10 Smart Spending Strategies for Building Your Next LS Engine

By Barry Kluczyk – Photography by the Author

A few years ago, a colleague of ours spent more than a few bucks to elevate the performance of his LS1-powered fourth-gen Camaro SS. It was a bolt-on extravaganza, with long-tube headers, a snazzy-looking intake manifold upgrade, and a larger throttle body, along with a cold-air intake and more. The engine looked great under the hood and sounded even better through the headers.

On the chassis dyno and with proper tuning, power to the tires definitely increased, but the gain wasn’t dramatic. Worse, the car’s crisp street performance was dulled like your mom’s old caravan down a cylinder or two. To put it nicely, it was a dog, particularly at low rpm, where what little torque the LS1 made down there all but evaporated.

This Article Might be Helpful as well: Engine Wiring for LS Engine Swaps

It’s all because our buddy took the traditional bolt-on approach to building horsepower—the things we all grew up reading about when people were trying to coax an extra 25 hp out of a smog-laden two-barrel small-block. Opening up the restrictive intake and exhaust systems were the keys to make 275 hp back then, but it’s the total opposite with an LS engine.

A hotter cam is going to increase valvespring pressure, and the stock springs simply won’t be up to the task. When swapping the cam, match it with a corresponding spring upgrade. It’s a must.In fact, it’s downright detrimental in many cases, because airflow is already an LS’ advantage and the engineers did an excellent job balancing the intake airflow and exhaust to deliver a pretty optional package from the factory. Those traditional bolt-on moves, then, generally deliver less effectiveness for the money and often work against street driveability.

The key to building significant power in an LS and doing it more cost-effectively is to start on the inside with the camshaft and work your way out to the traditional bolt-ons. They’ll support and augment a cam upgrade, but they’re largely ineffectual without it. We’ve put together a list of 10 common and often necessary upgrades to build more power and support it.

Interested in Seeing More ACP: 427 LS Power That Looks Like Vintage 409 in 1961 Bubble Top Impala

We’ve listed them generally in order of importance, starting with the camshaft, but the keyword with all of them and your next LS build is strategy. In other words: Think before you spend.

You’ll be horsepower and dollars ahead in the long run.

A pushrod upgrade is another smart move when upgrading the cam, springs, and rockers. Hardened pushrods with thicker walls of at least 0.080 inch will provide the strength required for higher rpm capability and the resulting higher valvespring pressure.

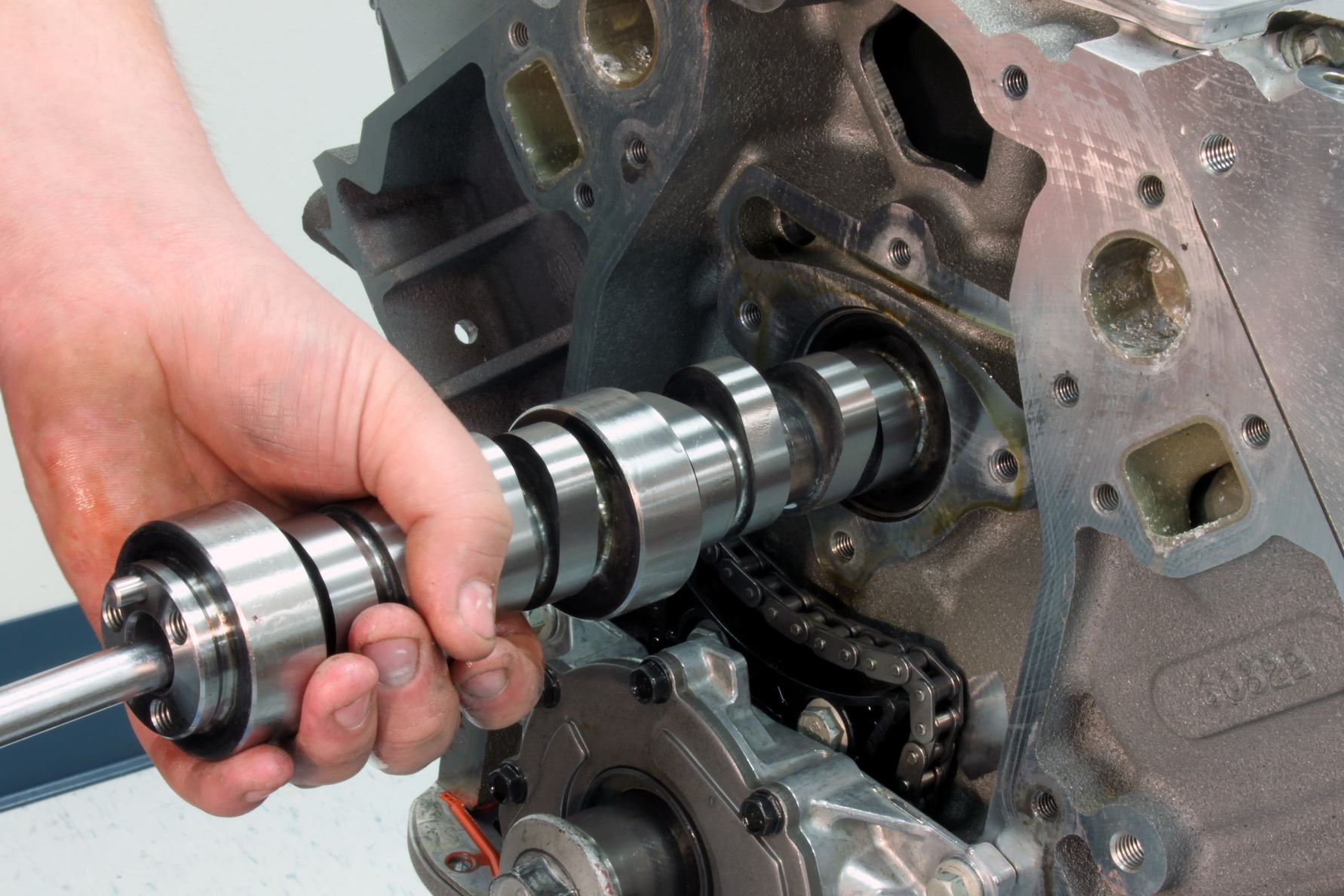

- Camshaft

If you do nothing else to your LS engine, cam it. Hands down, it’s the most cost-effective upgrade to be made to an otherwise-stock engine or one intended for additional performance upgrades. Believe us, it makes all the difference—like, upwards of 100 hp in some cases. Seriously. It’s all thanks to the cylinder heads, which crave airflow, whether the early cathedral port–style or later rectangular-port versions. The more air the better and that’s exactly what a bigger cam, with more than 0.500-inch lift and complementing longer duration will deliver. If there’s a downside to a cam swap, it’s that the greater horsepower typically comes at the expense of low-rpm torque—something that LS engines don’t have in abundance in the first place. But if you don’t mind giving up a few pound-feet for perhaps an extra 100 hp, cam your LS and don’t look back. Don’t forget the correspondingly upgraded valvesprings, either.

- Rocker Arms

There aren’t many weak points with an LS engine, but the factory rocker arms are one of them. The problem lies in the trunnion and complementing needle-style, low-friction, trunnion bearing. The trunnion can press on the bearing at high-rpm/high valvespring pressure, and when that happens, one or both sides of the bearing housing can be forced out and the needles will literally spill into the cylinder head. It’s not too much of a problem on a stock engine, but a camshaft-and-spring upgrade will typically bring the greater pressure on the rocker arm trunnions that will induce the bearing failure. There are aftermarket upgrade kits from Comp Cams that help prevent the problem, but it’s not a bad idea to replace the rocker arms altogether with stronger units when doing a cam-and-spring swap. It’s cheap insurance.

- Pushrods

While we’re talking about the valvetrain, it’s not a bad idea to upgrade the pushrods to complement an upgraded camshaft, springs, and rocker arms. The cam upgrade will enhance the engine’s rev capability and extend the rpm range, so you’ll want a correspondingly stronger set of pushrods to ensure the valvetrain’s strength, stability, and durability at those higher revs. The stock pushrods have 0.075-inch walls, so go with at least an 0.080-inch wall thickness on the replacement ones. You’ll be in a set for $150 or less. One more thing: It’s important to maintain the proper preload with the pushrods against the rocker arms. Decking the heads or using thicker head gaskets to gain a little compression will alter the valvetrain geometry enough that you’ll probably have to change the length of the pushrods, too. Take that into account when ordering them.

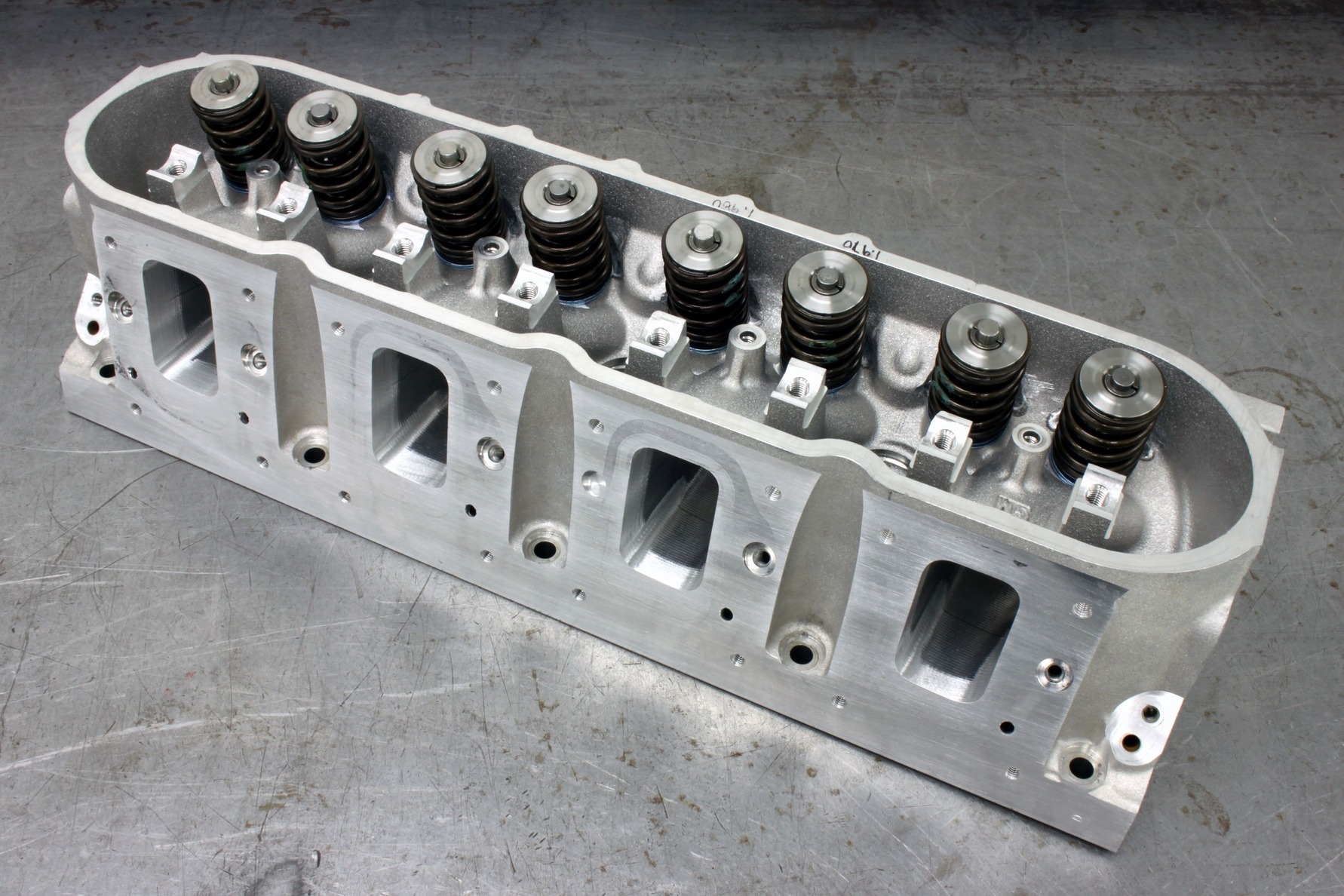

- Cylinder Heads

We’re getting into real money here, as a set of ported factory heads or aftermarket castings can start around $800 and grow to perhaps $1,500, or more. A higher-flowing set of heads is useless without the complementing camshaft upgrade, so you’ll have to factor in the expenses for the cam, lifters, and springs, as well as the rocker arm and pushrod upgrades discussed above. Even then, the power potential of aftermarket heads may not return the sort of real-world results, mostly because the factory heads are pretty good and often support the greater airflow delivered with a hotter cam. So, before keying in your credit card number for that set of heads, pull back and look at the bigger picture of your performance goals. If they include more time on the strip than street, then yes, a set of heads and the right complementing camshaft is the way to go. But if you’re running a street car that sees only one or two passes down the 1320 a year, you’re better off and money ahead to stick with only a camshaft/valvetrain upgrade.

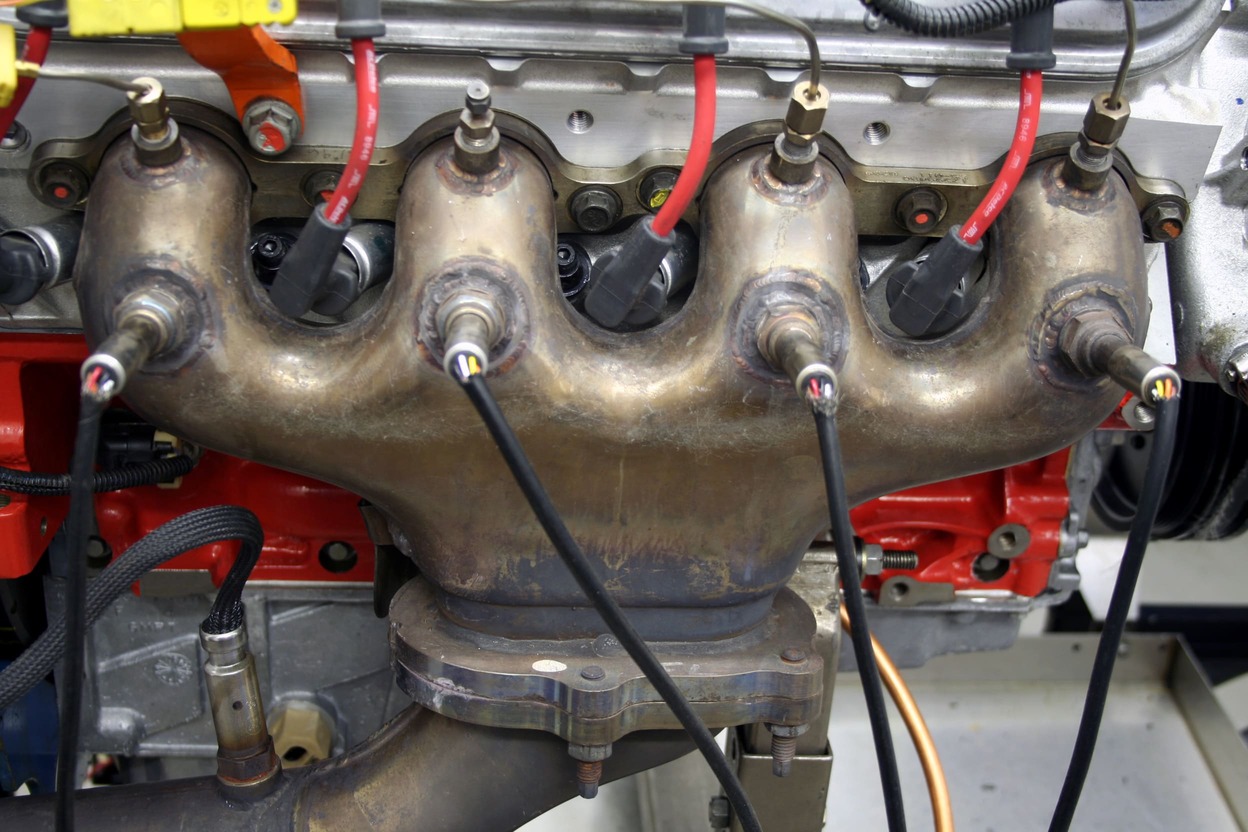

- Intake Manifold and Throttle Body

Yes, the boring black plastic factory intake manifolds leave a lot to be desired in the appearance department, but they’re not so bad in the airflow department. So, think long and hard before swapping a higher-flow manifold onto your LS. On a stock engine, it’s unnecessary and will provide only an incremental power bump, at best, at high rpm—while sacrificing low-rpm power and even driveability. The same goes for a big throttle body. In fact, even with a higher-flow intake manifold you probably don’t need to go nuts with a bigger-bore throttle body, unless you’re truly intending to spend most of the time on the strip. On a street car, it’s overkill. Invest in the manifold and throttle body only when you’re going for at least a cam-and-heads package. That way you’ll make the most of their capabilities.

- Fuel Injectors

You might get away with stock fuel injectors on an engine with a mild or moderate cam upgrade, but if you plan for more power, you’ll likely need to upsize the injectors, as well. Do it only when it’s necessary, based on project power increases, as like many of the items we’ve discussed in the story, too much can work against you with an LS engine. They’ll run you roughly $400-$500 a set, too. There’s a formula to follow for calculating injector size: Horsepower x 0.5 ÷ 8 ÷ 0.9. In the equation, horsepower is the projected horsepower of the engine, which is divided in half and divided again by the number of cylinders. After that, the number is divided by 0.9, or 90 percent of the injectors’ duty cycle. So, let’s take a naturally aspirated LS3 as an example. It’s rated at 430 hp and is fed by 42-pound injectors. We’re aiming for an even 500 hp with a moderate cam swap. Following the equation, 500 hp x 0.5 = 250, ÷ 8 = 31.25 and that ÷ 0.9 = 34.72, or a minimum of 34.7-pound injectors. That means with its stock set of 42-pound injectors, a larger set of injectors isn’t necessary. Also: If your horsepower calculation includes a supercharger, multiply by 0.6, and if it includes a turbo, multiply by 0.625.

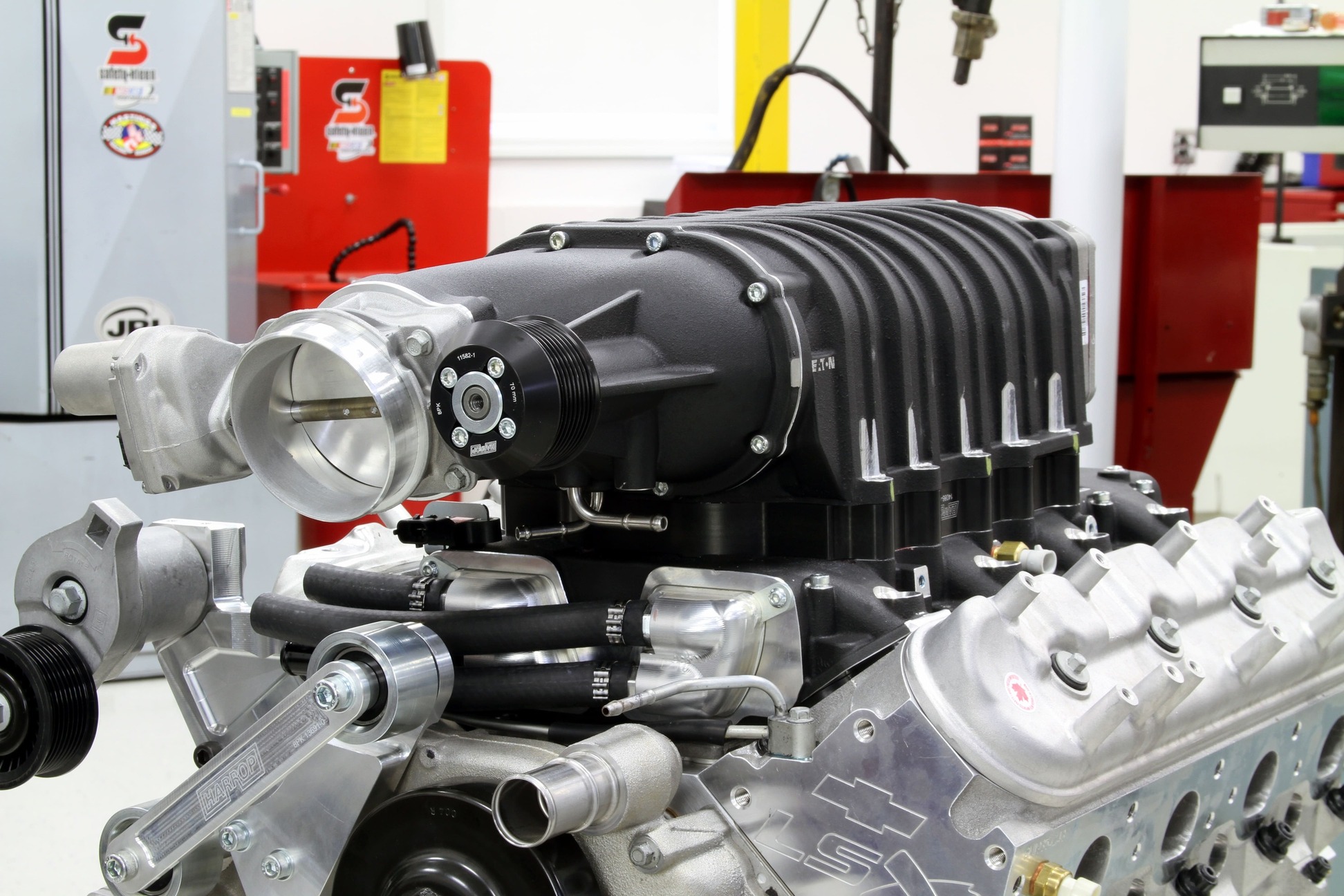

- Headers

Exhaust headers work well on a moderately or more aggressively built naturally aspirated LS engine that’s revving higher, but on a largely stock engine, the incremental power gain—if any—isn’t really worth the expense to purchase them and the time to install them. That’s because the factory exhaust manifolds are pretty good in the first place. Besides that, long-tube headers work best at higher rpm and will likely cost torque at the low end of the tachometer. The same goes for an engine with forced induction, but if you do install a supercharger, track down a set of LS7 exhaust manifolds. They flow like gangbusters.

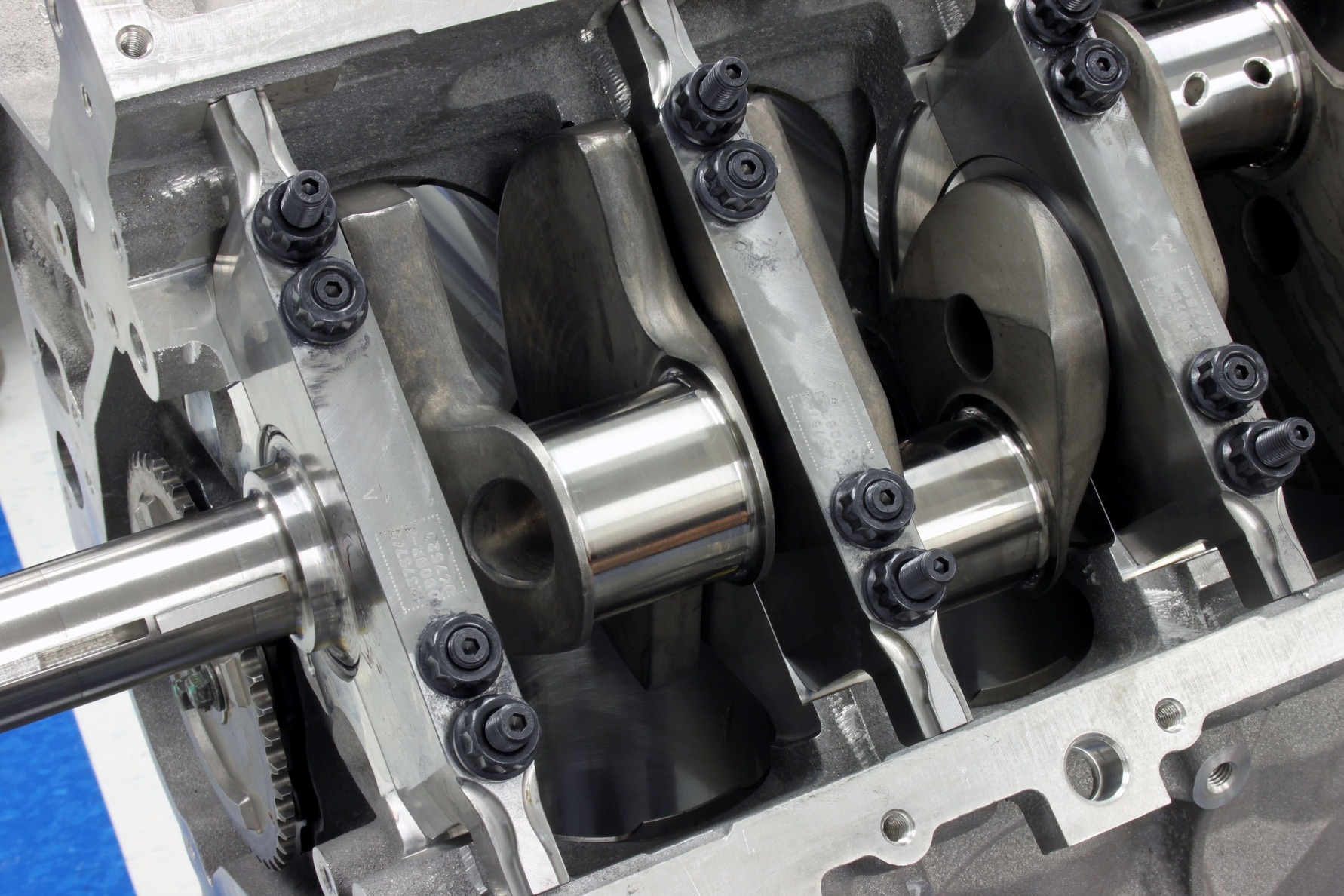

- Forged Rotating Assembly

Unless you’re going to pump more than about 8 pounds of boost into your LS engine, or more than a 100 shot of nitrous, you really don’t need to go through the time and expense of rebuilding the short-block with forged pistons or a forged crankshaft. The stock hypereutectic pistons and cast crankshaft are strong enough for just about all street and street/strip naturally aspirated combinations and lower-boost, bolt-on blower kits. But if you go as far as upgrading the rotating assembly, adding a mild stroker crankshaft can do wonders to further exploit the increased airflow capability of a hotter cam and heads.

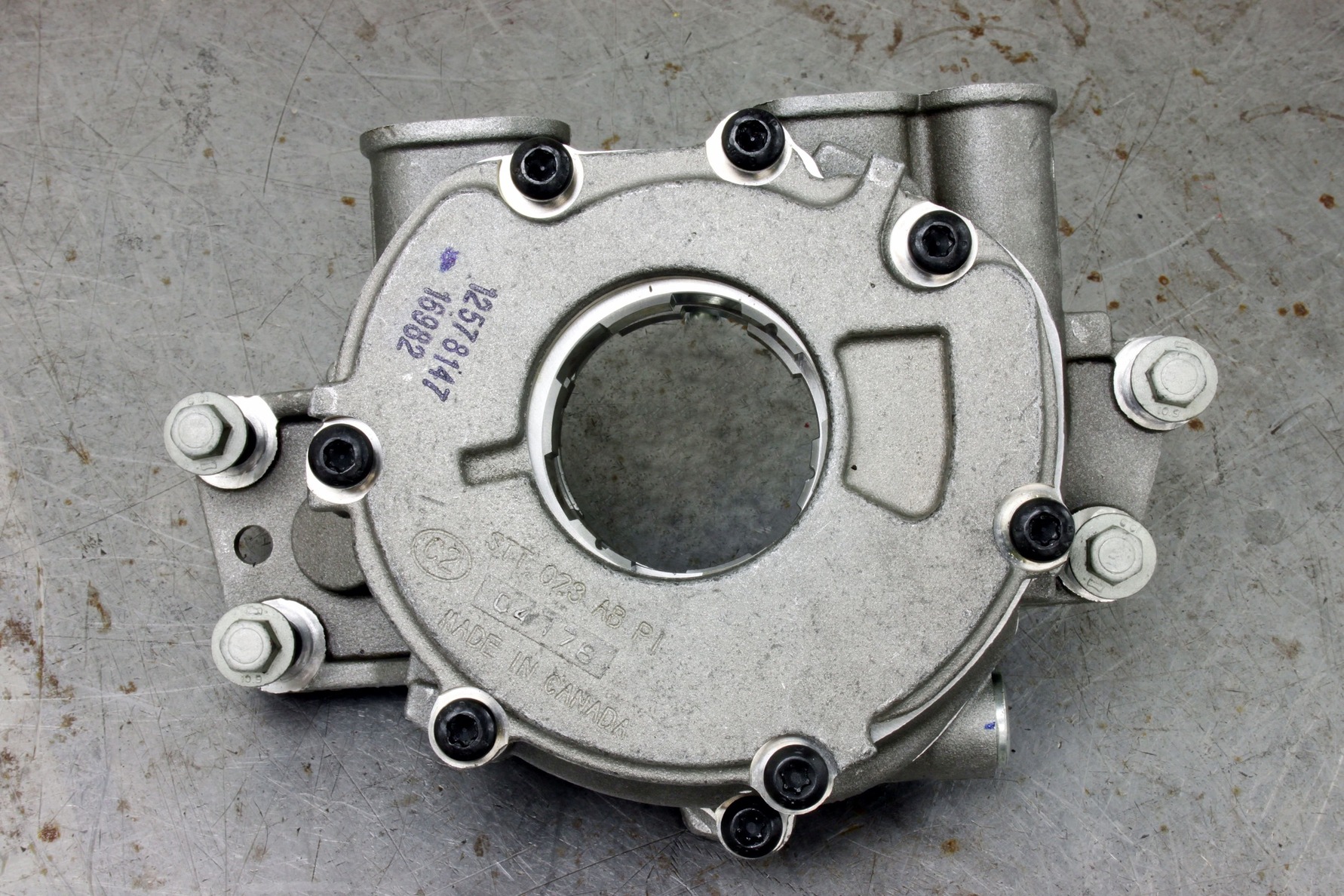

- Oil Pump

In stock or moderately built condition, the stock LS oil pump is generally sufficient, but with the increased rev capability delivered by many of the mods discussed in this story, its efficiency in delivering sufficient oil flow can deteriorate beyond about 6,000 rpm—a condition known as cavitation, which means the pump pulls as much oil as it’s trying to push. There have also been a number of documented oil pump O-ring failures with the stock pump. Stronger, higher-capacity wet-sump pumps are inexpensive, typically costing less than $200. It’s a smart investment, especially if you plan to ramp up the engine’s output in the future.

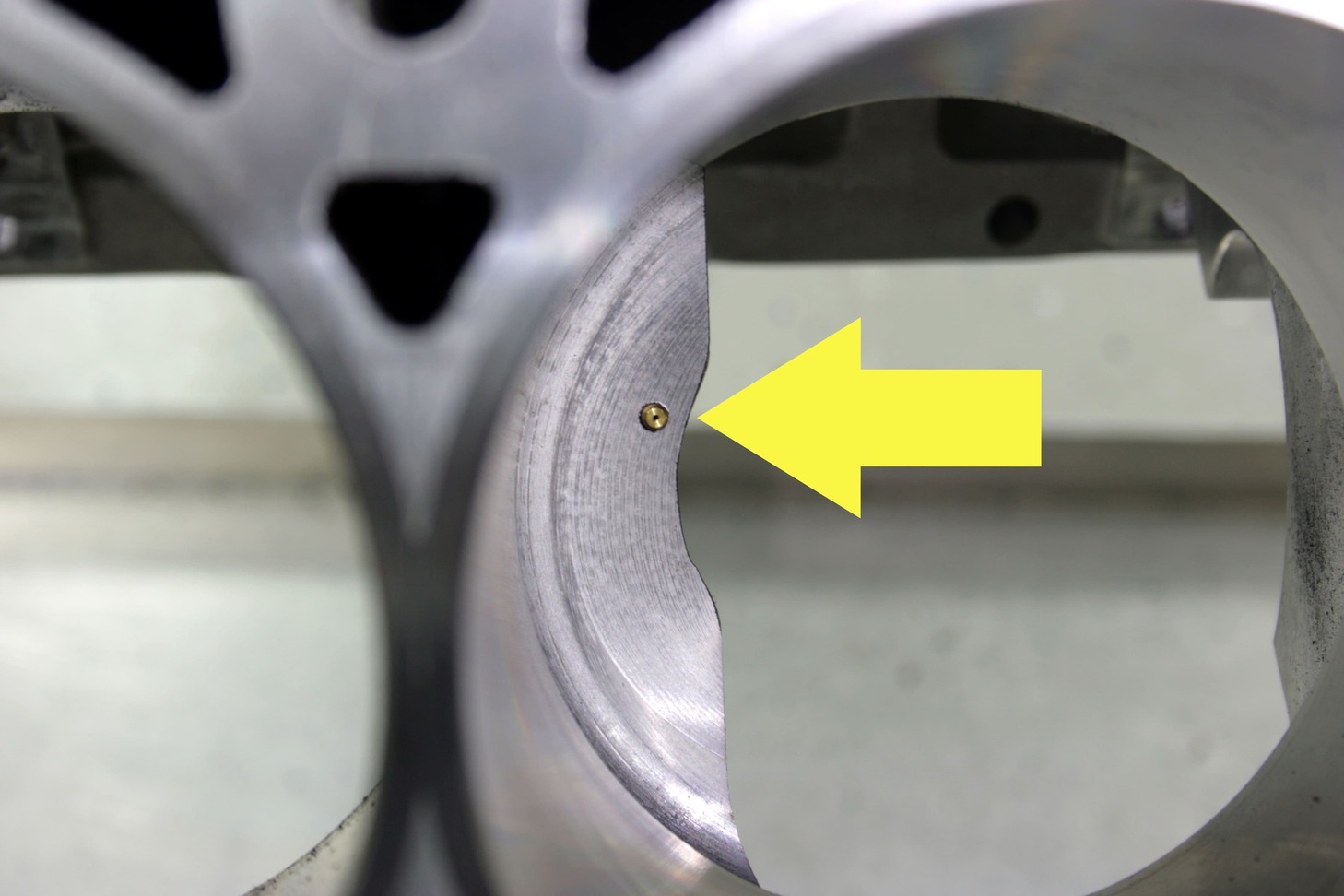

- Oil Squirters

If you’re performing a rebuild or a ground-up assembly of an LS engine, one of the smartest moves is installing piston-cooling oil jets, commonly known as oil squirters. They douse the bottom of the pistons with engine oil, which helps lower temperatures and ultimately enhances overall performance and durability. Installation is more involved than common bolt-ons or upgraded replacement parts, such as the lifters, but if you’re taking the engine to a significantly higher performance threshold—especially with forced induction—it’s highly recommended by the builders we know.