A Tribute Build of the Legendary All-Aluminum Big-Block Delivers Big Torque and Greater Street Performance

By Barry Kluczyk – Photography by the Author

It’s been said that legends rarely live up to their hype, but the original, all-aluminum ZL1 big-block did just that.

Originally conceived as a lightweight racing engine for the Can-Am road racing series (Group 7), the original, solid-lifter 427ci ZL1 engine was never intended for production vehicles, but Chevrolet’s motorsports engineers never counted on an enterprising and forward-thinking Illinois dealer named Fred Gibb. He used Chevrolet’s COPO (Central Office Production Order) special-order system to produce the legendary Camaro ZL1.

Even though the engine made its mark earlier and continued to be used in racing into the ’70s, it was in those 69 ’69 Camaros—and a pair of Corvettes—that grew the myth of the ZL1. Over the years, Chevrolet stoked the embers, including a reissue of the aluminum cylinder block, which spawned a Ram Jet-topped ZL1 crate engine and an anniversary 427 crate engine.

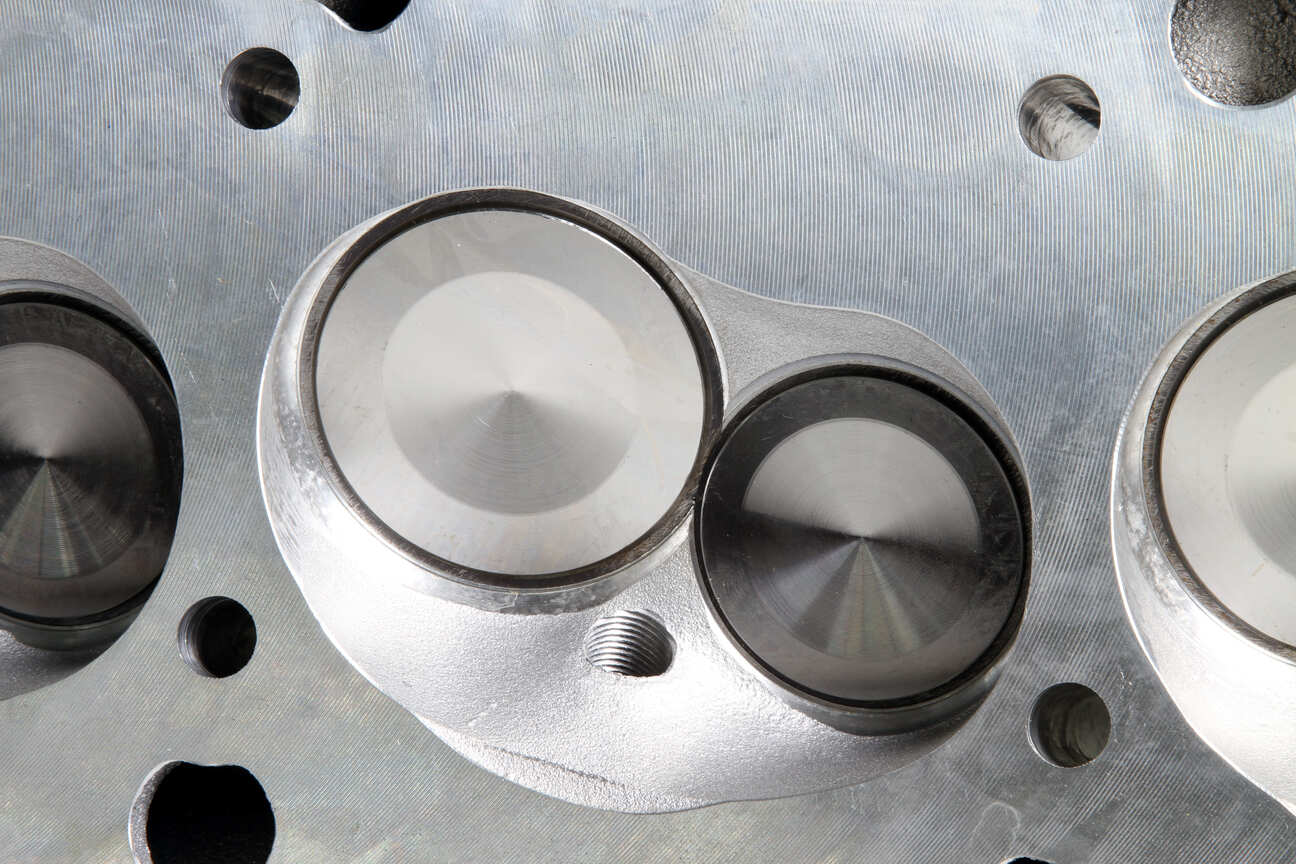

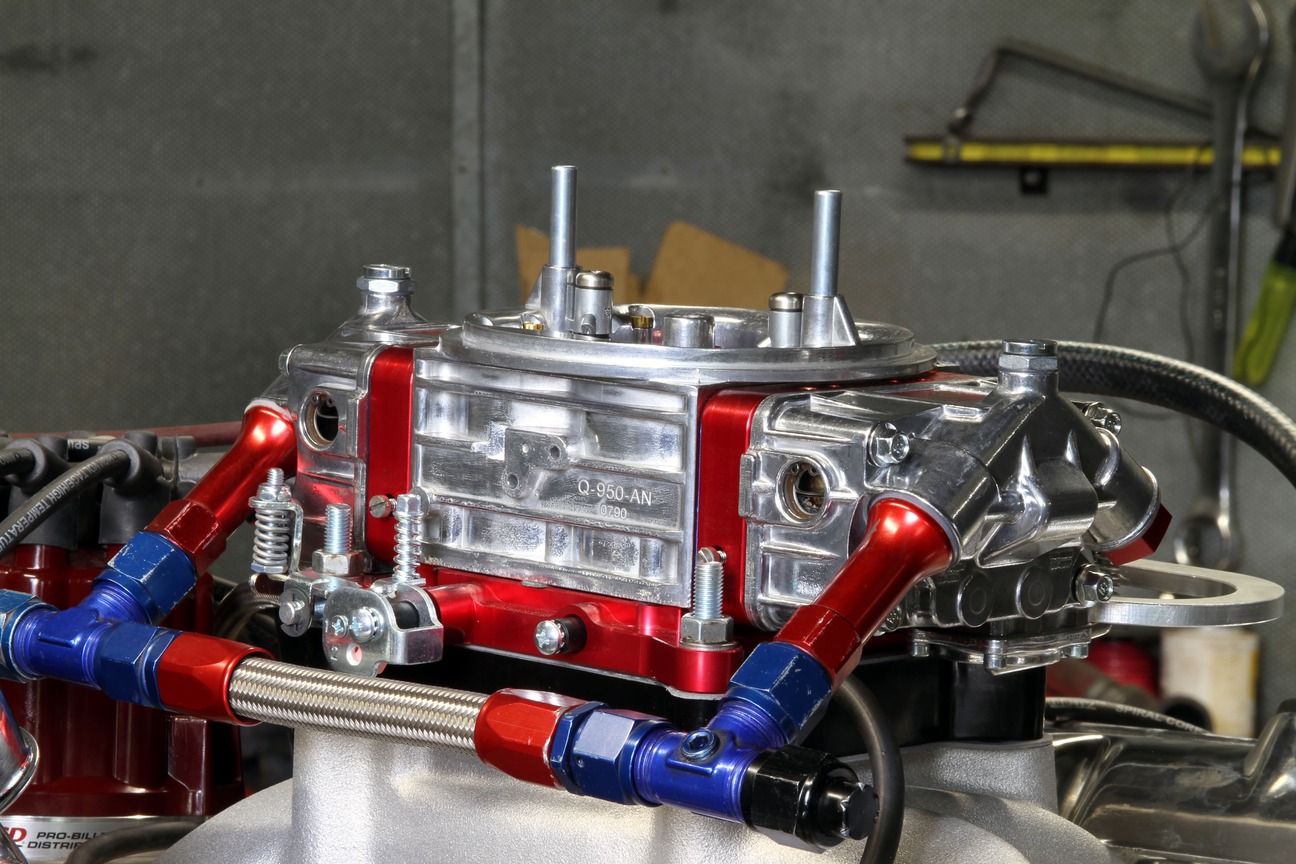

In the production cars, the engine was officially rated at 430 hp, but true output was closer to 525-530 horses, which was no small feat for a naturally aspirated engine in its day. The basic recipe included a 12:1 compression ratio, a mechanical cam with 0.560/0.600-inch lift, and open-chamber heads based on the L-88, but with slightly larger exhaust ports. It was all topped with an 850-cfm Holley double-pumper. Serious stuff back then.

More Chevy Engine Goodness: Top 10 LS Engines

More than 50 years later, it’s a performance threshold that’s still admirably lofty. Consider the 6.2L LT2 in the C8 Corvette. It’s 12 percent smaller in displacement than the ZL1, but with a comparable compression ratio of 11.5:1, and it’s rated at 490 hp. Assuming the ZL1’s true output was closer to 530 hp, but we shave off 12 percent to equalize the displacement with the LT2, the rating comes down to 467. Considering the LT2 employs advanced technologies, such as cam phasing and direct injection, it’s an awfully close comparison to the capabilities of a single-carburetor-fed big-block from more than half a century ago.

It’s worth noting that the LT2 breathes through exhaust headers that look like they were scavenged from an offshore racing boat, while the ZL1 wheezed through restrictive cast-iron manifolds. A set of headers on the old ZL1 would have easily closed the 23hp gap between the engines.

In other words, it really was true that there was no replacement for displacement. And a big, solid-lifter cam. And high compression.

A Modern Tribute

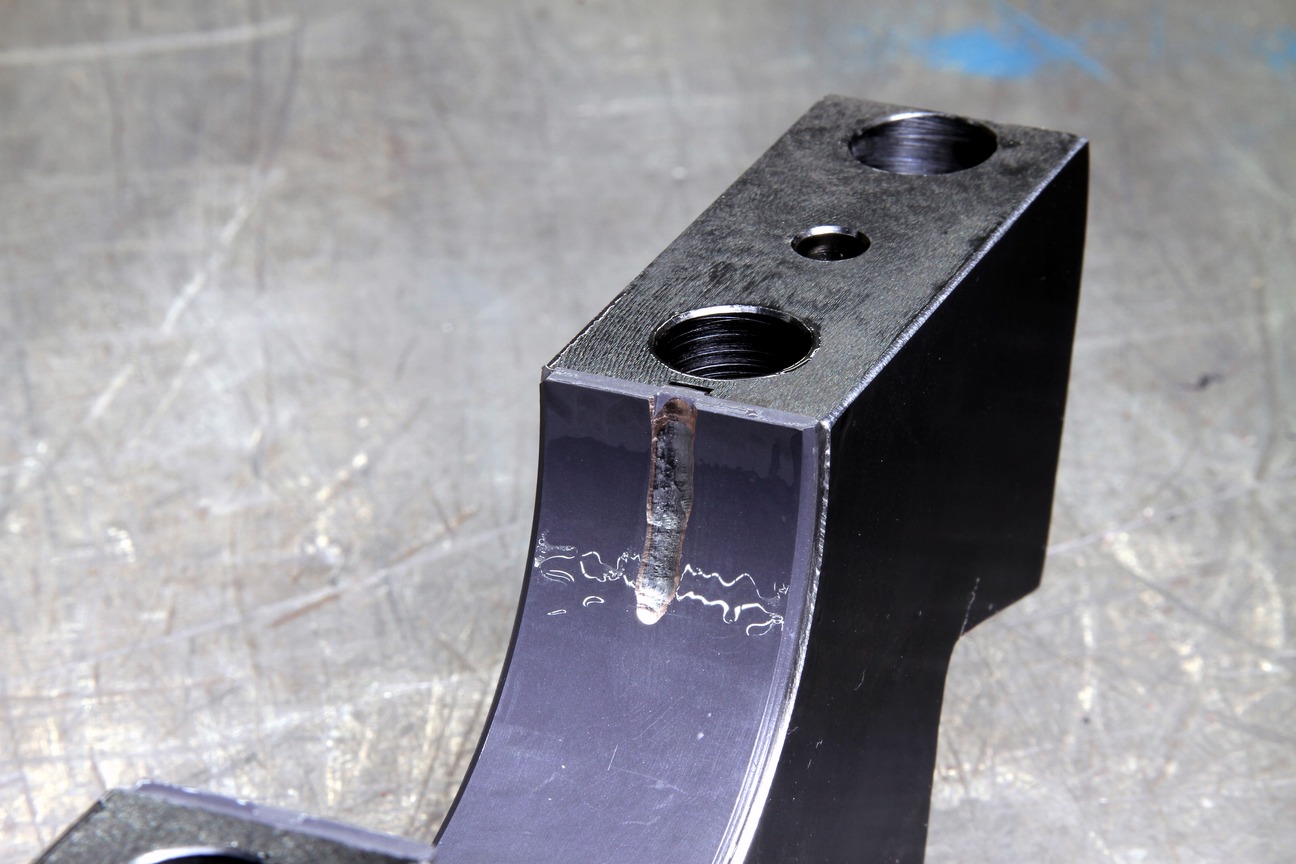

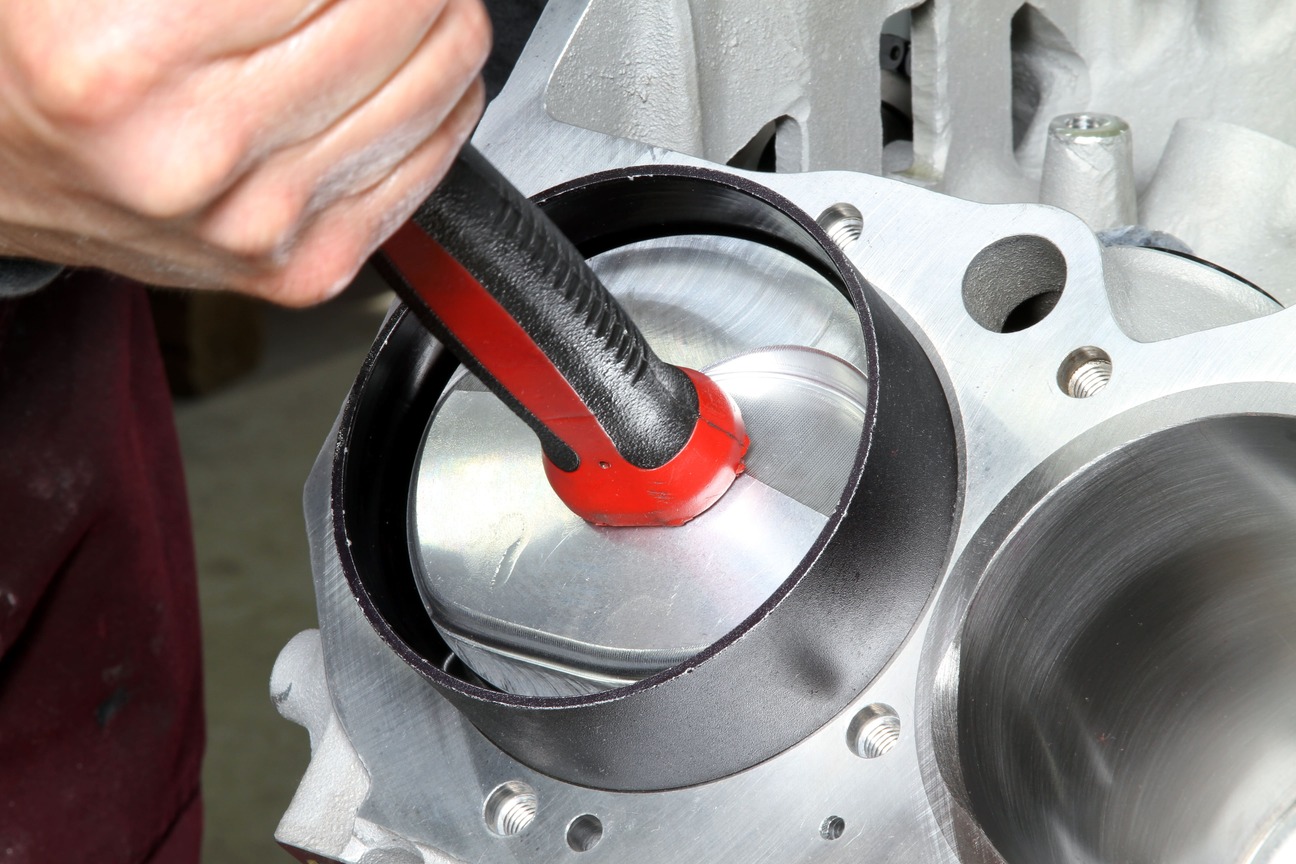

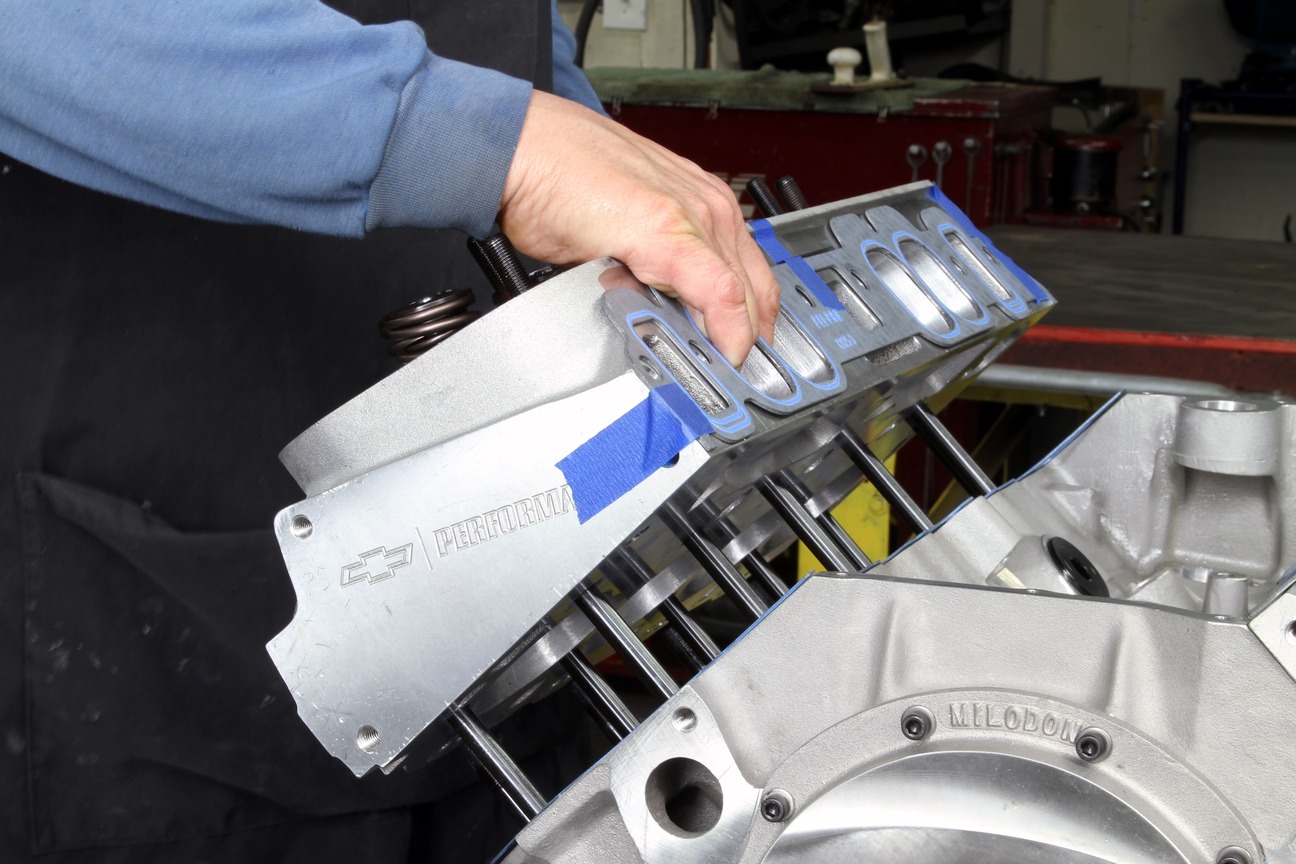

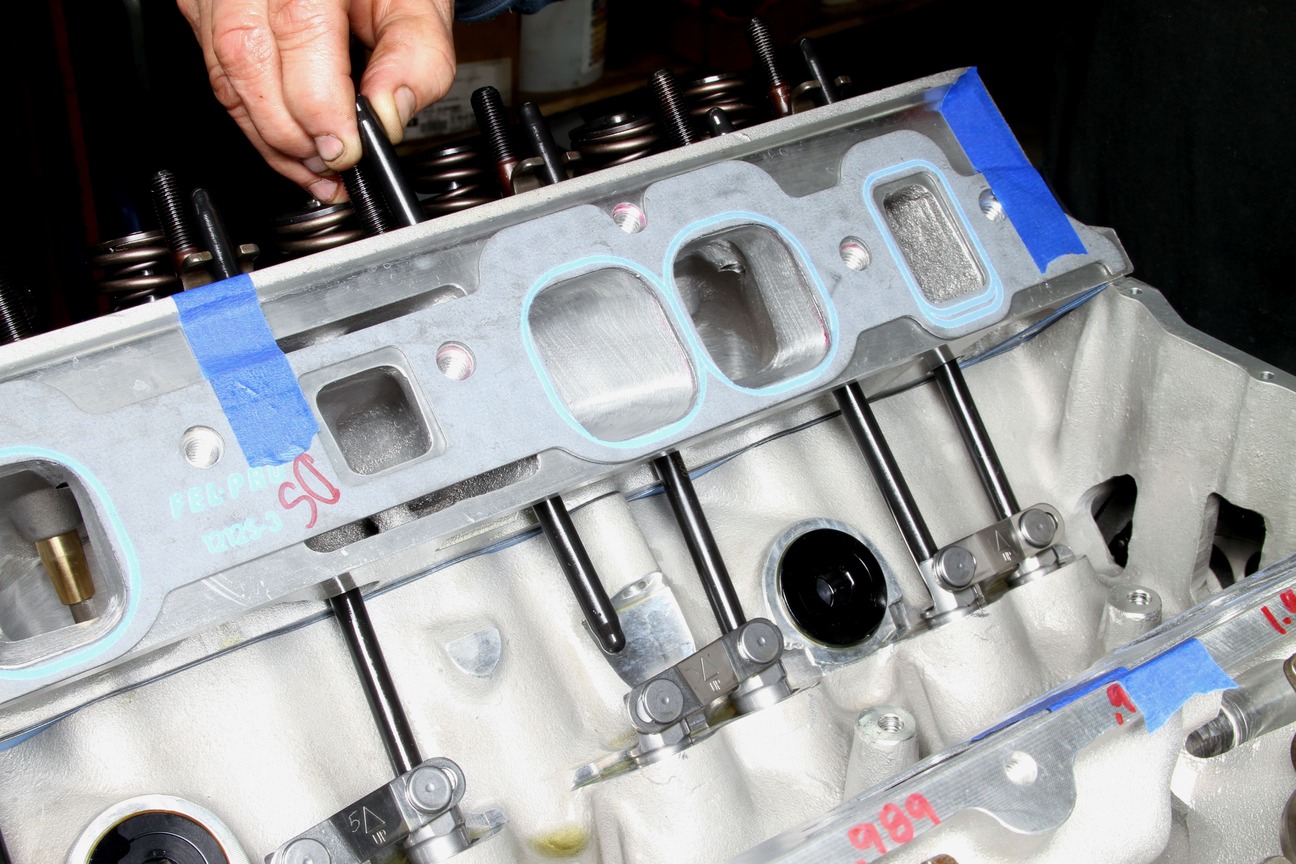

In Michigan, Valley Performance set out to build a contemporized ZL1 as a more streetable tribute that would accommodate modern pump gas. They started with a modern ZL1 block and oval port heads from Chevrolet Performance, but the goal of greater streetability would ultimately mean a lower compression ratio and a “smaller” camshaft than the original engine—parameters that would give builders Jack Barna and John Lohone a challenge.

“We dropped the compression ratio down to about 10.4:1 and used a cam that would produce good manifold vacuum for an engine that was going to spend almost all of its time on the street,” Barna says. “The original ZL1, of course, was really a racing engine. It wasn’t designed for cruising around town. We weren’t building a racing engine.”

To overcome the deficit induced by the lower compression, Barna and Lohone took the same course of action Chevrolet did, starting in 1970, when the company knew it was faced with looming compression ratio cuts to satisfy forthcoming federal emissions regulations and unleaded fuel: They increased displacement. Chevy upped the big-block’s inches from 427 to 454 and so did Valley Performance. Heck, Chevy even did it in the early ’00s with their Ram Jet ZL1 crate engine. It was really a 454.

Sacrilege? It depends on how you look at it—and when you look at it, you can’t discern the displacement, while Valley Performance’s solution was the most pragmatic for achieving the engine’s performance goals, without the benefit of high compression.

“No, it’s not a 427, but there was more to the ZL1 than the displacement,” Barna says. “It was the aluminum block and heads and we’ve got that, along with induction from a single Holley four-barrel carburetor. The cubic inches may vary, but the spirit is the same.”

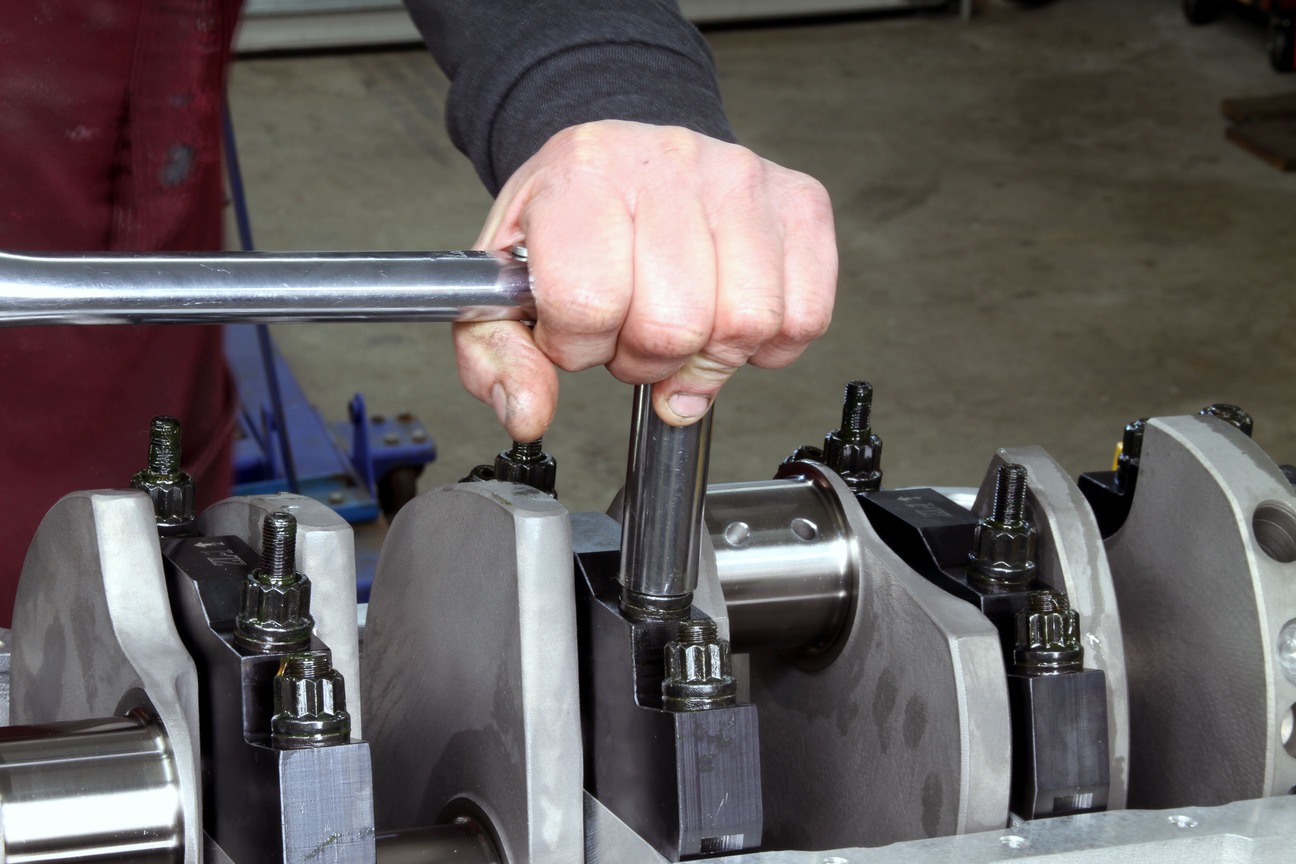

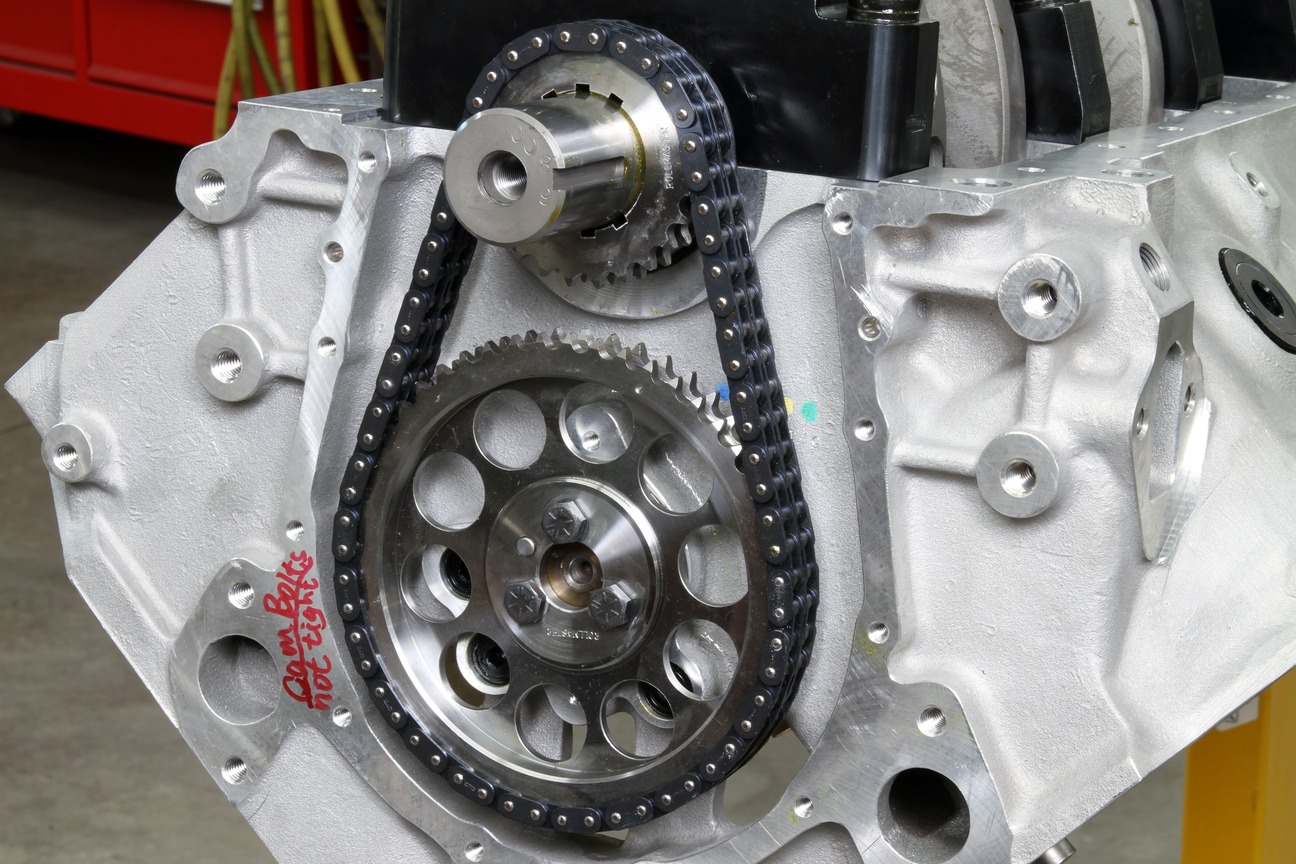

Another deviation from the original specs was the use of a hydraulic roller camshaft in place of the old-school mechanical flat-tappet design. Again, practicality won the argument, even at the expense of that unmistakably hostile, aggressive clatter of the solid lifters.

“To be honest, there’s not really much point in building a street engine today with a mechanical flat-tappet camshaft,” says engine builder John Lohone. “Even if you set aside the greater driveability aspects of a hydraulic roller, it’s much easier to wipe out a solid-lifter flat-tappet camshaft these days. The hydraulic roller is absolutely the way to go.”

350 Crate Install on a 79 C10: Check it out here

The project engine’s cam specs include 0.578/0.617-inch lift, which compares very closely to the original ZL1’s 0.560/0.600-inch lift, while the 230/234 degrees duration at 0.050-inch is a less than the original’s estimated 250 degrees at 0.050-inch. That means a less overlap than the original ZL1’s camshaft, which would enhance low-end power production in the project engine, particularly torque.

“Again, we were aiming for a strong street engine, first and foremost,” Lohone says. “The comparatively smaller camshaft was the just-right size for the rpm range at which this engine would spend most of its time.”

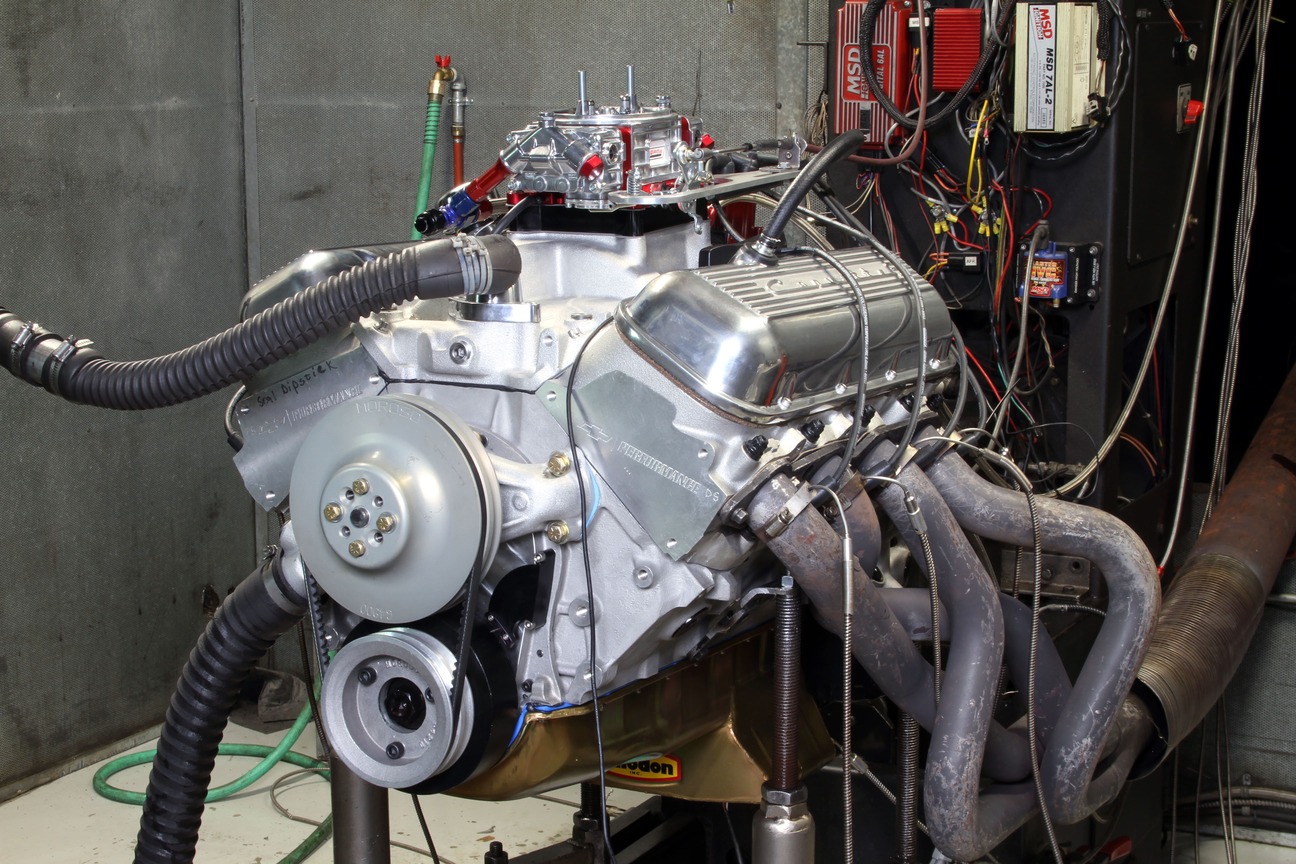

The dyno results, at Apex Competition Engines, confirmed as much. The engine made 500 lb-ft by 3,000 rpm and never dipped below that threshold until 5,500 rpm, peaking at 557 lb-ft at 4,700 rpm. As for horsepower, it matched the capability of the original ZL1, peaking at 527 hp at 5,100 rpm.

“The important takeaway from the results is this engine makes the same power as the original, but with a vastly more streetable demeanor,” Lohone says. “It’s a pump-gas engine that’s happy at low speeds and there is no need for periodic lash adjustments. Just fire it up and hit the road.”

So, a little less compression and a little less duration, paired with a few more cubic inches and a contemporary valvetrain delivers a street-friendly, modern tribute to one of the most legendary engines of the muscle car era. Those solid lifters will be missed, but it’s difficult to argue with the results achieved with Valley Performance’s formula. ACP

| ON THE DYNO | ||

| RPM | TORQUE | HORSEPOWER |

| 3,000 | 502 | 286 |

| 3,100 | 509 | 300 |

| 3,200 | 516 | 314 |

| 3,300 | 523 | 328 |

| 3,400 | 528 | 342 |

| 3,500 | 531 | 354 |

| 3,600 | 532 | 364 |

| 3,700 | 530 | 374 |

| 3,800 | 530 | 383 |

| 3,900 | 531 | 394 |

| 4,000 | 533 | 406 |

| 4,100 | 537 | 419 |

| 4,200 | 542 | 434 |

| 4,300 | 547 | 448 |

| 4,400 | 551 | 461 |

| 4,500 | 554 | 475 |

| 4,600 | 556 | 487 |

| 4,700 | 557 | 498 |

| 4,800 | 556 | 508 |

| 4,900 | 554 | 517 |

| 5,000 | 549 | 523 |

| 5,100 | 542 | 527 |

| 5,200 | 532 | 527 |

| 5,300 | 520 | 525 |

| 5,400 | 503 | 517 |

| 5,500 | 483 | 506 |

Peak numbers in bold.

SOURCES

Apex Competition Engines

(989) 248-5005

brandy2037.wixsite.com/apex

Automotive Racing Products

(800)826-3045

arp-bolts.com

Valley Performance

(616) 522-9710

valleyperformancellc.com