Classic Ford With Modern L83 Chevy Power

By Ron Ceridono – Photography by the Author

By now everyone knows about how popular the General Motors LS family of engines has become for performance applications. Their potential for producing reliable, affordable horsepower is unmatched. But oddly enough, when these engines first came on the scene, some critics complained that GM was still using “old school” two-valve heads with a single cam in the block and pushrod valve trains. Many armchair engineers opined that technology dictated combustion chambers with lots of valves operated by multiple overhead cams were necessary for a modern performance engine. Suffice it to say they were wrong and the GM was right.

Read More: Rediscovered Passion: 5.0 Coyote Powered 1961 Ford F-100

While the LS series of engines did stick with a conventional valve train layout there was good reason for it. It makes for a much more compact V8 engine than an overhead camshaft arrangement (as even fans of the Coyote engine will have to agree). But just because the LS series has pushrods doesn’t mean it’s not loaded with modern technology. The deep-skirted LS block with cross-bolted main bearing caps makes for a stout lower end, the pistons are hypereutectic with thin “metric” rings for reduced friction, the camshaft has been raised compared to its small-block predecessors to allow for not only a larger-diameter cam and bearings but a larger-diameter crankshaft as well, and the list goes on. But arguably the real technological advance of these engines can be found in the heads. The 15-degree valve angles allow for superior airflow, the ports are evenly spaced and symmetrical (as opposed to the Gen I and II Chevy small blocks with the center exhaust valves and ports next to each other). The rocker arms are still stud mounted, but this time around the ratio has been increased from 1.46:1 to 1.7:1, a rocker arm cradle has been added, and beehive springs are used. There’s all that and lots more to make the LS lovable, but GM hasn’t been resting on its technological laurels and the next advancement in design is direct fuel injection.

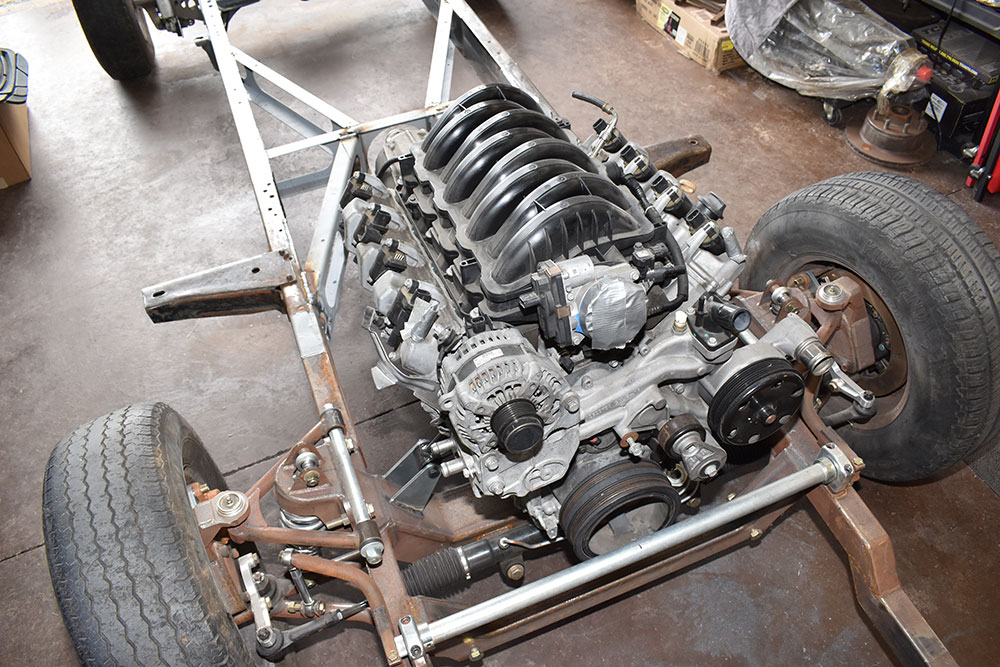

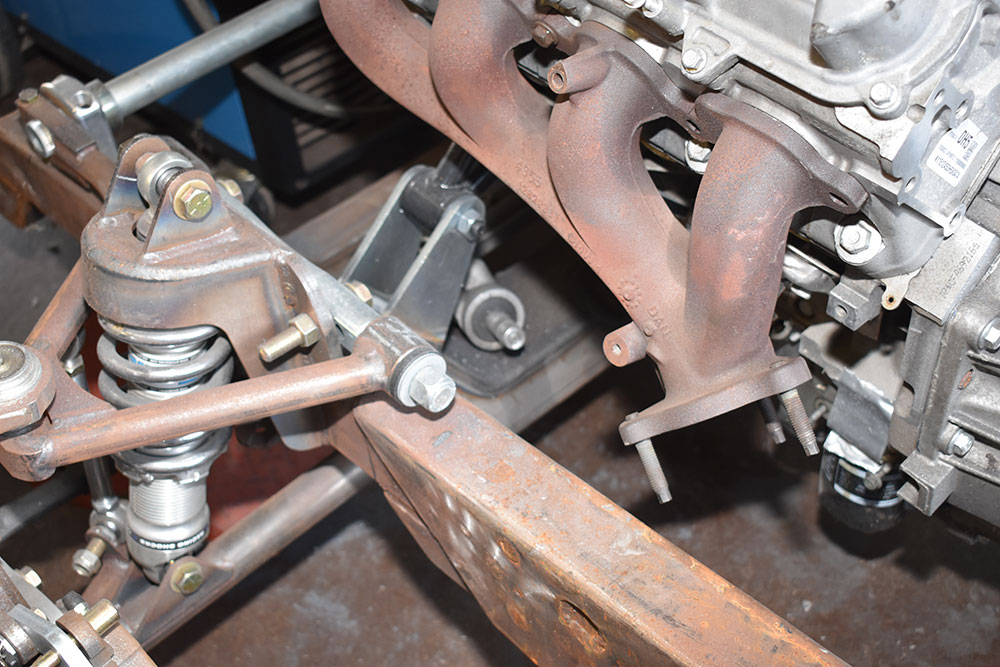

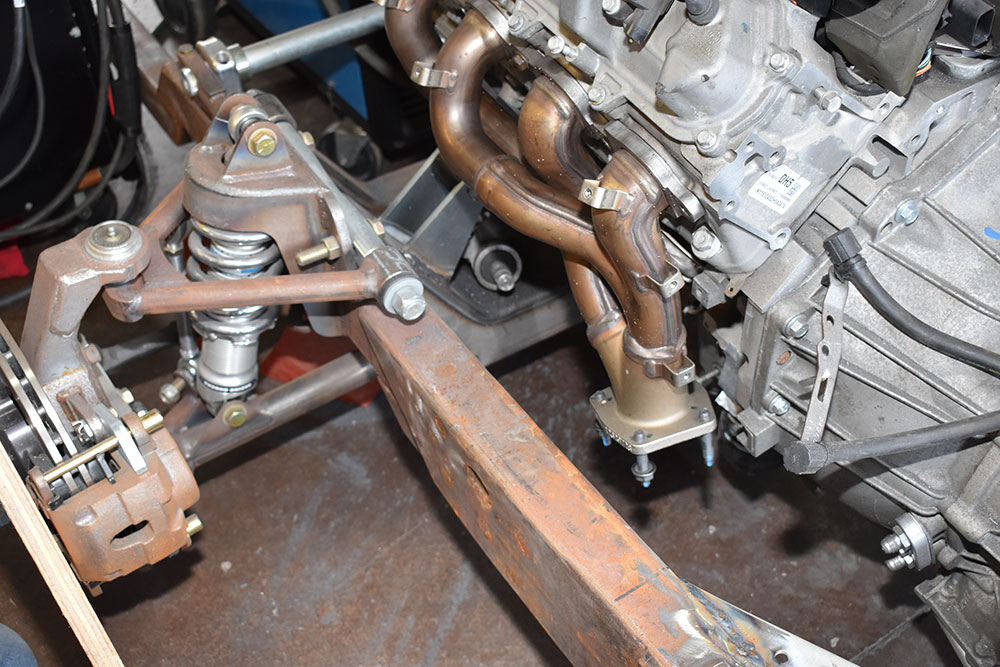

Recently our friend and fellow classic truck aficionado, Paul Willis, decided to build a ’55 Ford F100 that would be sophisticated enough to replace his ’15 Chevrolet Silverado as an everyday driver. We’ve followed along in CTP as the Ford’s original frame was equipped with a Speedway Motors G-Comp front suspension clip up front and a C4 Corvette Independent Rear Suspension in back by way of a Flat Out Engineering installation kit (see CTP July ’21 issue). Obviously the chassis was going to make for a great driver, so when Willis went looking for an equally user-friendly engine for this new project the first thought was an LS engine. But then for a truly sophisticated, everyday ride he thought, why not go for the latest technology, a Gen V LT direct fuel injection L83 engine like the one under the hood of his current pickup.

Rather than deliver fuel to the intake tract outside the intake valve, like throttle body and multi-port systems, direct injection introduces fuel into the cylinder. The advantages of this are many—increased fuel economy, better power, and lower emissions. Of course to inject fuel directly into the cylinders requires a high-pressure delivery system, consequently these engines have a high pressure pump at the back of the block that is under the intake manifold and driven by the camshaft. Pressure from this pump can exceed 2,000 psi, which is necessary to overcome the pressure in the cylinders on the compression stroke. To find out more about the Gen V direct-injected engines, check out Ryan Manson’s excellent article, “Everything You Want To Know About The GM Gen V LT1 Engine” in the June ’22 issue of CTP. For our purposes here we’re concentrating on the differences between an LS and a Gen V LT engine in terms of installation in a classic truck.

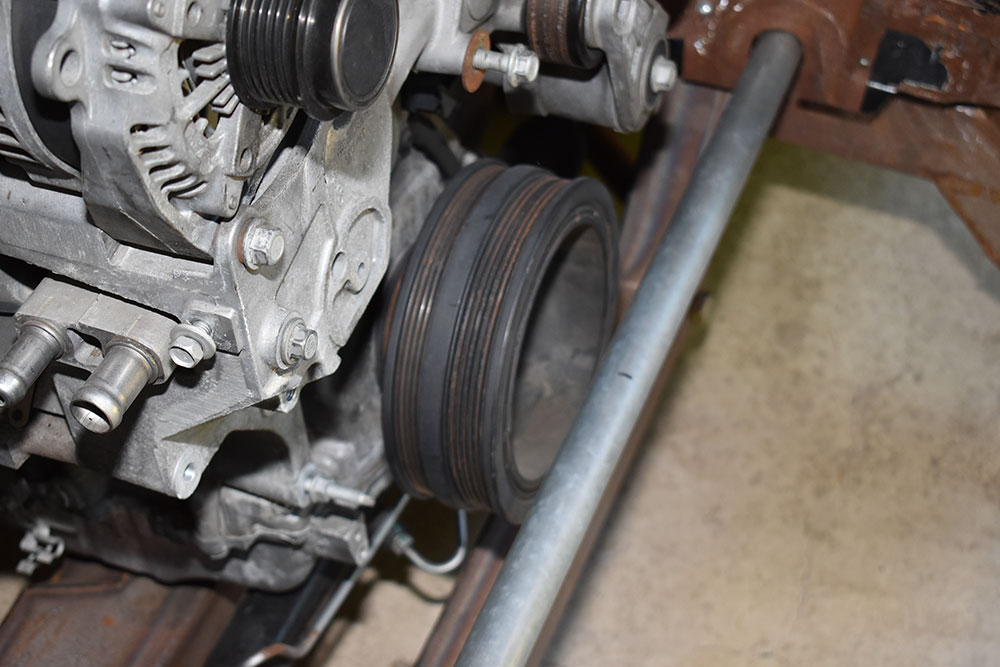

Some of the most obvious differences in the Gen V and earlier engines are the location of the water pump and as a result the configuration of the front drive system. There’s no power steering pump thanks to the electric power steering that GM is now using. Some of the more subtle differences between the Gen V engines and the earlier LS engines are the location and spacing of the engine mount bosses on the block, the oil pans are different and won’t interchange nor will the exhaust manifolds due to the Gen V’s unique bolt spacing, and the bellhousing bolt patterns are different. The top transmission attachment point has been rotated to the passenger side of the block due to the location of the high-pressure fuel pump at the back of the block above the camshaft. Something that will look familiar is the thermostat housing in the engine’s upper radiator hose outlet (even though the thermostat housing is plastic).

Read More: “Rusty Ripper” The Supercharged 5.0 Coyote Powered F100

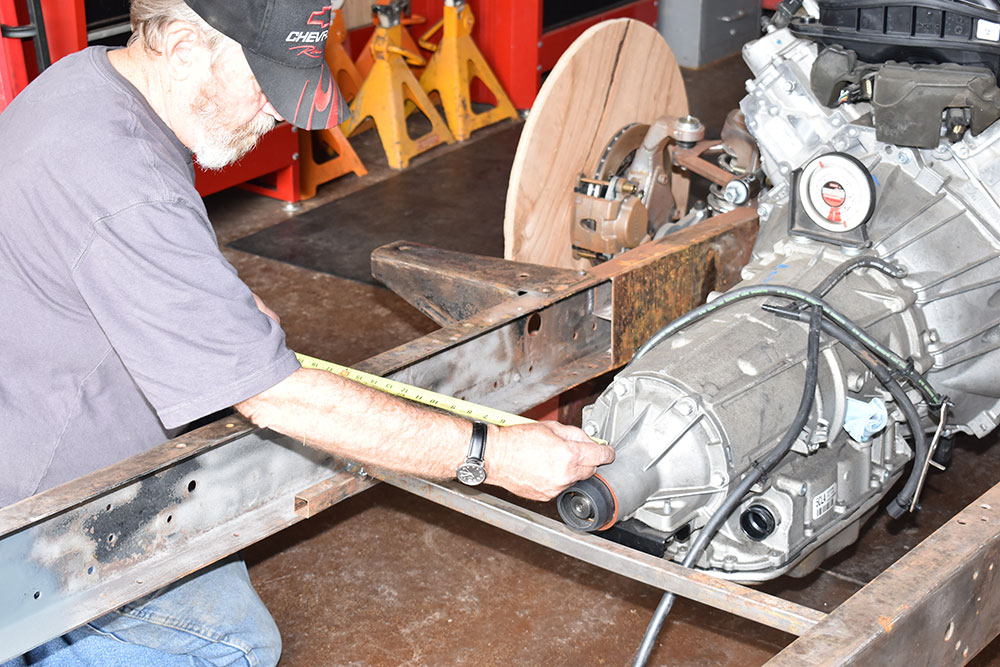

The contemporary Chevy engine that will take place under this Ford’s vintage hood is an L83, all-aluminum, direct-injected 5.3L (325 ci) from a ’15 Chevy Tahoe. This engine has 11.0:1 compression and is rated at 355 hp at 5,600 rpm with torque of 383 lb-ft at 4,100 rpm. While there are combinations that will produce more horsepower, this truck is being built as an everyday driver so the engine will remain stock. Backing up the V8 engine is a 6L80E transmission with a double overdrive, a gear ratio spread of 4.03, 2.36, 1.53, 1.15, 0.85, and 0.67, and a lockup torque converter.

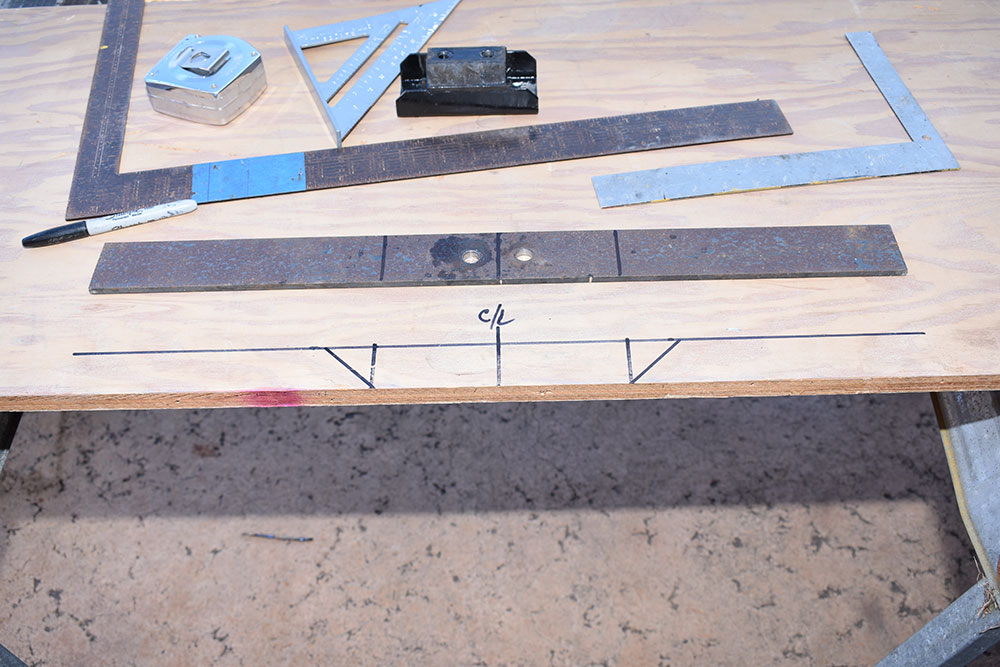

While the engine and transmission going in this truck are state of the art, we opted for an old-school approach to provide a transmission mount and add some torsional rigidity to the frame by installing an X-member similar to those found under early Fords. We used a universal Super X crossmember kit from Dagel’s Street Rods (541-378-4434) that included a center crossmember and four X-member legs (kits are also available with two if used as a K-member). The individual components are made from 11-gauge steel that measure 5 3/4 inches deep with 1 ¾-inch flanges. To support the automatic transmission we fabricated a mount from ¼x2-inch steel strap and bolted it to the bottom legs of the X-member.

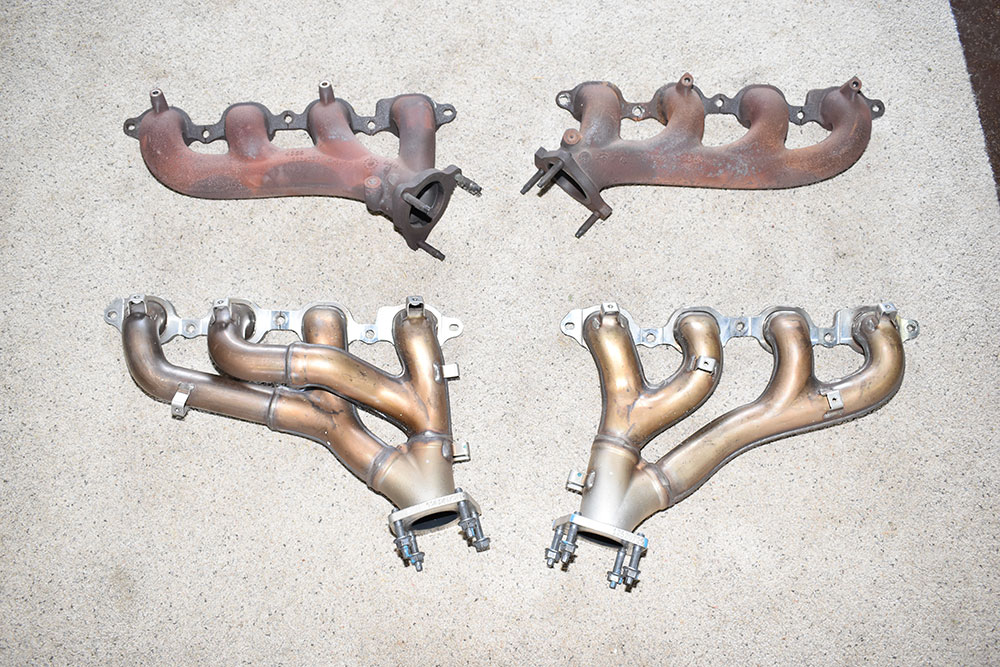

When doing any engine swap there are a number of things to consider to prevent problems later on—providing sufficient room for a radiator and fan along with the clearance next to the exhaust to route a steering shaft from the column to the steering gear wherever those components may be. In this case room for the cooling components wasn’t a problem as the engine is set back in the chassis to fit behind the anti roll bar and move a little weight onto the rear wheels. However, the stock Tahoe exhaust manifolds were bulky enough to make routing the steering shaft difficult. The answer to that problem came in the form of a set of factory headers off a ’20 Camaro with 6.2L engine.

Read More: A Coyote-Swapped First Gen Ford F100, That Took a Lifetime to Build

With the engine and transmission in place there are a few things left to sort out, such as mounting a pump for the power rack-and-pinion and a compressor for the AC system. Of course making all the electronics required to make the engine and transmission function will be a story in itself. But all that is for another time, so stick around, there’s lots more to come.

Source

Speedway Motors

(800) 979-0122

speedwaymotors.com