Uncovering the Mysteries of Single- and Double-Adjustable Shocks and Why You Need Them

By Jeff Smith – Photography by the Author and the Manufacturers

When the discussion lands on handling improvements for both older muscle cars and newer performance cars, the subject usually turns to shock absorbers. There’s a ton of information out there and it can be difficult to figure out the best approach to selecting the best shock absorber for your vehicle. This story offers a few easy-to-understand explanations concerning the differences between single- and double-adjustable shocks and what those benefits really accomplish.

It’s a challenge to approach this subject from both the entry-level ’60s muscle car side as well as from the impressive handling characteristics of newer cars like the Gen V Camaro. Frankly, a properly designed set of double-adjustable shocks on a new Camaro already blessed with big, sticky tires and a 21st century suspension would be an impressive addition that would deliver near-instantaneous improvements. Earlier muscle cars need much more help than just shocks.

If improved handling (we’ll touch on drag race applications later) with an older muscle car is the approach, it’s important to note that because these early suspensions could be described as fairly primitive. Adding a set of double-adjustable shocks to an otherwise-stock front suspension as the very first modification will improve the handling only slightly. What these cars need is a proper front suspension conversion that includes spindles, springs, tubular control arms, and a decent set of wheels and tires. Then a good set of double-adjustable shocks will be a much more noticeable improvement as tuning devices to generate ultimate handling and ride quality. This falls under the category of the integration if all the parts become far greater than their individual worth.

But to focus in on just the shocks, QA1, for example, offers one explanation on how to approach a shock absorber selection process. For simple highway use or boulevard cruising, a non-adjustable shock may work just fine. If your goal is improved handling on the street—a single-adjustable shock could do the job. For street/strip drag racing they recommend a single-adjustable “R”-type shock for the front while a more-aggressive drag racing or autocross/road course track day commitment would certainly benefit from a double-adjustable-style shock.

The issue with non-adjustable shocks is that there is one shot to achieve the desired quality. If the shock is too stiff or too soft or the ride isn’t what you expected, the only solution is to try again. With single- or double-adjustable shocks, you have the ability to tune them to your requirements.

As an example, almost everyone has a nearby highway that they regularly drive that attacks the car with a killer washboard. For us, it was a nearby freeway that bordered on making the passengers seasick with its wavelength-like hammering. It was so bad that for a while, GM used it as a test track for a bad road. Add a set of double-adjustable shocks, and with a little bit of compression and rebound tuning that hammering could probably be minimized if not eliminated. That alone would make the added expense of an adjustable shock worthwhile—especially if you drove that sketchy stretch of road every day.

Read More: Vintage Air’s Latest Front Runner for LS and LT1 Engines

Viking offers only double-adjustable shocks in its catalog but broadens this approach with four distinct lines of shocks. The Voyager line with its wider selection of adjustments within the normal range for street use will help dial in a comfortable ride. The next step up is the Warrior line intended for several different performance applications from Pro Touring to drag racing. The next step is pure competition uses with the Crusader line. Each of these lines of shocks will overlap slightly but with distinctly different forces in both compression and rebound.

We don’t have the space here to go through each shock company’s individual shock programs, but the message here should be that it’s important that you contact your shock company of choice to go over exactly how you will be using the vehicle. This will help them determine the correct shock and valving combination for your application. Of course, the more you know about how shocks work, the easier that selection process will become.

Let’s start by diving into some design definitions. When load is applied to push the shock shaft inward, this is called compression, bump, or sometimes jounce. When the suspension or shock shaft moves outward or expands in length, this is called rebound.

Shock absorbers should technically be called hydraulic dampeners. Their task is not to absorb shocks but rather to dampen the oscillations created when the spring is moving in either compression or rebound. All this dampening action converts movement into heat that finds its way into the hydraulic fluid that must be dissipated. And yes, we will continue the use of the conventional term shock absorber because it is so universal.

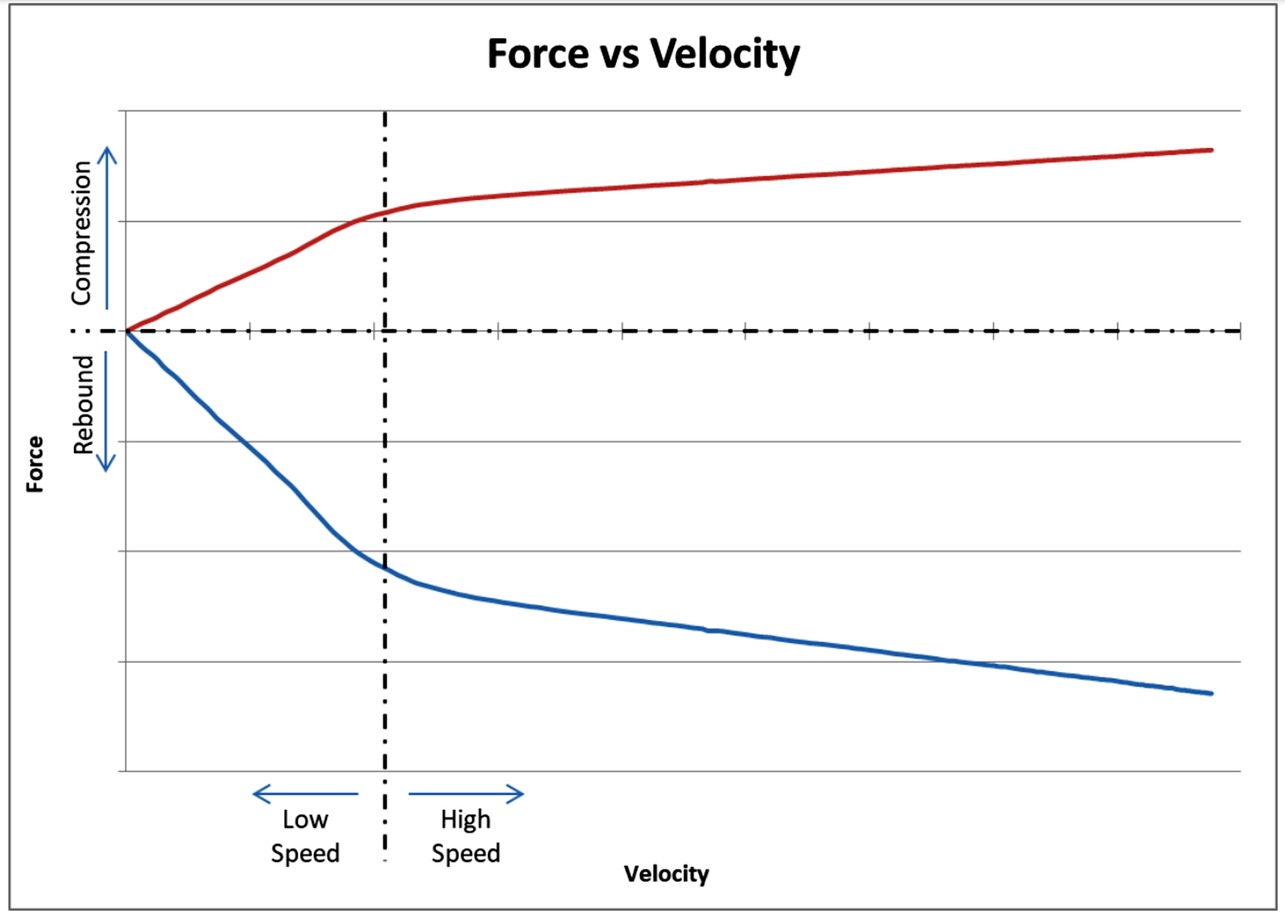

Shocks operate by managing shaft movement. This makes them velocity or speed dependent. No damping occurs when the shock is not moving. Shocks can be tuned to recognize and dampen for different speeds. These speeds are expressed as either low or high speed, again referencing the movement of the shock absorber shaft. A low speed could be body roll or pitch movements while high speed might be like hitting a deep pothole or a raised curb on a road course.

As mentioned earlier, all shocks fall into one of three categories: non-adjustable, single-adjustable, or double-adjustable. Within single-adjustable shocks, this adjustment is approached in different ways. Many single-adjustable shocks tune only in rebound, although there are a few that adjust solely in compression and there are a couple of companies where the single-adjustment changes both bump and rebound together. So, if you are considering a single-adjustable shock you should study these various adjustment characteristics very carefully.

Double-adjustable shocks are desirable because they allow the compression and rebound to be tuned independently. This is beneficial since situations can occur where, for example, the vehicle will require stiffening in compression but softening in rebound. That can only be accomplished with a double-adjustable shock.

Gaining in popularity are the triple and four-way or quad-adjustable shocks. For example, Viking produces both a Warrior and Crusader shock with three adjustments. The compression knob adjusts only low speeds. A small separate hex adjuster controls the high-speed compression valving while the rebound knob controls both high and low speed.

Viking’s Chris King tells us that these shocks are becoming very popular with both racers and high-end street enthusiasts who are looking for more control. King says, “I will almost always recommend a triple-adjustable because it offers more options.”

Check it out: We Improve Suspension Responsiveness and Adjustability With Bolt-On Coilovers From Aldan American

Four-way shocks take this one step further to provide adjustment of both high and low speed for both compression and rebound. These configurations are generally aimed at competition applications since they are priced commensurate with their adjustability. There is a trend now where many hard-core Pro Touring enthusiasts are embracing this technology, which again illustrates the trickle-down effect of race car development that eventually finds its way to the enthusiast.

All of these adjustable shocks are available in a vast array of valving options. These are often expressed as force ranges. These valving arrangements should be carefully considered. Higher force values (the “more is better” approach) are often not the best choice. As an example, Viking offers several valving choices within the Crusader line for both Pro Touring and drag racing. These valving options radically change the force values for both compression and rebound and it’s beyond the scope of this story to explain the various ways these can be used–or misused. That’s why it’s best to talk with a manufacturer about your specific application to get a proper recommendation for choosing not just the right shock but also its all-important valving option.

With this dizzying array of shock options in the market, one way to differentiate them is by descriptions of shock force curves. These curves are plotted on force graphs generated by shock dynos. These dynos generally plot their results using multiple lines that trace the force curves. These curves are revealed in pounds of force at a given shaft speed expressed in inches per second. As an example, a shock may exhibit 400 pounds of force in compression at 2 inches per second of shaft speed. This would be considered a high-speed portion of the curve.

With respect to adjustments, most shock companies will indicate the number of “clicks” or single step adjustments for that particular shock. These may change between shock lines and certainly between companies. Don’t be misled into thinking that just because one line of shocks offers more “clicks” that it is somehow superior or offers a greater range.

Now let’s shift our attention to the drag racing side of things since these applications demand completely different shock force curves and valving. Generally, front drag racing shocks focus on adjustability in rebound to either allow quicker front-end rise or to dampen this movement to fine-tune the 60-foot time. Rear drag racing shocks generally offer more control as double- or triple-adjustable in order to offer superior control over rear suspension movement. These shocks employ different force curves compared to other applications and again should be carefully chosen to properly match the car’s requirements.

An extremely critical point, especially for rear shocks on drag race cars is the position of the shock at ride height and whether the shock has sufficient length to accommodate the required suspension travel. What often happens is the shock tops out its travel during the launch, which will seriously upset the suspension and cause tire spin. Strange, with its focus on drag racing, offers a tremendous variety of shocks for various applications that can prevent this situation.

Strange offers a rear coilover conversion for GM A-bodies (as well as many other applications) that includes an adjustable mount that allows the user to position the shock to change the location of the compression and rebound positions in relation to the car’s ride height. While ride height can be adjusted with the coilover spring, this further adjustment allows setting the load in the spring independent of the ride height.

More reading: TURN THAT CRATE LS ENGINE INTO A VINTAGE WORK OF ART WITH LS CLASSIC SERIES BY LOKAR

This story has really only surfed the wave tops of an incredibly deep and complex area of suspension tuning but hopefully we’ve offered some glimpses into the different options available. A little bit of research diving into your own specific requirements can really pay off in terms of getting a firmer grip on traction.

QA1 Initial Adjustment Chart

| Front Shocks | Single Adj. Shocks | Double Adj. Rebound | Double Adj. Compression |

| Drag Racing | 0-6 Clicks | 12-18 Clicks | 0-6 Clicks |

| Nice Ride & Handling | 0-6 Clicks | 0-6 Clicks | 2-8 Clicks |

| Firm Ride & Handling | 6-12 Clicks | 6-12 Clicks | 8-14 Clicks |

| Aggressive Handling | 13-18 Clicks | 13+ Clicks | 14-18 Clicks |

| Rear Shocks | Single Adj. Shocks | Double Adj. Rebound | Double Adj. Compression |

| Drag Racing | 4-10 Clicks | 0-6 Clicks | 4-10 Clicks |

| Nice Ride & Handling | 0-6 Clicks | 0-6 Clicks | -8 Clicks |

| Firm Ride & Handling | 6-12 Clicks | 6-12 Clicks | 8-14 Clicks |

| Aggressive Handling | 13-18 Clicks | 13+ Clicks | 14-18 Clicks |

Sources

Aldan American

(310) 834-7478

aldanamerican.com

Bilstein

(800) 537-1085

bilstein.com

JRi Shocks

(704) 660-8346

jrishocks.com

QA1

(800) 721-7761

qa1.net

Strange Engineering

(847) 663-1701

strangeengineering.net

Viking Performance

(800) 236-6001

vi-king.com