Antiroll Bar Tech: Where Bigger Isn’t Always Better

By Jeff Smith – Photography by the Author

Everybody wants a car that handles well. Any new car built in the last 30 years will far out-corner a stock ’60s machine with little trouble but it is also easy to upgrade and improve corner prowess with the bolt-on simplicity of an antiroll or sway bar. But once you dive into the nuances of suspension modifications, the answer isn’t always just to bolt on the biggest bar. It’s a bit more complicated than that. So let’s dive in.

Factory cars from the ’60s were especially weak in suspension design with regard to improved handling. This is evidenced by soft spring rates, very tiny antiroll bars, and less-than-ideal alignment specs, which were all aimed at driver comfort rather than any attempt at better handling. But that means there are plenty of opportunities for a simple and effective upgrade with the addition of a front and/or rear antiroll bar. The approach for this story will be aimed at the average street enthusiast who just wants a slightly better handling machine.

We’ll focus our initial discussion on front antiroll bars and slide into rear bars. The idea behind an antiroll bar is to increase resistance to roll when the car is driven into a tight corner at an aggressive speed. The front suspension’s normal reaction in a lefthand turn is to compress the right front spring. Of course, you could minimize this roll with very high-rate springs, but that also affects ride quality, so another way to minimize body roll is with a torsion bar that connects to the frame and also to both lower control arms. As weight transfer attempts to pitch the body, the bar’s diameter and lever arm combination work to resist this body roll.

Check it out: Third-Gen Camaro Rear Suspension and Brakes and Rearend Upgrade

It should also be emphasized that suspension tuning is very much a team sport, meaning that all the players at both ends of the front and rear suspension have an important part to play in this handling game. This means that while a stiffer antiroll bar will certainly improve the handling game, other components like spring rates, shock absorbers, control arms, chassis stiffeners, and other components are also essential components. And if you’re like us, that first improvement always seems to lead to diving further into the program in the search of even greater performance!

An antiroll bar is nothing more than a torsion bar configured to easily mount to the vehicle. A torsion bar operates by creating resistance to motion based on load input on one end against a fixed position on the opposite end. The bar’s diameter and length combine to create a resistance to being twisted. Length plays a part since a shorter bar of the same diameter offers a higher rate than a longer version. The rate is generally expressed in pounds of resistance per inch of travel. Most factory replacement antiroll bars are bent to establish a fixed lever arm on each end. The bar’s rate is directly affected by the length of the lever arm. It should make sense that a given diameter bar using a longer lever arm will deliver a lower rate compared to the same diameter bar with a shorter lever arm.

This becomes less of an issue with bolt-on antiroll bars because in most cases the lever arm length is fixed for the application, so the main variable is the bar’s diameter. The quickest way to evaluate a typical antiroll bar for a specific vehicle is to measure its cross-sectional diameter. A larger-diameter bar will always be stiffer than a smaller diameter for the same vehicle. Since the lever arm distance will remain the same for any given vehicle like an early Camaro, Chevelle, or ’55-57 Chevy, the main variable that remains is the bar diameter as a way to change the resistance value.

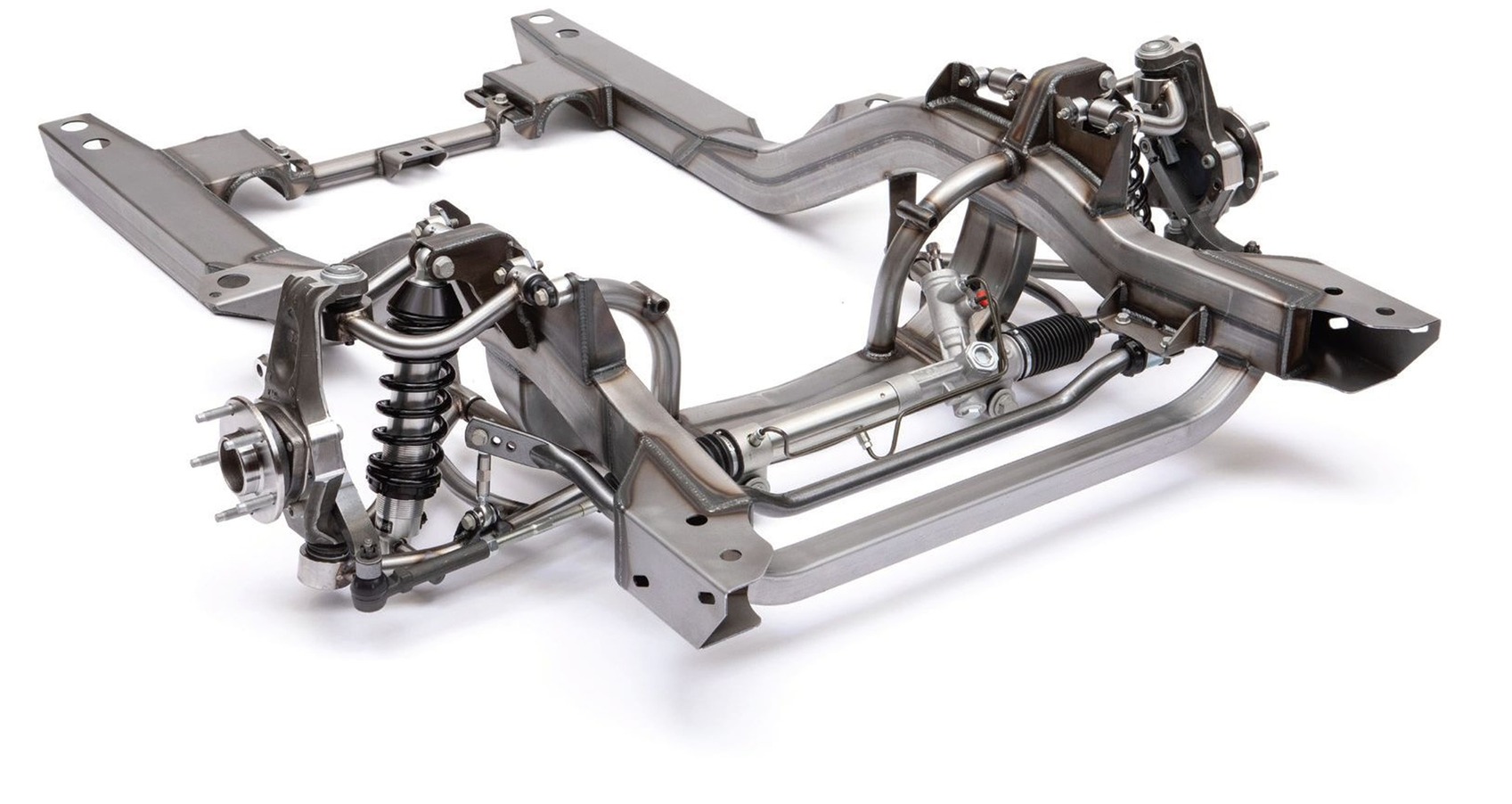

A slightly different approach to the front antiroll bar that is becoming increasingly popular are the splined sway bar kits. These bars employ a straight torsion bar located inside an outer housing. Both ends of the torsion bar are splined to lengths of steel or aluminum arms that attach (in the case of a front antiroll bar) to the front lower control arm. A similar arrangement can also be applied to the rear suspension. The advantage of the splined bar is that if at a later point a slightly stiffer or softer bar is required, it’s easy and sometimes less expensive to make the change. Or the lever arm can also be changed separately. Plus, for more advanced suspension tuners, these straight bars can be varied in wall thickness to effect minor changes in rate.

More Suspension: Rebuilding a Chevelle’s Front Suspension with CPP

As an example, we looked at Speedway Engineering’s chart on typical hollow splined torsion bars 37½ inches in length. If the length of the lever arm is increased by 50 percent (from 6 to 9 inches, for example), this decreases the effective rate of the bar by 33 percent. We can also decrease the rate of our torsion bar by 33 percent by changing from a 1-inch to a 7/8-inch diameter. These percentages will change with both length and bar diameter, but this at least offers an idea of how these bars can be tuned to produce the rate required.

In an accompanying chart, we’ve also listed a test performed by Hotchkis on the effect of changing from a solid to a hollow bar. The bar diameters in this test are not the same, but because there is relatively little torsional resistance offered near the center of a solid bar, a hollow bar with a given wall thickness can be stiffer than a solid bar. In the Hotchkis test, the hollow bar is 1/8-inch larger yet still delivers a 19 percent increase in stiffness despite being 9 pounds lighter.

Some people consider a front sway bar to be sprung weight because it is bolted to the frame. But since a portion of the bar is also attached to the lower control arm, a portion of the bar is assigned as unsprung weight. In all applications the ideal situation is to minimize the unsprung weight. In the case of a rear antiroll bar attached to the lower trailing arms on a Chevelle rear suspension the entire bar would then be considered unsprung weight.

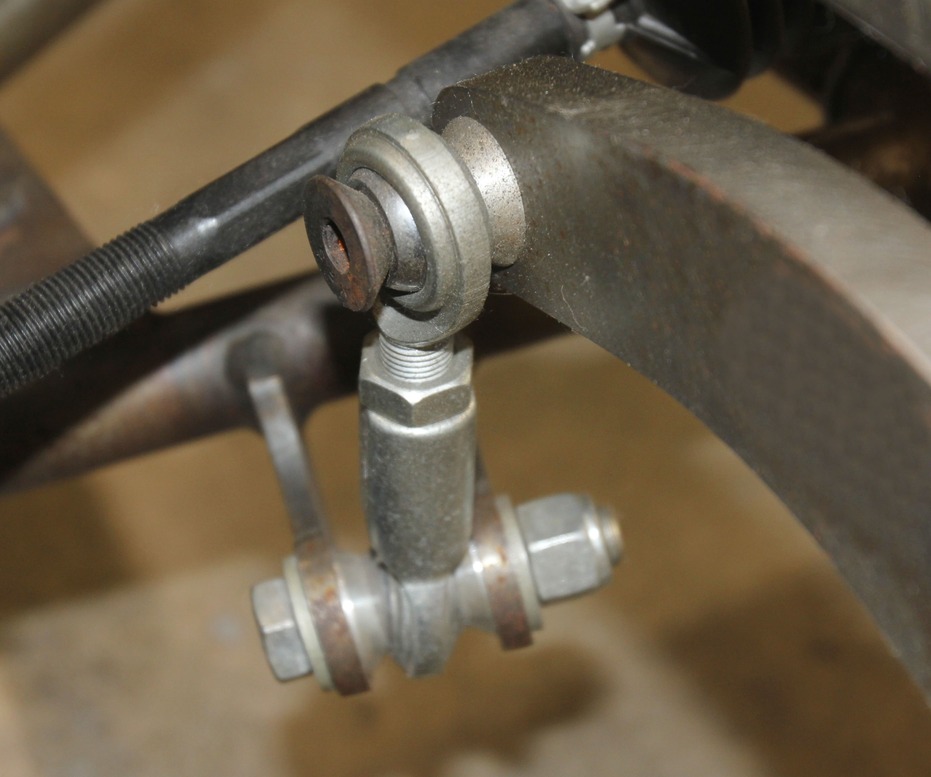

Now that we’re on the topic of rear antiroll bars, it’s worth looking at rear antiroll bar mounting positions of various designs. GM often attached its antiroll bars directly to the lower control arms. While this is a convenient place to attach the bar, this location also reduces the bar’s effectiveness. This occurs because the functional lever arm length is not just the length of the attachment portion of the bar. Instead, the true lever length actually begins where the trailing arm is attached to the chassis. This drastically increases the length of the lever, which then reduces the resistance offered by the bar diameter. A more effective placement is to attach the lever arm directly to the frame of the car instead of to the lower control arms. Some aftermarket rear bars are constructed this way. While they require more installation effort, the return is certainly worth the time spent.

Armed now with this baseline of torsional twist tech, there are a number of factors that go into selecting the right antiroll bar. We have some experience with early Chevelles and much of this also applies to other Chevy muscle cars. A larger antiroll bar is a great first step in reducing body roll while not drastically hurting ride quality. Someone way back in the ’80s discovered that second-generation ’70-81 Camaro and Firebird antiroll bars were a direct retrofit to an early Chevelle, so adding a 1 1/8-inch Trans Am bar was a great step up from those wimpy stock 7/8-inch bars. Even with a larger front bar early Chevelles still tend to understeer, so adding a rear bar tends to stiffen the rear suspension and this helps reduce the tendency toward understeer.

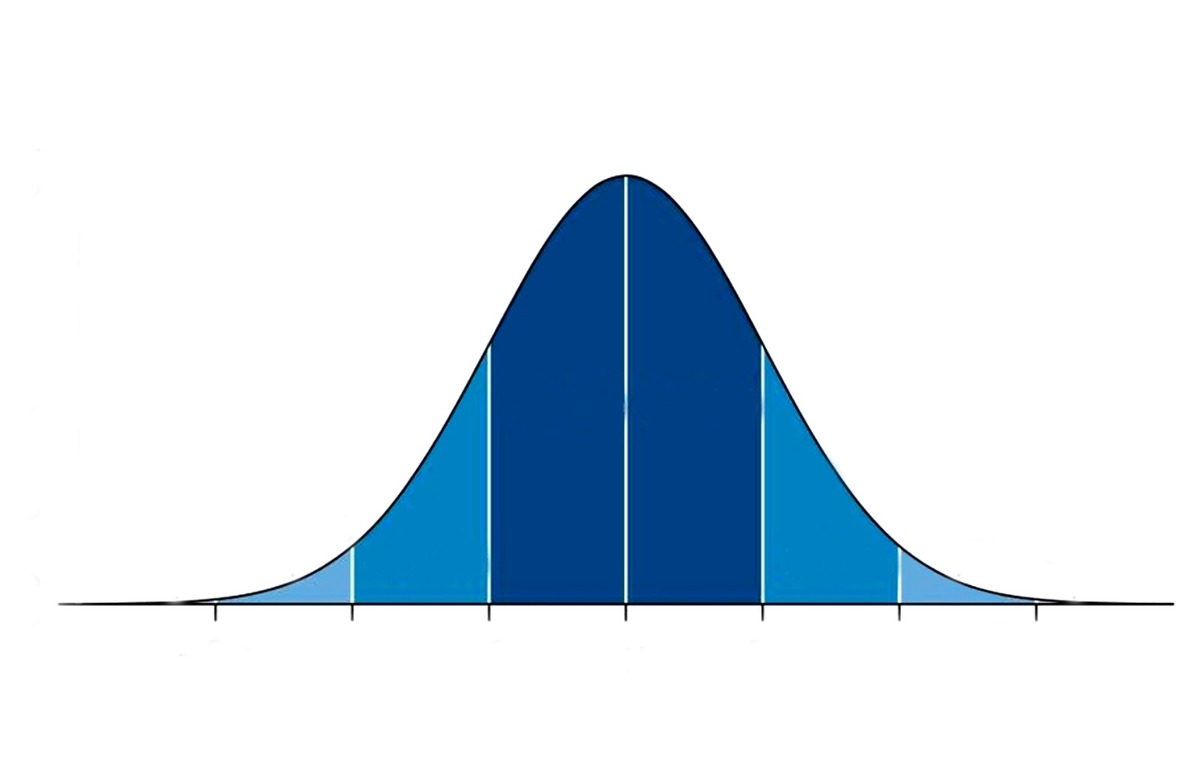

However, other front suspension components to improve corner entry eventually get to the point where the rear is now too stiff and the car will want to oversteer. That’s when the rear bar should be removed to soften the rear suspension and allow the car to remain neutral on corner entry. But if we continue to stiffen the front suspension in our quest for higher corner entry speeds, the car will eventually begin to understeer because it’s too stiff. We’ve included a graph of a classic bell curve that might help explain this series of events, if you think of the horizontal axis of the graph from left to right representing increasing stiffness in the front suspension. A car can understeer as a result of too little front roll resistance or it can also understeer from excessive roll resistance. This is a very simplistic evaluation because the back half of the car also affects this situation, but at least this offers some clues to suspension dynamics.

So far we’ve only discussed antiroll bars for turning corners but they can also be used in drag racing. Street cars tend to have somewhat compliant chassis, especially if not improved with reinforcements or a rollcage. We’ve all seen cars leave the starting line with the rear tires firmly planted while the front half of the car is twisted like a pretzel. This occurs with a combination of excellent traction and sufficient torque to literally twist the car. Rear antiroll bars are designed to reduce this twist by employing a large rear bar bolted to the rear axle and to the frame of the car to limit this body movement.

This story has really just touched on the high points of this subject matter without getting into more exotic ideas, such as the blade type antiroll bars that are rate adjustable by making a small change in the angle of a blade-style connector. These types of bars have yet to make their name in the domestic street/autocross/road course market but are already found in race cars and upscale import vehicles. Expect to see more of these as the corner-turning set bumps up the technology curve; all in the name of negotiating corners a little bit quicker.

This is a partial list of replacement antiroll bar diameters for ’64-67 Chevelles and ’70-81 Camaros. A stock front bar for an early Chevelle was generally 7/8 inch in diameter so a 1 3/8-inch bar is a radical increase in torsional stiffness.

| Company | Bar Dia. (inches) | PN |

| Addco | 1 1/8 | 883 |

| Addco | 1 ¼ | 709 |

| Addco | 1 3/8 | 2278 Tubular |

| CPP | 1 1/8 | CPP883 |

| CPP | 1¼ | CPP709 |

| Heidts | 1 1/8 | SB071 |

| Global West | 1 1/8 | SB-883 |

| Global West | 1¼ | DB-884 |

| Hotchkis | 1 3/8 | 2202F |

| QA1 | 1¼ | 52870 |

| Ridetech | 1 3/8 | 11239120 |

Hotchkis’ test of solid versus a tubular (hollow) sway bar. Note how the tubular bar, while larger yet 6 pounds lighter, also delivers a 19 percent increase in roll resistance rate.

| Solid 1 ¼” Bar | Tubular 1 3/8” | Tubular Difference | |

| Weight | 22.5 lb | 16.4 lb | 6.1 lb lighter |

| Rate | 477 lb/in | 567 lb/in | 90 lb/in stiffer |

Sources

ADDCO

(800) 338-7015

addco.net

Art Morrison Enterprises

(253) 922-7188

artmorrison.com

Classic Performance Products

(866) 517-0430

classicperform.com

Global West Suspension

(909) 890-0759

globalwest.net

Heidts

(800) 841-8188

heidts.com

Hotchkis Performance

(877) 466-7655

hotchkisperformance.com

Performance Online

(888) 991-1697

performanceonline.com

QA1

(952) 985-5675

qa1.net

Ridetech

(812) 482-2932

ridetech.com

Roadster Shop

(847) 949-7637

roadstershop.com

Scott’s Hotrods ’N Customs

(800) 273-5195

scottshotrods.com

Speedway Engineering

(818) 362-5865

1speedway.com

Speedway Motors

(402) 474-4411

speedwaymotors.com