fender opening or a slight rake on the grille.

(photos 36)

As for Bobby Alloway the man, much has been written about him and we are here to tour his shop not write a biography. He’s a low-key guy with a warm, friendly approach to life. Soft spoken, he is not one to brag about things like winning two AMBR trophies, the Ridler, or any number of awards. Like most people who are truly good at something, he prefers to let his work do the talking. While Alloway still works on the cars in the shop, he is quick to credit his talented team at Alloway’s Rod Shop for their fine work. The crew includes Joe Bailey, Josh Bailey, Jeff Plemons, Jordan Boone, Toby Caldwell, and Glenn Shabbas. Together this prolific shop turns out about six cars a year, not counting the annual Shades of the Past giveaway car. Every car is different, and we can guarantee every car is special. MR